|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| The Game |

|

New Zealand's Quadway tops the chart in English testing |

|

by Bob Alman layout by Reuben Edwards photos courtesy of Martin French, Ian Plummer, Paddy Chapman, Chris Clarke, and Ray Atkins Posted May 7, 2014

|

The holy grail of croquet is the perfect formula for making top-level croquet as competitive as possible in order to produce the fairest result--which means that the most skilled player will be more likely to win and the least skilled player least likely to "luck out" by taking a break to four-back, grooming for partner, watching the opponent miss the lift shot, peeling partner through the final three hoops, and pegging out. In such a game, the unlucky opponent will have had just a few chances to hit in. But on fast ground with tightly set hoops that easily reject even close-in attempts, and balls with less than one-thirty-second inch clearance, the games and matches will be much more interactive. The "best" player will be compelled to exercise extreme care with breaks on fast ground, to position hoop shots close in and straight-on, and will surely be less likely to lose because of just a few missed hit-ins. That's the theory and the reasoning behind much of the testing in the recent hoop trials of the Croquet Association.

Leading up to the English Croquet Association's hoop trials in April of 2014 was a much tougher test, combining all the elements of creating a challenging competition: The 2014 MacRobertson Shield test matches in New Zealand, extending over almost three weeks, among the four top croquet-playing countries in the world, with most of the top-ranked players competing for their countries.

According to John Prince and vitual all the elite-player observers of the 2014 MacRobertson Shield matches, the Quadway hoops designed by Ray Atkins from Christchurch may very well have become the answer for international players wanting more challenging playing conditions and therefore more interaction during matches. The essential feature is the factor of adjustable hoop clearances made from the crown of the hoop. "A simple adjustment to an upright turns the narrow hoop into a more comfortable width...yet the hoop is returned to the same holes in the ground."

|

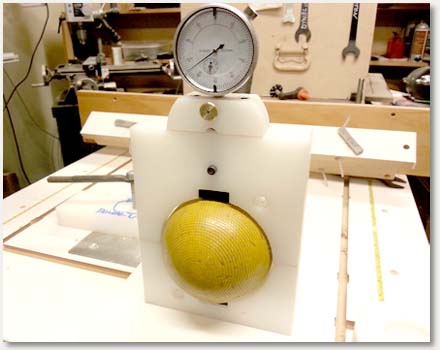

| The Quadway hoop in the ground at the United Croquet Club in the 2014 MacRob was a revelation to many international players who had never used them. Well-set in fast, hard ground, they can be mastered only by a high level of skilled play from the players--not just through successful hit-ins after more frequent breakdowns, but also precise, close-in and straight-on set-ups for hoops to keep breaks alive. |

| Understanding how the Quadway works |

|

Here's how the master craftsman describes his major design innovation.

Each carrot and upright is one unit. At the top of each upright there are 2 off-centre flats with a threaded hole in the centre. These flats locate into the crown and are central to the carrot. The round upright between the flats and the carrot is off centre, therefore when the unit is rotated 180 the round section moves either inwards or outwards. One carrot and upright unit has an off centre amount of 0.8mm, the other is 0.4mm offset. These amounts are doubled when they are rotated and become 1.6mm and 0.8mm, or 1/16 and 1/32" respectively.

To adjust a hoop size, unscrew one of the cap screws about 5mm, then wiggle the upright until it can be rotated. Re-tighten the cap screw. The ball diameters are approx 92mm, and the smallest size the hoops can be set to is 92.8mm = 0.8mm (1/32") larger than the ball. To set tighter than this it requires the hoop to be clamped to a smaller size and the hoop holes adjusted to suit.

- Ray Atkins, designer/manufacturer of the Quadway

|

The Clarke presence has made a huge difference not only in New Zealand croquet, but also in the quality of the lawns and the level of play (not even to speak of the Clarkes' contribution to the New Zealand team after Chris switched from England): According to Chris, "The hoops are much narrower than when I arrived in 2005 and the lawns are also generally faster for major events than they were five years ago. Our regs for hoop width were changed from 1/16 with an upward tolerance of 1/32 " to 1/32" plus zero minus 1/64" a couple of years ago."

And for the national organization, "We introduced guidelines for clubs wishing to host major events stating that they should be trying to produce 12-second lawns. I believe there is substantial scope for improvement in playing conditions at most United Kingdom venues, whilst at the same time accepting that UK weather is worse than NZ weather for generating optimal conditions."

So, in a nutshell, Clarke has actually contributed hugely to croquet globally by acting effectively on a local level. He has worked with local master craftsman Ray Atkins to help him produce what Clarke calls "the hoop of the future." (His major input, he says, was to suggest that the carrot be made square instead of rectangular.) The hoops performed well in the thorough test they were given on the United lawns in the 2013 New Zealand Open.

Clarke was confident enough in the hoop's merits that he successfully encouraged Croquet New Zealand to use them at all three venues of the 2014 MacRobertson Shield, for an even broader test, on lawns of varying texture and quality, not even to mention variations in weather and topography. The United lawns for the first half of the first test were slower than Clarke anticipated, because they had been flooded just two days prior to the start of the Mac. And the courts at Marewa were anything but level, producing an unusually tough challenge for players to approach them for close and straight hoop shots.

How accurate (in millimetres) must "accurate" be?

Well-set elite hoops depend upon balls with equivalently accurate dimensions. "Prior to the Mac at United," Clarke commented on the Nottingham Board, "Jenny and myself measured 20 sets of balls and created the following seven matched sets. Each set was marked to show which lawn it was to be used on and also which ball was the largest in millimetres and on which axis.

Largest dimension

Lawn U R K Y

1 92.06 92.09 92.15 92.14

2 92.06 92.12 92.09 92.09

3 91.92 91.98 92.03 92.00

4 91.91 91.94 91.95 92.02

5 92.01 91.98 91.97 92.00

6 91.96 91.99 91.96 91.88

7 91.95 91.93 91.92 91.94

According to Clarke, the graded balls were designated to remain on the courts assigned to them to guarantee that balls and hoops "matched" ideally throughout the event. With characteristic modesty, Clarke comments, "I think the equipment and methodology used in this process was an improvement on previous events."

|

| All balls are not perfectly round, and Chris Clarke accounted for variations in using this rig, which measures in millimetres, to create with his wife Jenny graded "sets" of Dawson balls for each court used in the Mac. |

Commenting on the vital importance of Clarke's measuring task, Graeme Roberts observed, "By sorting the balls into sets matched as closely as possible on their maximum diameters, we were able to produce sets where the maximum diameters differed by no more than 0.13 mm, with a mean of 0.07 mm.

"This shows that for the Mac, there was little variation between the maximum diameters of the balls in a set compared to the clearance of 0.4 mm. But note that for unmatched sets of balls the maximum diameters of the balls vary by up to 0.33 mm. With that variation, it is plausible in normal competitions where the balls have not been matched for the largest ball of a set to have 0.4 mm clearance on its maximum diameter while another ball could have 0.7 mm clearance on its maximum diameter. I consider that variance to be unacceptable.

Clearly, the 2014 MacRobertson Shield represented an unusual effort, combining the talents of extraordinary individuals pursuing a common goal, on the frontier of top-level croquet. Who else but Clarke and Roberts would engage in such an enterprise? Roberts says, "In my view, this substantial variability in the amount of clearance can make the running of a hoop set at 1/64" clearance into a lottery, since a player cannot know in advance which diameter of the ball will be horizontal when it strikes the hoop. The problem is still present when the clearance is increased to 1/32" but the relative variation is substantially reduced.

The United lawns, notoriously fast in the best conditions, add to the difficulty of running a hoop, in Clarke's view and in the view of most serious observers. Lawn Seven was originally designed for lawn bowls, and the Quadway performed as well on that lawn, perhaps, as a finned hoop designed for sand-based courts, and without damaging the lawn when removed. So add it up: When you put together the Quadways, the specially measured and grouped balls, and the very fast ground, what you have is a virtual guarantee of "difficult conditions"--the kind of play needed at top level in order to have a certifiably accurate and fair result, on the assumption that the more interactive a game is, the less likely it is that the weaker player will prevail.

Putting together the Atkins Quadways, the finely calibrated Dawsons, and predominately hard and fast surfaces, it's not surprising that the results of the 2014 MacRob in New Zealand pleased the Clarkes and others for whom meticulous standards at the top are essential in the further development of the sport. The results absolutely matched the predictions made on the basis of the relative rankings of the four teams.

Most people would regard the most successful "test" of a new hoop design to be a long event with the world's best players in which the best team--the one with the most highly ranked players--actually won the event. That's what happened in January in New Zealand.

The 2014 MacRobertson Shield as a test of the Quadway

The 2014 MacRob turned out pretty much as predicted, with the hosts (New Zealand) as slight favorites over England, and with Australia besting the US. If the US loss was greater than the Americans team expected, part of the issue could have been the hoops--the Atkins Quadway. The difference made for the Americans was two-fold: First, they were unaccustomed to the hoops; second, they had very little practice learning how to score a hoop that so easily rejected balls squarely in front.

These hoops are different in several ways: Instead of carrots in the ground, the Quadway has "parsnips" which are square, and responsible, some say, for the extreme difficulty of running a well-set hoop. In addition, the hoops are "unfinished"--that is, not powder-coated, which makes them more "sticky."

|

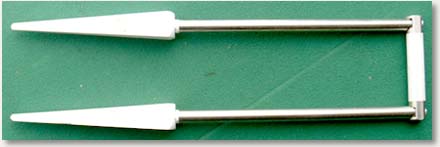

| One of Quadway's unusual features is the square carrots (Alan Pidcock has dubbed then "parsnips") which testing indicated makes a significant difference in the difficulty of running a hoop. |

These are the effects of the Atkins and other hoops that the recent (2014) Croquet Association hoop trials determined made an actual difference in the outcomes. Because the Atkins possessed two of the three most desirable qualities in making hoops more difficult (the square parsnips and unfinished steel) they were deemed the best hoops currently available for the usually soggy soil of England.

The British testers were less certain about the other "difference" factor of the Atkins--the adjustability of the hoop legs, accomplished with two screws in the crown. In fact, the rigidity of newer hoop designs with thicker, strong crown, helps to maintain accurately tight settings almost as well as the expensive "adjustable width" factor. But as Atkins states, not just minute differences in ball dimensions, but also changes in those dimensions throughout the day in varying temperatures, will always be a legitimate concern for managers and meticulous groundsmen. That makes the fast and easy adjustability of the hoop a major factor in the quest for an ideally "difficult" hoop.

All the groundsman needs to do is lift the hoop out of the ground, rotate one or both the hoop legs using the screws on the crown, drop the Atkins back into the original hole, and invite the players to continue.

Clarke himself has a different point of view on the hoop's unique value: "The four dimensions of an Atkins hoop have little to do with making it difficult. They exist so that at the end of a top class event, all the groundsman as to do is undo the screws and flip the wires to make them 3 3/4" and then drop them back in the identical holes for club play. No need to have different holes or go around fiddling with the hoop holes with a screwdriver to make them wider. Just a simple change; use the same holes but make the hoops much wider.

"When you put a hoop in the ground with an Oakley hoop clamp and then take the clamp off, it will normally try and return to its 'natural width,'" Clarke explains. "Since Atkins hoops have four 'natural widths', they can be set so as to minimise the 'springing back to natural width' problem."

How the Quadway is adjusted from the crown

The Quadway hoop is made of three separate parts--two uprights and a crown. These attach via a screw on each side of the top of the crown, and each upright can be seated into the crown in two different orientations, allowing for four different width settings. In other words, the slightly broader (or narrower) face of the hoop presented to an incoming ball will effectively adjust the clearance of the ball and thus the difficulty of running the hoop.

|

| The screws in the crown of the Quadway are its most distinctive feature, allowing the equipment manager of an event to adjust the clearance given the balls by turning them on one or both sides to change the dimension of the upright as it confronts an incoming ball from the front of the hoop. |

As Paddy Chapman commented in his recent report in the Croquet Association's Gazette, "This adjustability factor means that clubs can use just one set of hoops per lawn, and the hoops can be set either for normal club play or international play simply by rotating the uprights to a wider or narrower setting. The shape of the carrots also makes them very easy to reset if necessary - something that is a weakness of finned hoops."

How can competition be made more challenging at top level?

A major topic of debate in the last several years has been the danger of Association Croquet becoming "too easy" at the top level--that is, not very interactive--which tends to make it possible for weaker players and teams to do better than expected as a consequence of good luck. The introduction of Advanced and Super Advanced rules has improved the game with respect to interaction, by introducing more baulk line lifts. (In the game as originally played, one could go all the way around to rover and set for partner with impunity.) With more interaction, however, the "luck" factor is vastly reduced, because each player needs to hit in with more frequency.

But as former American international team member Damon Bidencope observes, the most telling conclusion of the conversation on "making the game more interactive" has now shifted from the laws to the equipment. Now, "The general imbalance between in-player and out-player at the top levels can be meaningfully addressed by an equipment change, not a laws change."

The statistics from the 2014 MacRob reveal a startling improvement in interactivity--everything from almost 50 percent fewer triples to very long matches, up to 11 hours. So the 2014 MacRob, with well-set Atkins Quadway hoops at all three venues, has set a new standard at top level.

How top-ranked players score the Atkins Quadway

Kiwi Michael Wright reports, " I have now played in tournaments using Atkins hoops at several clubs, with soil conditions ranging from very wet to quite dry. I have found the hoops to be significantly harder to run in average conditions (compared to standard hoops), and quite tricky in very dry conditions with hard soil. I am sure they are an improvement to the standard, and our club has just ordered some sets. It appears that my experience with these hoops is representative of most, if not all, of the senior players that have used them. That should end the debate."

Not really. The debate will surely continue for some time, as other hoop manufacturers try to compete on the basis of quality, price, and features.

Samir Patel on the English team played in the MacRob with Quadways for the first time. He comments, "At Mt Mauganui, the Quadways didn't put up much resistance until the slurry was used. Then they were probably the best set hoops I can recall in a sand court since the Superhoops at the World Championships at the NCC."

|

| Paddy Chapman's follow-through in a close-in stroke through the Atkins Quadway, on United's lawn five. |

That's not quite the way the hoop-shooting looked to New Zealand croquet legend John Prince, viewing part of the MacRob at Marawa for the Australia vs New Zealand test, where the courts were the quickest and the hoops seemed the most rigid, on uneven ground. He observed that players managed these conditions "by loading the boundary usually with the pivot ball, making a close approach, and running the hoop very firmly off the court."

Nevertheless, Prince joins a near universal chorus of top-player approval of the tougher conditions, which he characterizes as "a move away from an almost total emphasis on hitting a single ball straight, to being required to also play with greater accuracy and control."

Steve Jones, viewing the MacRob at more than one venue, commented on the "problem" of too-difficult conditions, "even for the top-ten players, at Napier. Because of high lawn speed and windy conditions the hoops there were too tight and too rigid. There are three main conditions that effect croquet playing: lawn speed, hoop width/rigidity, and weather. If two of these are harsh, it is an acceptable challenge for elite players. If all three are harsh, croquet playing becomes too difficult for everyone." On the other hand, "The hoops were too easy on the first three days at Mt. Maunganui, on slower lawns with a bit less wind. On the last two days, the lawns were fast and the challenge was about right."

All of these comments suggest that the Quadway constitutes a major improvement in hoop design, by facilitating easy and fast adjustments in the hoop width without making new holes or changing the conformation of the existing hoop holes.

Improvements in testing technology and equipment

According to Martin French, who conducted the recent Croquet Association Hoop Tests, "Previous tests have used two bits of kit: a ramp designed to deliver balls straight at a hoop - but by varying amounts off-centre, and a plank which lets you hit a peel through an angled hoop with reasonable precision. Both have their problems: the ramp deliberately puts top spin on the ball - but by how easily these balls run hoops even very off-centre, this is clearly very different from the actual hoop stroke most players can produce. And the peeling plank is fairly imprecise and it's hard to get reproducible results: you have to manually hit the stroke, so no two strokes are at identical speed. It's also evidently possible to "pull" the peel ball into or away from the near wire, and affect the results significantly."

So a ball-hitting machine was produced, simply enough--basically a mallet pendulum. The American pro Bob Kroeger posted a video of one made recently in America, and French easily made a British version. "We can't assume it will produce a stoke matching many people's hoop strokes - especially for close angled hoops, when many players hit very hard or make make the ball jump. But the pendulum machine should yield a better result than the previous plank and ramp."

|

| French made this "tonker" to more closely imitate a player's hoop stroke than the previous method of rolling the ball down a ramp. |

French and the official CA and WCF tester Alan Pidcock identified three factors in the 2014 hoop trials that seem to show positive benefits when seeking an "elite" hoop that works in typically damp English soil. (It seems easy enough to set a challenging hoop in hard dry ground):

* square carrots

* the "grippiness" of uprights

* the mass above ground, especially at the crown.

French reports, "Last March we compared against a reference hoop an Atkins Quadway and another hoop with square carrots (which Alan Pidcock likes to call "parsnips" to distinguish them from carrots) which Bill Aldridge had prepared for us. Both square parsnipped hoops were more challenging to run from an angle than the reference hoop, the Atkins more so than the Aldridge test hoop.

"However, we also had suspicions that the grippiness of uprights with modern powder-coated hoops was a real problem, so overnight, we stripped the powder coating off the bottom four or five inches of the Aldridge test hoop, leaving a bare steel finish. The Atkins is bare stainless steel already. The next day, the two parsnipped hoops were much more comparable."

The problem with modern powder coating is that it's often like Teflon, and you end up with (wait for it....) "non-stick hoops". But when you remove the paint, you create another problem--not just the tripping risk, but also, French notes, "some people have pointed out that at some stages during the day as the sun moves to behind the hoop, the edges can actually be quite difficult to pick out from the background, which they have said upsets their aim. If we confirm that more massive crowns make a difference to the challenge, these larger crowns could easily be painted white to address the tripping risk."

And why might square parsnips be better than round carrots? French says, "Our surmise is that when run from in front, the parsnips present a flat face to the ground and so are much less likely to 'squidge' the ground out of the way than a round carrot, where much of the "frontal area" is presented obliquely to the hole that is trying to resist its movement. And when tried from 45 degrees, the cross-sectional area presented to the ground from the diagonal of a square parsnip is very much greater than of a round carrot of a similar size."

How the Quadway was developed

Chris Clarke gave the local manufacturer of the hoop--Ray Atkins--a lot of input and tested the hoop at the 2013 New Zealand Open before ensuring that the hoop would be used at all three venues of the 2014 MacRobertson Shield, also held in New Zealand.

The hosts of the 2104 MacRob--New Zealand--were also the favorites, and they won by a fair margin over the second-ranked England. Australia came in third, and the US fourth. All these results matched relative rankings of the teams.

American Jeff Soo commented of the Kiwis, "They routinely bashed through to the boundary. And they did much, much better at getting close, straight shots at the hoop. They would get 1- to 2-foot position with some pretty long rolls." And later, "My day ended with an 18 inch, straight on shot. My ball ended up about four feet directly to the side of the hoop. There was no such thing as a hoop shot you could take for granted, unless you started in the jaws. That's not an exaggeration -- a 3-inch straight hoop shot required full concentration to make sure you didn't blob it or fail to get far enough through to roquet."

The Canterbury Croquet Association owns ten sets of Atkins hoops and five sets in permanent use at Clarke's United Croquet Club. Chris Clarke sums up his current evaluation of the Atkins. "They have proved popular with both elite and club players and have stood up to their first year's play well." Clarke's one reservation is whether the Quadway's adjustable screws will last over many years or decades of use. Only time will tell, so that part of the story of "the hoop of the future" is necessarily incomplete, for now. But in February of 2015, another top-level test of the remarkable Atkins hoops will doubtless be made at the Golf Croquet World Championships in New Zealand.

The distant and more evolved future

Martin French, a visionary at heart, still seeks a more evolved solution, which may be polyurethane sleeves on hoop legs to make them grippier: "We won't know until we've worked on it whether polyurethane sleeves are practical or effective, nor how thick they need to be to have an effect. Dave Trimmer has ordered some material to start some experiments. I suspect (but I'm happy to be proved wrong) the ideal hoop would be square parsnips, screwed onto stainless steel uprights (removable to fit or change the sleeving) welded to a fairly substantial crown. We'll see if my speculation is right. I don't expect we'll be fitting sleeking to existing hoops."

To nail down the point of all this exploration: "It's worth reminding ourselves we aren't seeking a better everyday hoop. We already have perfectly good everyday hoops that work well for clubs and most tournament use--and these start from £260 per set. It is only top-class Association Croquet which has been demanding a more challenging hoop when set in typical damp soil ("easy conditions"). In the near term, perhaps the Croquet Association might buy a dozen sets of the Atkins hoop for its premier events and a few of the biggest clubs might buy a set or two so their top players can get used to them-- although our experiments with grippy uprights might mean we can develop an 'elite hoop' for the Croquet Association within the next year instead."

|

| Seven of these "test" hoops, with Don Oakley's 4-fin designed for sand-based courts on the far left, and the Quadway on the far right, are all "legal" according to the English Croquet Association guidelines for equipment, except for the massive Egyptian hoop (#5); the apparent effectiveness of its greater mass above ground argues for expanding the guidelines. The best performers were unpainted hoops with square parsnips. |

Damon Bidencope agrees: "This equipment by its nature is transportable between venues that plan to hold top level events. If these hoops (or Superhoops in the US) can be provided by national associations for their top tier events, that would reduce pressure and resources on the host venues. The Superhoops we designed for the US were an attempt to solve the same issue in sand based courts, and they work. Clearly the New Zealand solution provided a true test for their mix of surfaces."

The US "Superhoop" was not in the recent hoop trials, but an improved version of it, from Don Oakley, who financed its development, tested well. The Oakley 4-fin (or "Premium") performs just as well as the Superhoop, Oakley maintains, and is less damaging to the sand-based lawns on which they're used.

French concludes, "Atkins has created a good elite hoop, no question. It is notable though from our tests that while the Atkins (and the Egyptian hoop) improved the critical angle by around 5 degrees, the test hoops with grippy uprights had a further 10 degrees of improvement. If we can find a way to reproduce this effect in a reliable design which we can have made at reasonable cost, this would be a bigger step forward--a true Elite AC Hoop."

So in 2014, the immediate pathway to the croquet's holy grail seeks a way around the comparatively high cost of the Atkins. The current price of a set of six hoops is NZ$900, and the price of the dibber (the hole-maker, which is an essential part of the Quadway system) is NZ$275, plus freight and insurance from depot to door.

Atkins himself defends the price, not just on the value of the expert workmanship required: "When comparing the price of a set of Quadway hoops against the price of a set of balls, the hoops are almost too cheap!" He notes that air freight is charged mainly by weight, but sea freight is charged mainly by cubic capacity, and 26 sets is equivalent to a cubic meter. So 26 sets would be, perhaps, an "economical" way to buy Atkins hoops in quantity.

THE MANUFACTURE AND DISTRIBUTOR:

Ray Atkins, designer of the Quadway hoop, is a club player in Canterbury with great skills as a precision tool maker. As an apprentice engineer he discovered early a natural flair for designing tools and machines. After coming to New Zealand in 1971 as a toolmaker, he started his own business--designing and making cutting tools for many industries. He started to play croquet in 1985 and after "retiring" from work in 1998, busied himself in manufacturing mallets and designing trophies. Inevitably, he has now begun to manufacture hoops, in Christchurch. One of the two most distinctive characteristics of his stainless steel hoops are square carrots (made of medium tensile steel) which promote rigidity and stability; the other is the adjustability factor, engineered with screws which enable one to rotate the uprights and thus choose between four different width settings. The dibber is a vital part of the Quadway system. Square holes to receive the hoops are made by driving the dibber into the ground with a maul. The square holes when formed with the dibber remain the same for all hoop settings. To set the dibber vertical, there are two pins to place a spirit level against. The hoop face is used to align the other axis. See the link at the top of the article for more information on the Atkins Quadway.