|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| News & Features |

|

The agony and the ecstasy of losing and winning |

|

solicited and edited by Bob Alman layout by Reuben Edwards Posted July 24, 2014

|

Stories of victory and defeat are virtually inevitable over drinks at the bar. We most love to tell stories, of course, of beating someone we "shouldn't" have defeated because of their championship celebrity. But the shocking losses--sometimes due to our own or our partner's over-confidence or stupidity--are even more unforgettable, relived often in the middle of sleepless nights. Sometimes there are lessons to be learned (such as "You haven't won until both balls are pegged out") and vows to be uttered (including "Don't shoot anywhere near the peg or a hoop on your last shot in the rotation at the end of a timed game you think you've won.") Most of the players I asked for a story supplied one, but one highly ranked fellow told me, "Telling a story about an unexpected win sounds boastful to me, and describing a loss is usually sour grapes." Some players drew lessons from their experience, but mainly the stories in this discursive article merely show that croquet is, after all, a sport: Somehow or other, either player can emerge from a game as a winner, given a sporting chance.

First, some definitions on courts that are Easy, Difficult, or Bad

Whatever the circumstances, we always win or lose on a particular court. In seeking insightful generalizations from the solicited anecdotes, I have found it useful to keep these distinctions in mind:

|

| "We called it Croquet Heaven when it was built and loved to play there, and in the early eighties the courts were regarded as among the "easiest" in the world--so easy that Robert Fulford confidently tried sextuples in nearly every game of the Sonoma-Cutrer World Championship. The lawns and the hoop settings used in the contemporary Sonoma-Cutrer Invitational are more difficult." |

A BAD court is one that nobody cannot play perfectly because of long grass, uneven texture (mixture of thick grass and no grass) and hills and swales. By denying the strong player the benefit of his skill, it gives the weaker player a sporting chance of winning, although there will doubtless be a lot of interaction.

An EASY court is not very fast, it is evenly textured, and set with easy hoops. It will minimize interaction, again making it possible for the weaker player to win with a good run of luck.

A DIFFICULT court is also evenly textured, but hard and fast as well, requiring skill, delicacy, and precision in playing breaks, and set with tight hoops. There will be a lot of interaction, so a DIFFICULT court probably provides the best chance of winning to the highly ranked and proven expert.

|

| This Paddy Chapman photo shows the specially designed Atkins Quadway hoop set into the hard and fast court of United Croquet Club in Christchurch for the 2014 MacRobertson Shield. The event was engineered to produce maximum interaction of the players from rejected hoop shots and failed breaks, thus helping to ensure that the best team would win. |

|

| Paddy Chapman practices a close-in hoop stroke before the 2014 MacRobertson Shield on United Croquet Club's lawn five. His New Zealand team won the event. |

Most of us play most of our events and pick-up games on courts that are somewhere between these extremes. Within a fairly narrow margin of grades (say, 400 points) or ranking positions (say, 50 or 60) we will try to beat the odds, and sometime we succeed. And thus we generate a story for the bar that we may enjoy telling without embarrassment, after a few drinks.

|

JAMES HAWKINS--Learning a lesson in victory

I played Stephen Mulliner in the Men's Championship at Cheltenham in 1998. I'd had an indifferent week, and scraped through to the quarterfinals; he was Number 2 seed and was playing well. We met on Lawn 8 in front of the clubhouse on Friday afternoon, just as spectators gathered for tea. I hit my long shot, and had the chance of scoring. What pressed me on was not the prospect of a win, but the need to avoid the embarrassment of dismal failure. I got a ball round, Stephen hit and finished the game, but I'd achieved my goal of not disgracing myself. Job done, and the more I relaxed the better I played in the next two games. I equalised, and we went to the decider. Mulliner blinked first, clattering a hampered shot to let me in. My win was unexpected for both of us.

I freed myself from obsessing over ranking positions and the weekly grind of the championship circuit. It's nice to win matches, but I'll never wear a Great Britain shirt, and I won't win the World Championship. I'm happier for having taught myself that lesson. |

|

ERIC SAWYER--The upset is a mirage

According to the World Croquet Federation, my biggest upset win in Association Croquet was over Jeff Soo in December 2013 during the US Open. The WCF views that as my biggest upset because there was the largest disparity of grades between myself and the higher graded player I beat. Who am I to argue with the WCF? But the interesting thing with that game was that it really wasn't a match between two opposing foes on the same playing field. Alright, technically it was, but when I look back at it now in hindsight, it was like two different games. It was the opening game of the US Open, and Jeff looked really rusty. He was swinging hard and hitting hard, but he was missing ... a lot. On the other hand, I was having a steady, solid, unspectacular game. Nothing impressive, nothing bad. So when Jeff went for a big shot and missed, I kept getting ready-made breaks easy to run.

On the one hand, it was nice beating somebody like Jeff. On the other hand, the win wasn't terribly satisfying. I didn't get the real Jeff Soo that day. As Jeff says, "Any stiff can beat me; the key is did you impress me?" I certainly didn't impress anybody the day I beat Jeff. For a while, I toyed with the thought that I was just being too hard on myself. But that thought completely vanished in April of 2014 when Jeff beat the snot out of me during the US AC Nationals. On that day, I played the real Jeff Soo. Upsets are a bit like a mirage. They are illusive and alluring. When you finally snag one, they disappear into the swirl of reality. Enjoy them while you can. But don't delude yourself.

|

|

JEFF SOO--Seeking victory in balance

Eric's win doesn't even make my top ten list of biggest upset losses. Play the game for a while and one will get one's share of upsets, both wins and losses. This is a result of two things: the normal distribution of random events, and croquet's relative lack of interactivity. That is, luck matters quite a lot in croquet, especially at the championship level where there are fewer turnovers. This "giant-killing" potential is a big part of croquet's appeal for rank-and-file players. This is why the Kiwis made sure to create such difficult playing conditions at the 2014 MacRobertson Shield. Difficult conditions = more turnovers = fewer upsets.

|

|

REG BAMFORD--When you couldn't possibly lose...

I was partnering Tony Le Moignan in the British Open Doubles. He was highly-ranked in those days (around 2006-8). We had high hopes of winning the event. We had what I'd call routine opponents--a bit harsh on Leo McBride, but he was one of them. We had won the first game comfortably, and Tony was completing a Triple in the second to win +26TP. He'd done all three peels and had a two foot peg-out to win. I turned to one of my opponents, who was chatting with me, and we shook hands. "Good luck in the next round", he said to me.

I looked up to see Tony walking towards me, looking rather ashen-faced. "I missed the peg-out", he said. Indeed he had. His croquet shot had pegged me out, but he had played a fresh air shot with his own ball. I sat next to Tony in silence for most of the next game. The opposing team took a ball round to the peg. Tony shot and missed. They finished. The inevitable happened in the decider--we didn't take croquet, they won +26, and we had been knocked out. Ouch!

|

|

CHRIS CLARKE--Playing the odds

My comments should give an insight into how I think about all sporting contests. I've had a look on the ranking list at my 10 "biggest upset losses."

Year Diff Opponent Grade Opp Grade 1 1994 836 Ed Duckworth 2627 1791 2 2007 821 Stuart Bullen 2608 1787 3 2004 624 Paul Salisbury 2496 1872 4 2007 624 Andy Davies 2629 2006 5 1994 567 Brian Hallam 2604 2037 6 1989 561 Lewis Palmer 2418 1858 7 1996 535 Alex Leggate 2535 2000 8 1996 526 James Hawkins 2536 2011 9 1992 522 Gail Curry 2575 2053 10 2008 517 Phil Cordingley 2655 2138 I have to say that I don't think I learned anything from any of these losses; they all had perfectly reasonable explanations that are just part of sporting contests; nor did I learn anything from the equivalent table of my ten biggest upset victories. If you play for long enough, you are bound to lose the odd game. In some of the cases above it was a matter of my opponent playing a very good game against me, in others, I was playing poorly at that particular time, for a variety of reasons. I am often told that my ability to distance myself from the outcome is unusual. I believe I have become better at this over the last 12 years, thanks to my line of work (sports betting). In sports betting, you need to be able to detach yourself from emotions and simply view each position from a mathematical standpoint. Try not to worry about whether you win or lose. Instead, concentrate on... a. Choosing the correct line of play before each stroke b. Executing it to the best of your ability

|

|

BOB ALMAN--winning through sheer ignorance

In the mid-eighties, the Arizona Open was a one-flight tournament and the first major American Rules event I entered. Believe it not, I did not know how to play breaks, virtually unknown in San Francisco at the time. But I did know how to set a rush of partner ball on the boundary for the next hoop, and score it. So that's what I did, throughout my game with Richard Pearman, the multiple national champion of the time, in our early morning game on the 3/4 size Patmor court, which was icy and had sloping boundaries. Pearman played correctly, attacking me on the boundary at the earliest possible time. However, he knocked my ball over the 9-inch margin. So I ignored his ball, set my rush with my partner ball, croqueted to hoop position, scored the hoop, and shot out of bounds to set another sideline rush for the next hoop. Surprised but undaunted, Pearman tried an attack with the other ball, and the same thing happened. He was partner dead, which allowed me to go all around the court with relative impunity on the 3/4 court. Whenever I felt endangered, I just switched to the other ball with the same sideline rush/croquet/clear combination of strokes.

|

More stories and an editorial summation

Most of my undeserved victories came as a result of a SHORT format. American Rules End Game Duplicate is my favorite one. The late Jerry Stark and I figured out this format and charted numerous End Games precisely with court positions and deadness. All the competitors played exactly the same situation. Most of the games lasted just a few rotations.

|

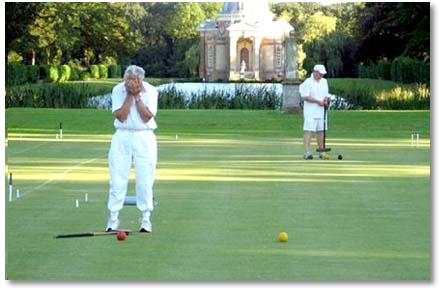

| This John Beverington snapshot from 2007 eloquently reveals Tom Anderson's agony and the potential terrible consequences of missing a short roquet. We all do it. |

In this particularly memorable one, I had a chance to try a long peg-out of one of Jerry's balls and it succeeded. l won the game and the entire event. It was a SHORT FORM triumph.

The other SHORT FORM triumph was in Golf Croquet and also with Jerry Stark as the opponent. Jaguar was his sponsor at Meadowood, more than an hour's drive north, so the publicity for his prize-money tournament had to be on San Francisco's Stern Grove courts, near the daily press and television cameras.

|

| The editor's favorite croquet trophy--a Jaguar hood ornament mounted on a silver pedestal which reads, "Project Jaguar Media Croquet Challenge Champion, 1992," leaping prominently among his family mementos, endangering a fifth-century BC Greek ox. |

My partner and I squeaked by with a 7-6 victory, and the trophy I won is one of my favorites, inscribed with the words "Project Jaguar Media Croquet Challenge." We never would have won in an extended contest.

The lessons to be gained from beating stronger opponents or losing to weaker ones are few, but now at least we can generalize on when and how they are most likely to happen. If you want a sporting chance to beat a stronger opponent, insist on playing a short game, choose a bad court, or best of all, combine those two conditions. That will give you the best chance of generating an entertaining story for the bar.

By lunchtime the next day, I was a game up in the semifinal. And then I broke. I was tired and cold and wet. I hadn't planned on lasting the whole week, and I didn't want the cost of another hotel night. That was the exact point when I realised I didn't have The Hunger. My technique's not bad, but I'll never have the mind set of a winner, no matter how hard I practise.

By lunchtime the next day, I was a game up in the semifinal. And then I broke. I was tired and cold and wet. I hadn't planned on lasting the whole week, and I didn't want the cost of another hotel night. That was the exact point when I realised I didn't have The Hunger. My technique's not bad, but I'll never have the mind set of a winner, no matter how hard I practise.

In the field of autism, there is this concept called "parallel play." You may see an autistic child on the playground with other children and it may look like they are playing together. But in reality, the autistic child is in his/her own world, perhaps mimicking the other children, but not really engaging with them. That was like my match with Jeff. He was playing his game (not well) and I was playing my game (as well as my game goes). Sometimes our two games overlapped.

In the field of autism, there is this concept called "parallel play." You may see an autistic child on the playground with other children and it may look like they are playing together. But in reality, the autistic child is in his/her own world, perhaps mimicking the other children, but not really engaging with them. That was like my match with Jeff. He was playing his game (not well) and I was playing my game (as well as my game goes). Sometimes our two games overlapped.

What's perhaps more interesting than the inevitability of upsets is the much greater number of near-upsets. Would-be giant killers often show a knack for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. As the end of the game approaches, each player responds differently. The stronger player tends to work through whatever technical issues were causing the "run of bad luck". Meanwhile, the weaker player can't help but think about the fact that he or she is on the cusp of a notable win. Thinking this way is almost guaranteed to take you out of your flow. Balance restored, the stronger player goes on to win.

What's perhaps more interesting than the inevitability of upsets is the much greater number of near-upsets. Would-be giant killers often show a knack for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. As the end of the game approaches, each player responds differently. The stronger player tends to work through whatever technical issues were causing the "run of bad luck". Meanwhile, the weaker player can't help but think about the fact that he or she is on the cusp of a notable win. Thinking this way is almost guaranteed to take you out of your flow. Balance restored, the stronger player goes on to win.

If you find yourself losing a lot of games normally regarded as big upsets, you probably need to look at your practice regime prior to events and possibly even your fundamental technique. If you drop the odd game every couple of years, don't worry about it. Just continue to dispassionately play the odds.

If you find yourself losing a lot of games normally regarded as big upsets, you probably need to look at your practice regime prior to events and possibly even your fundamental technique. If you drop the odd game every couple of years, don't worry about it. Just continue to dispassionately play the odds.

Near the end of the game, I heard Maurice Marsac say from the sidelines, "My god, Bob is going to win!" Win I did, and enjoyed my fifteen minutes of fame. I had beaten a much stronger opponent on a BAD court and nearly driven him crazy as well, as I later realized. The ice soon melted, and the rest of my tournament was undistinguished. But I did learn what breaks were about, by the end of the event. Now I categorize that experience as a BAD COURT triumph.

Near the end of the game, I heard Maurice Marsac say from the sidelines, "My god, Bob is going to win!" Win I did, and enjoyed my fifteen minutes of fame. I had beaten a much stronger opponent on a BAD court and nearly driven him crazy as well, as I later realized. The ice soon melted, and the rest of my tournament was undistinguished. But I did learn what breaks were about, by the end of the event. Now I categorize that experience as a BAD COURT triumph.