|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| People |

|

A collector’s memoir: The game and the art |

|

An interview with Tremaine Arkley by David Appleton Art captions by Tremaine Arkley Expanded from a two-part version originally printed in the Croquet Gazette Posted February 2, 2009

|

Although Tremaine Arkley no longer plays croquet, around twenty years ago he was one of the USA’s top players and a member of several Solomon Trophy teams. He also is the world’s most ardent collector of croquet art and memorabilia. When he and his wife Gail spent some time away from their Oregon farm to holiday in England, David Appleton met them in Barnard Castle for a visit to the Bowes Museum, lunch and a chat. The conversation between Tremaine and David continued by email. In this edit of their exchange – which constitutes a substantial croquet memoir - Tremaine recalls his introduction to the game and his playing days and then tells the story of how he came to start his collection and of his plans for it.

DAVID APPLETON: When did you start playing croquet, Tremaine?

|

| Tremaine Arkley in the croquet pavilion at the Resort-at-the-Mountain, managing and observing the Resort Invitational Tournament. This prestigious invitational, drawing the world's top players, was one of the sport's major annual purse events until it was suspended in a resort management revamp. |

DA: So you took to this new game at once?

TA: I immediately bought some mallets, got a USCA Rule Book and started playing against local players. I quickly became the best player in Oregon on non-regulation long grass courts, mostly at the local fairgrounds. This was also, unbeknownst to me, the beginning of my edgy relationship with other croquet players, as I was an aggressive player who played to win and discarded the “nice guy, let’s have fun” approach on the court. It also improved my game as my opponents became more determined to beat me, which required me to play better. I had a goal for the future and Oregon was my stepping-stone.

DA: When did you start competing nationally and how did you get on?

TA: Right away I started to go to regional and national tournaments and quickly discovered that my game was not competitive when played on unfamiliar smooth regulation croquet courts, of which there were none in Oregon. I also discovered, much to my amusement, that the sport had a Hall of Fame and that Harpo Marx was a member. I thought it couldn’t be that bad with Harpo in the Hall of Fame. It wasn’t until much later that I discovered that Jack Osborn [founder of the US Croquet Association] created the Hall of Fame as a marketing ploy for croquet!

I also noticed that most of the players playing the USCA version of six-wicket croquet were not particularly good athletes. They were not young, and most were rather casual in the competitive aspect of the game. They did not take it seriously. Many were social players with non-athletic lifestyles, mixed in with a few well-to-do dilettantes. These were the people who kept the game alive in the US, started the USCA, and wanted it to remain as their domain. They were not particularly interested in outsiders joining their exclusive croquet clubs.

DA: What made you so sure that you would succeed in croquet?

TA: As a former state champion in college badminton and a competitive four-way [downhill, slalom, jumping and cross country] skier all my life, I knew if I just learned the game and the strategy and had a better court on which to practice, I would be able to become very competitive. I also had great hand-eye coordination and loved geometry. I just knew. My confidence was overwhelming.

I also realized that since there were so few people playing this sport that my chances of success were very good!

DA: Who were your early teachers?

TA: I immediately signed up for the USCA Coaching School in Palm Beach. I had some excellent instruction there, particularly from Nigel Aspinall, Ted Prentis, Kiley Jones, Jack Osborn and the Australian Ron Sloane, who was a member of the Australian team competing against a US team as part of the school.

It is amazing how one remark can sometimes make a big difference. Ron told me after watching my determined efforts and raw skills that still needed lots of work: “Tremaine, with your potential someday you will be an American champion”, plus many other words of personal encouragement. I took his words to heart and believed what he said.

I watched with dismay the US getting humiliated by the likes of John Mager, Sloane and others. I also watched our best and knew it was just a matter of time before I would be at their level. But I realized that to rise to the top level I would have to have access to a regulation court on which to practice. The nearest courts of any quality were in San Francisco and at the Seahawks (NFL Football team) practice field near Seattle where one of the owners, Ned Skinner, was a croquet player. I could also move to Florida.

DA: When you started playing croquet in 1980s you spent a lot of time in Palm Beach. Who were your influences there?

TA: The ladies! My four favorite people at that time were the Grande Dames of croquet: Libby Newell, Lee Wood, Lee Olsen and Nelga Young. These women were the heart and soul of croquet at the time and provided the financial and organizational support for the game. Two other women also provided a youthful spirit to the game; Suzanne Mahoney and Anne Robinson. All six were very kind and generous people. They made my participation in croquet in Palm Beach an enjoyable experience.

DA: Where did you find a court in Oregon?

TA: I didn’t. So I built what was at that time the best croquet court in America at our farm in Oregon. I converted a sheep pasture to my court. It was irrigated with an automatic underground system and seeded with a Penncross bentgrass. My court was a laser levelled 128’ x 110’ greensward 1/4" off corner to corner. We mowed it with a nine-bladed walk-behind greens mower. I practiced for months upon end in between maintaining my greensward, at times mowing four times a week to maintain the fastest grass speed possible. This was before the courts were built at Meadowood and Sonoma-Cutrer in California. I provided each of them with consultation and later sources for their Penncross bentgrass seeds, which are all grown by farmers in Oregon.

During this time my play at tournaments improved and I started to place and even win some events. I think a lot of people wondered where I came from and how I improved so fast.

|

| This abstract of a croquet court by Sidney Rowe, a well known painter in the Pacific Northwest, was commissioned by Tremaine Arkley three years before the artist's death. The oil is painted on an unframed board and hanging at the Arkley farm in Oregon. |

DA: The investment and the practice continued to pay off?

TA: I continued to play enthusiastically in other tournaments that year, including many at Palm Beach, Arizona and California, where I met the personalities of the organization and made many friends. At heart I can be a likable person! For my enthusiastic support of croquet, in 1984 I was named USCA Rookie of the Year.

The following year, in between tournaments, I spent an inordinate amount of time day after day practicing on the court. I was obsessive. I had the time and desire to master the game: the split shots, the one ball shooting and all the rest.

DA: When did you become interested in the International game?

TA: I had bought Ron Sloane’s book in Florida, properly inscribed “to a future champion,” and concentrated on his chapter on croquet shots with his engineer’s discussion of angles and other fine points. I had to prove to myself what did or did not work based on my body and particular stance and grip. I also started to learn the rules of Association play.

While reading his book and with a quick visual introduction to the International game in Palm Beach, I realized the USCA game was an anomaly and not the game played throughout the world. When reading Ron’s book I also had to absorb ideas in the International game.

Earlier the US teachers and top players were slavish on how one should stand, grip the mallet, swing, and look when playing the game. It seemed to me that style rather than content was the rule. Originality was not encouraged. How you looked was most important to them. It also included what you wore. (If you’re white you’re all right!)

I quickly realized that I was never going to be, nor did I care to be, like other players. A close non-croquet-playing friend of mine who knows me well told me: “Tremaine, to succeed you must develop your own style and stop trying to imitate them. Play your own game and create your own persona on the court. Do not be like them!”

I continued to practice, practice, and practice daily throughout the year, well into the evening, and improved my shot-making ability. In retrospect I realize I was probably the only person in the USA doing that much practice, as almost all the players at that time were treating the sport as a game, and not to be taken too seriously. They also had jobs and family obligations. I was working but retired in 1987 and had a wonderful wife Gail who supported me to try this out to see if I could make my mark. I was a croquet maniac on a farm in Oregon on the best court in America living my own dream, determined to be one of the best and make all those US teams and win.

That year and the following year I won or was runner-up in USCA rules Regional and National Championship plus other local and regional tournaments.

|

| Fades Away When The Break Begins, pen & ink by Ernest Howard Shepard, published in Punch, June 17, 1931. The male opponent on the sidelines is obviously not pleased to see the lady take his game away. |

TA: Yes, he was and it took a lot of convincing from his core supporters and friends whom he could trust within the organization for him to change.

In 1986 the first Sonoma-Cutrer World Singles Championship was held, and it became obvious that this event was going to become a fixture on the US croquet calendar, outside the USCA’s influence. During this period a breakaway group of croquet players in the US formed the American Croquet Association (ACA) focusing on the International game. It was a small group but its membership included many strong US players who were interested in playing Association Rules and had played the game for many years, mainly in Arizona.

During many USCA/CFA [Croquet Foundation of America] board meetings, mainly in Florida, we discussed how to counter and/or support this movement. Many of us in the group urged Jack, the dominant voice in the two USCA organisations, that we had to recognize the International game and start our own national championship. We told him we could not ignore the world game and needed to put the organization behind it if we were ever going to become members of the MacRobertson Shield sometime in the future, and to step into the world of international croquet.

DA: When did you start playing regularly in International tournaments?

TA: By late 1986 I started to play the International game. I realized to compete at the world level I had to play Association Rules. The USCA game was going to continue to remain an isolated club version of croquet and would never become accepted throughout the world, despite our founder’s intensive efforts to proselytize it to other world associations as well as to the clubs in the US..

In 1986 I concentrated hard on learning the world game. The next year I was selected to play on the USCA International Challenge Cup team against world players and subsequently on a USA National Team against Great Britain and then in the second Sonoma-Cutrer World Championships in California. These three 1987 events were great learning experiences for me on the tactics and strategy of the Association game, the shots required and composure needed to win.

DA: You were on the first Solomon Trophy Team that played at Cheltenham. What was that experience like?

TA: In 1987 Reid Fleming and I won the first Association Rules National Championships Doubles, held at the Bon Vivant Croquet Club in Bourbonnais, Illinois. That win gave me a place on the inaugural USCA Solomon Trophy Team to be played at Cheltenham in 1988. Reid, as a Canadian, was not eligible for the team. .

We were an inexperienced team that year, but the highlight of my career at that point was when Peyton Ballinger and I broke the duck and won the only USA match that year in doubles against William Pritchard and Colin Irwin 2-1. We were over the top despite the 20-1 final team score.

Peyton, who later died at an early age, was a calming influence on me on the court, encouraged me during my play, and was a great person.

DA: In the next four years or so you had some good results at the top level. Which ones gave you most pleasure?

TA: Following the Solomon I played in the first WCF World Championships at Hurlingham in 1989 and made it to the final 16, the highest-ever American finish, and replicated that finish in the 1992 Worlds at Newport, Rhode Island, again the highest USA finish, including a block win over Reg Bamford. In between those events I was on all the Solomon teams but one. I also played in many British Open Championships.

|

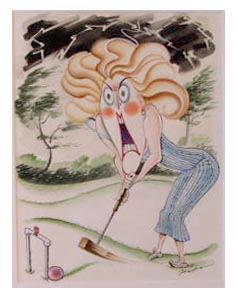

| Fergie Causes a Storm on the Croquet Court is a 1995 pen & ink & watercolor drawn by John Jensen and published for the magazine of Thomas Goode's Luxury Goods Shop, which the royal family frequents. |

I was beginning to improve my game and during the 1991 Solomon I beat Chris Clarke 2-1, and in doubles with Bob Kroeger beat Clarke and Fulford 2-1. I also took one game from Nigel Aspinall in our singles match. After I won that game and was a bit full of myself, Nigel reminded me (after he won the best-of-three match) that I needed to win two in a best-of-three! In the 1989 Solomon in doubles we posted a 2-1 win over Openshaw and Avery.

During this time I made many friends from overseas, including Bernard Neal and his wife Liz; William Pritchard and his mother; Keith Wiley, the Irwins, John Solomon; the youngsters at that time, Chris Clarke, Rob Fulford and David Maugham; David Openshaw, Stephen Mulliner, Reg Bamford, Phil Cordingly, Simon Williams, Keith Aiton and many others. I was beginning to feel very much at home overseas and made some very good friends that remain so today.

During this period I also sponsored a few international tournaments, with purses, at my court in Oregon. I invited Clarke, Maugham, and Fulford. One year all three were guests at our farm, and one evening David Maugham started a fire in our kitchen showing us the correct way to make chips boiled in oil for some amazing chip butties! Gail, my wife, saved the day (and house) by tossing the contents of a box of baking soda on the flames on top of the stove that were beginning to creep up the wooden walls of the kitchen while David was frozen in inactivity. The chip butties were fantastic!!!

It was at this point in my croquet playing that I think I made a bit of a jump to a higher level where the top players would no longer watch me play and say, “Don’t worry, he will eventually break down and we’ll get the innings back!” This was also true of many of the other US players who were becoming competitive on the world scene. We were now becoming serious international competitors.

My best teaching experience was when I spent time with Rob Fulford on my court when he would walk with me when I was running a break and show me where to place each ball during the shots and tell me why. He also complimented my single ball shots, which I depended upon and needed to keep me alive on the court, as I was still a bit of a sloppy break maker. These lessons were very important to me in the future.

DA: You took a break from croquet near the end of 1991. Why, when your game seemed to be getting stronger?

TA: Near the end of 1991 I took a six-month hiatus from croquet after many successful results in the 1990 and 1991 season, including runner-up in our International Rules singles and winning numerous other international and local tournaments. I felt I was hitting my peak, but I was getting bored with the political social croquet scene. I was also burned out. I needed a refreshing break.

I had been involved with Foxy Carter, president of the USCA, in the negotiations to have the US included in the 1993 MacRobertson Shield. I was a member of the USCA Management Committee and an officer and board member of the Croquet Foundation of America. At that time these two boards were intertwined. By then I was fully involved in the politics of US croquet.

When it became apparent that we would be included in the MacRobertson, every serious player in the US geared up to be selected. The competition was going to be fierce for the six positions on the team.

After six months of no play I felt rested and ready to compete again. My good friend and croquet mentor, Foxy Carter, encouraged me to get back into play and earn a spot for the upcoming world championships in Newport, Rhode Island, where he and I were part of the small group putting that event together.

Due to a variety of reasons, much to my chagrin, I was not selected as an official US representative to the Worlds that year and to earn a spot was forced to play in one of our two qualifiers for the additional four slots. I chose to play in the Eastern Qualifier at Palm Beach, where I felt more comfortable than the one in Northern California, where I had had some personality conflicts with a few players.

At the Eastern Qualifier I won my block then had to face newcomer Dan Lott in one of the finals for a slot. In the first game of the best-of-three match I was casual, loquacious, talking to spectators and not concentrating and lost decisively. It was at that point that Foxy came up to me, before the second game, and told me to shape up, stop socializing, sit down, focus and play my game. He and his wife Mary wanted to see me in Newport. I did, too, and beat the unsuspecting and overconfident Dan +26, +26. I then went to the Worlds and tied for ninth, along with Reg Bamford whom I beat in the block, and then for the rest of the season, now highly motivated, I put together a tournament record that would make it hard for the selectors not to choose me for a spot on the MacRobertson Shield team.

I played in the Solomon, the British Open, Chattooga, and in many tournaments in the US and had the strongest results of all the players that year, including winning the USCA International Rules national singles title, beating all the major US players who were contending for the MacRob Team. I was totally in the zone. In retrospect I think I realized that this was the final goal I had set for myself in croquet, and I got lost in the ambiance of the moment and never played better.

During this period I played under the code: show me a good loser and I will show you a loser! I was not a very pleasant person to face on the court as I was intense and played to win, not to socialize. I had a supremely arrogant attitude on the court, projecting a sense of superiority. I suspect I burned some bridges in the process but I knew if I did not have a great season I would not be selected.

DA: What influence did the US being included in the 1993 MacRobertson Shield have on you?

|

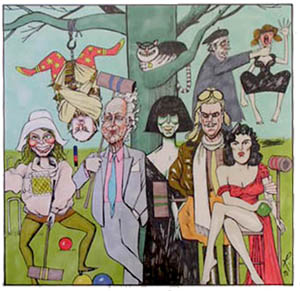

| Macabre group under tree. This pen & colored ink by William Rushton illustrated the front cover of the October 1993 issue of The Literary Review published in London. The figures shown (l-r) are: Sarah Miles, Harry Houdini, Peregrine Worsthorne, Cheshire Cat, Anne Rice, Howard Hughes, Jane Russell, and French existential philosopher Louis Althusser, strangling his wife. |

Before selection it forced me to focus and concentrate on my play and build my competitive style. I knew I had to play my best that year to make the team, as I still remained a bit of a non-conformist within the politics of players. There were two players on the eventual team who tried to have me kept off the team due to personality clashes. I was not very tolerant of fulsome people. I think I was a bit too rough for many who, at times, I considered too insincerely “nice”. When I played singles I projected a lot of hostility and negative thoughts toward my competition while on the court, while keeping inner conversations to a minimum and ignoring court and personal distractions. It was an amazing state of mind.

When the Selection Committee was making their final decisions the head of that committee called me and said that my season record and current status as National Champion made me an obvious pick. However he said that he and other committee members and a few team members wanted my assurance that if I was selected I would be good! I kept my reply to myself and told him of course I would be good! I felt like I was back in grammar school talking to the head teacher again.

I had poor results in the event. I broke my favourite mallet before the start of play, did not have a replacement and spent a lot of time borrowing various mallets from my friend Bob Jackson, who was my mallet maker.

However, after the Shield I was at the top of my game and followed with a very strong Sonoma-Cutrer tournament, being the only US player to pre-qualify. But by then I could feel my interest in the game flagging. I had achieved all my croquet-playing goals. I think I had MacRobertson Shield burn-out, and at the end of the following year I stopped playing and quit cold turkey. No more playing goals were left and I did not want to spend the time and energy on high-level competition. It was easy to quit!

DA: Tremaine, it has been interesting hearing about the progress of Association Croquet in the United States and your own part in that, but I suspect we would not be talking at such length if that was all you had done. Let us move on to your interest in collecting croquet memorabilia and particularly croquet art. What got you started?

TA: When Gail and I traveled in England and the Continent before my croquet days we visited museums. Then later, playing croquet in England, I wondered if there was any art related to croquet. It was a passing thought that, as it turned out, became a major interest in my life – some would say an obsession.

To begin with, my driving force to collect croquet art was a wish to save the history of the sport. I don’t know where this collecting drive came from. Maybe I have a collector’s gene, as both my parents were collectors, or maybe it was my tendency to cheer on the underdog, the unrecognized. I had a horrible feeling that much of the art of this obscure sport would be lost if not put in one place. Nobody was doing this in a single-minded effort and I felt it was important enough to try. I knew I could not collect everything but I hoped I could acquire a significant amount.

DA: What were the first items you acquired?

TA: Our first introduction to croquet art came from Colin and Chris Irwin, who were selling prints of Hadham Hall showing a court on the lawn. We bought one and then I started exploring what else was available.

I bought a watercolor of cats playing croquet on the beach and quickly developed relationships with a few gallery owners in London and later in New York City. I slowly started buying croquet art: mainly paintings, drawings, prints and illustrations. This was around 1988

I soon discovered that there were major 19th century artists who had painted croquet images – Renoir, Winslow Homer, JJ Tissot, Manet, Monet, Berthe Morisot and others – but these were already in major museums and private collections. I thought, “Okay, these have been saved” much to my financial relief! - so I kept focusing on what was available.

|

| Le Croquet etching and drypoint by James Jaques Tissot, 1878. The original oil on canvas version of this work is at The Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario. Mrs. Kathleen Newton, Tissot's mistress and a favorite subject in most of his London Period paintings, is shown with her two daughters in the garden of the home they shared in London's St. John's Wood. |

I also discovered that, except for Richard Pearman of Bermuda, no one was seriously collecting croquet art and there was not much on the market. It made my decisions easy since there was not much to choose from. It was not like baseball, tennis or golf art where one had hundreds of choices. So I waited until something became available, checked it out, and if it was not over-painted or damaged we added it to the collection. I then had it matted and framed to museum standards for preservation purposes.

DA: How did you find the items?

TA: I spent an inordinate amount of time on the telephone contacting auction houses, galleries and likely individuals all over the world, making friends, developing relationships. This was before the use of the Internet was common.

Chris Beetles from London was very influential in helping me develop the collection, with his sound advice and ability to locate some rare and hard-to-find pieces. He has a gallery in St James’s on Ryder Street and is one of the foremost dealers in 19th and 20th century art. He and his wife Carol are now very good friends of ours. I also had a lot of help finding American illustrations from Walt Reed, the owner of Illustration House on West 25th Street, New York.

Since I was the only person who was asking about croquet art I went to the top of their lists as a potential customer. I also discovered I could negotiate favorable prices when they realized I was not interested in resale but more concerned with establishing a collection for historical purposes. Thus I was not competing in their field of art dealing. I was always gratified when, as time went by, my sources told me of others looking for croquet art and they had had to tell them that they already had a primary customer, therefore discouraging potential competition.

DA: Is there a particular focus for your art collection?

TA: At first I let what was available on the market dictate the focus. I was interested in any piece that had croquet as the subject. I had no idea what was going to be available. It soon became apparent that one theme was English paintings from the 1860s to the 1890s featuring women. They were the dominant figures and shown positively. The middle of the 19th century, during the initial croquet craze, was when women were finally liberated from the stuffy confines of the Victorian parlors to the outdoors where they could mingle with men, often without chaperones. We began to document an important part of the early women’s movement in the paintings and prints of that period.

Many of the painters were English with solid reputations and a strong exhibition record in England and elsewhere. Most would be considered minor painters today. Examples would be Philip Calderon, Charles Green, Heywood Hardy, George Elgar Hicks, Clement Lambert, Benjamin Leader and Alfred Perrin.

There is also a large part devoted to the 19th Century English School, by which I mean unsigned pieces or those with unidentified monograms. They can be spectacular pieces - including a collage under glass in its original walnut frame: there are pugs in the foreground with a croquet ball and a woman croquet player running a hoop, gazing out at a hot air balloon in the sky floating over Gopsal Hall, in the background. The background is watercolor but cloth, silk and feathers are used for the woman’s outfit and hat, while the mallets have been cut out from paper and painted.

We also found many 19th and 20th century cartoons including all the early Punch croquet cartoons. We are especially fond of John Leech’s 1862 piece A nice game for two or more, which we have in large and small prints.

|

| Aunt Emily Made One Mighty Swipe. This 1961 pen & ink by Ernest Howard Shepard, a frequent illustrator for Punch, recalls a golden era of garden croquet at its peak a century earlier. |

It became obvious to me that croquet cartoons were a metaphor for satire, both political and social, as well as other cultural comments. The beauty of croquet was that the cartoon image did not have to be set on a croquet lawn, all it required was some reference to croquet to make the point, unlike tennis or golf which were restricted, in most cases, to where the game was played.

DA: What else is in the collection?

TA: The body of the collection is fine art: oil paintings, watercolors, pastels, pen & inks, illustrations, cartoons and a variety of other media. We also have over 3000 prints and other paper items including newspapers, magazines and advertisements. The photography collection is a recent addition, with over 1000 items including a nice American segment. The croquet books include all the major first editions, many author-presentation copies, and some very rare one-of-a-kind books with outstanding illustrations.

DA: Any particularly special books?

TA: When I started collecting I added most of the first edition books to the collection plus duplicates when I found them. Many are inscribed or presentation copies from the author. I have all the majors including H.F. Crowther Smith’s and Tollemache’s various books and an autographed copy of Notes on Croquet by R.C.A. Prior. A particular favorite of mine is Expert Croquet Tactics by Keith Wiley with a very long and humorous note to me by Keith. He also sent me a long personal letter included with his paperback edition.

I have Maud Drummond’s personal copy of Dr Leonard William's classic Croquet, including the author’s amazing obituary she glued inside the front cover. I bought Maurice Reckitt's signed presentation copy of Croquet Today, including his note: “Don't leave all your thinking till the end of the break”, and eight signed photos of players in the book. At the 1989 World Championships at Hurlingham I mentioned this purchase to Betty Prichard and she told me she always wondered what happened to that book after it was borrowed and never returned to the [English] Croquet Association office!

During my collecting period I met David Drazin and realized here was the major croquet book collector, and I happily pulled out and left it to him! His goal of saving that part of croquet history through the books and periodicals was in good hands. He also saved me a lot of money! From time to time I picked up little rare gems with croquet illustrations. I also buy the first edition books where I have the original croquet illustration.

DA: What is your oldest item?

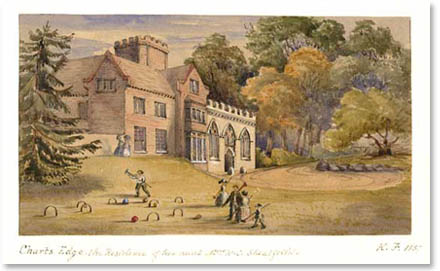

TA: The oldest piece is an 1857 watercolor painted at Charts Edge in Kent by a young woman named Kathleen Fry, whose descendents still live there. Interestingly women are featured in a great many of the early pieces, usually in dominant poses or roles, while cartoons often show men as buffoons and otherwise make some sharp social criticisms.

|

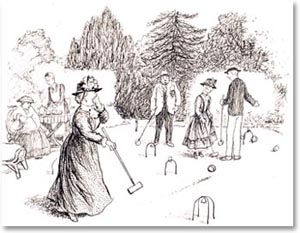

| This early watercolor, painted in 1857 by a young Victorian girl named Kathleen Fry who lived there, depicts croquet at Chart's Edge, Kent. |

DA: Who are some of the illustrators in your collection that those of us in Britain might recognize?

TA: We have five illustrations by Ernest Shepard – best known for his illustrations of Winnie The Pooh – from Punch in the 1930s, and three by William Heath Robinson – equally famous for his silly contraptions – one entitled Roof Croquet from his book How to Live in A Flat.

|

| Roof Croquet. This 1936 pen & ink by William Health Robinson helped to illustrate the book "How To Live In a Flat," published by Hutchinson, London. Robinson was one of England's most popular and distinguished illustrators of his time. |

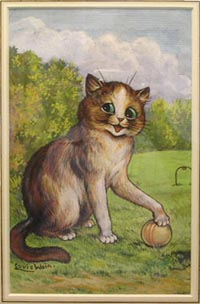

We also have items by Leonard Leslie Brooke (the father of one of your Home Secretaries) from the book Johnny Crow’s Party and a caricature, the subject of which is still unidentified, by Edmund Dulac (a Frenchman who worked in England for most of his life). Other names you might recognize are Edward Ardizzone (who wrote the Little Tim stories), Quentin Blake (best known for his work with Roald Dahl) and the famous cat illustrator Louis Wain.

DA: What have you from magazines and newspapers?

TA: We have all the major prints from the 19th century. These are the ones mainly found in London Illustrated News, The Graphic (a British weekly illustrated paper which ran from 1869 to 1932), Punch, Harper’s and other popular periodicals of the day. We also collected vast numbers of 19th and 20th century advertisements featuring croquet in some form, and a huge numbers of prints from a variety of other magazines, newspapers and trade cards.

There’s a particularly interesting series in The Graphic showing the courts at Sheen House in Richmond from the 1890s, featuring many women players in elegant outfits at the Championships.

DA: You said you also have photographs.

|

| Cat Capturing the Croquet Ball is a watercolor with body color circa 1920 by Louis Wain, the celebrated Edwardian cat artist. |

I have a solid collection from the US, many back to the American Civil War and others in rural settings and backyards. I began to realize that croquet was a very popular activity for a wide range of social classes.

DA: Are all your images historical or do you also collect contemporary croquet art?

TA: I do. When I started I was fortunate to meet Liz Taylor and acquired from her some lovely paintings and original card illustrations including one transaction at Hurlingham from a personal boot sale during one British Open! I also bought watercolors from John Prince in New Zealand including all the months of one of his croquet calendars which was a satirical series of players from England and elsewhere.

|

| Liz Taylor is a contemporary British painter and croquet player whose numerous croquet-themed oils and drawings have evolved through several distinct styles. |

I have also been buying some modern surrealistic paintings and a quantity of outsider or primitive croquet art. One is so weird I keep it stacked against the wall at the farmhouse in Oregon. It is by a woman, Ann Harper, who is a painter and a therapist.

DA: Is it so very strange?

TA: It shows a young woman on a croquet court, thin and sick with a bald head, looking very ill. She is holding a mallet, ready to hit a ball in front of her. There is another ball in the background. In the air a barn owl is flying away from her. Upon closer inspection the croquet balls are rolled-up baby barn owls. The colors are subdued sickly pastel tones. It’s about 2' x 2 1/2' – an unframed oil on canvas.

DA: Do you ever commission a painting?

TA: Rarely. I’m hesitant to do so because then I am obliged to purchase the piece even if I cannot stand it. However, in 1988 Natasha Ledwidge illustrated the cover of AE Gill’s Croquet, the Complete Guide published in London. I contacted her and bought the original, which I loved. I call it Hoity-toity croquet! I then asked her to do me a series of five pastels, which she completed in 1993. These have yet to be exhibited and are outstanding humorous pieces, including Nymphs croquetting and Napoleon in his study.

Matt Wuerker, a well known American political cartoonist, did a great satirical drawing for Z Magazine and I asked him to do some additional pen and inks for me. We collaborated a bit and he came up with some biting political pieces including the caricature of the 1993 USA MacRobertson Shield team and Crow Kay, a dressed-up bird set on the lawns of Hurlingham.

DA: Do you have a favorite painting in the collection?

|

| Barn Owls in Play. Anne Harper is the contemporary American artist who created this strange oil depicting barn owls as croquet balls. |

TA: My favorite is Le Croquet by Louise Abbéma, painted in 1872 when she was 14 years old. The painting is on long-term loan to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. She was a lifelong friend of Sarah Barnhardt. This painting has been widely exhibited, including in some first-rate Impressionist shows.

DA: Tell me about some of your American pieces.

TA: In America there was a period when members of the literary Algonquin Round Table used to spend summers at Alexander Woollcott’s retreat on Neshobe Island in Vermont. This gang included Harpo Marx, Dorothy Parker and many others; over the years they had many fierce croquet games on the island. We have an original drawing of the famous incident of Dorothy Parker playing croquet on the island, nude except for a garden hat.

A few years back I made a trip to Neshobe Island with a friend who knew the owner who had purchased the island from Woollcott’s handyman, who had inherited it from Woollcott. Everything was in original condition, including the infamous croquet court. We located all the croquet equipment in a shed, including Harpo Marx’s mallet. The owner was in the process of selling the island and we all expressed concern we would lose this piece of croquet history with the sale, so my friend’s foundation accepted the donation of all the equipment.

The island was subsequently sold to a family who maintain it as a non-profit concern dedicated to preserving the history of the island rather than commercially developing the property. We plan to give them the original Dorothy Parker drawing to be hung in Woollcott’s stone house on the island.

I have an oil painting set in the South during the Civil War period showing a plantation owner and his family playing croquet with women slaves in the background carrying bales of cotton on their heads, and I have many American cartoons and pieces from a group of Westport, Connecticut artists of the 1920s.

|

| A Game of Croquet, oil on canvas by Louise Abbema, 1858-1927, French. This painting has been in many Impressionist shows and is currently on loan from us to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. It was painted when Abbema, who was a long-term companion of Sarah Bernhardt, was only 14. The artist was awarded the Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur. |

DA: You are going to make a donation of the Dorothy Parker drawing and lately you have been giving away other parts of the collection. Are you breaking it up?

TA: As part of my goal of saving the history of the game through art I started to identify certain pieces that could be returned to their places of origin. I was not interested in selling pieces of art; I am not in that business. Recently I donated two pieces where I felt they belonged.

The first was to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh: an oil painted on canvas in 1864 by the Scottish artist William Crawford. It shows some of the children of a prominent Edinburgh family playing croquet in front of a cornfield. This large 4 1/2' x 5 1/2' piece will be the cornerstone of a room the gallery is remodeling to be devoted to Scottish sports.

The second was an oil painted on wood in the 1890s by George Howard, the ninth Earl of Carlisle. It is of four of his children playing croquet on the court at one of his properties, Naworth Castle in Cumbria. This year we met and spent the day at the castle with the current owners Philip and Elizabeth Howard and learned that the ninth Earl’s wife’s favorite sport was croquet! I was very pleased when Philip put the painting on the original easel used by the artist in the old library that looked out over the original croquet court - which is still extant! It was quite a homecoming for the painting.

The next day we met the curator at Castle Howard, another of the Howard family’s properties, where we were shown some early photographs of croquet and sketches of croquet done by the ninth Earl. They are in the process of cataloguing his vast inventory and plan to identify the croquet items now that they have been made aware of croquet!

|

| This caricature of an unknown person was drawn when the English artist, Edmund Dulac, 1882-1953, was part of a group of eccentric emigre artsts from Europe living in a grand English country house in flamboyant creative style, courtesy of their host, Viscount Lee of Farnham. |

TA: What to do with the collection in the long term was the question that continued to worry me as I was collecting and accumulating such a large volume. I quickly discovered it is not easy to donate something like this. Museums generally do not want it and if interested will only take the cream of the crop.

However, one particular dealer friend in London said that the volume after a period of time takes on a life of its own and acquires value in its historical content. So I made some attempts to find a home for the collection. Urged by my friend Foxy Carter and other members of the Croquet Foundation of America (CFA), the Newport Art Museum in Rhode Island agreed to house a Croquet Hall of Fame room and establish the room for exhibitions of croquet art over the years. This was at the time when the power of the CFA shifted to Newport away from Palm Beach.

The Newport Art Museum extensively remodeled the room and then held two croquet exhibitions in 1993 until 1995 with great reviews in the New York press. A future show was planned bringing some of the pieces held in major museums, including some Winslow Homer oils.

With a museum now attached to croquet art we adjusted our family trust and bequeathed to the museum the bulk of the croquet collection. It seemed like a sweet logical deal.

But politics in the CFA caused them to withdraw support for the Newport Art Museum and the Croquet Hall of Fame room. So everything went south as part of the mega croquet center being built in West Palm Beach.

This center was without a professional museum environment, climate control, a professional curator or any person qualified to handle a large collection. It became an amateur social operation again.

I still worked with the Newport Art Museum and curated two separate croquet art exhibitions there from 1999 to 2001 while the National Croquet Center was being built in West Palm Beach. The Newport Museum still had the lovely refurbished croquet room while waiting for the move to happen. We hoped we could work something out with the museum, but finally the CFA closed the door and left the museum.

I made some contacts with the CFA and USCA then about providing some interesting American pieces for the National Croquet Center, but they told me they were not interested. It seemed a shame but later I saw that some lovely 19th century prints donated earlier to the CFA by Foxy Carter were being sold on Ebay.

Not wanting to subject my donated collection to amateurs who might sell the donated pieces to the market or friends to raise money to help fund the Center, I decided to step away from the current situation in the US and try to find a future home for this still growing croquet monster elsewhere. It seemed to be growing daily.

DA: When did you start thinking about England as a possible site for the collection or part of the collection?

TA: I always had great relationships with people in England (and the rest of Great Britain and Ireland). Throughout my playing years in England I discussed the collection and recent acquisitions with many people who were interested in what I was doing and appreciated my long-term goals.

In 1997 the English Croquet Association held a croquet art show at the Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum as part of the Centenary celebration and we loaned some excellent pieces which complemented the outstanding show. At the dinner at Wimbledon I was awarded a lifetime achievement award by the Croquet Association for my contributions to the sport. I was overwhelmed; gobsmacked, I believe the expression is.

During this time Bernard Neal tried to establish a section at the All England Lawn Tennis Museum to formalize the sport at Wimbledon. Despite his efforts and the good intentions of the museum staff nothing came to fruition. However we subsequently donated to the museum some specifically tennis- and croquet-related pieces.

When John Solomon retired as President of the Croquet Association we decided as a fitting tribute we would donate to the CA in his honor some select pieces including trophies from the collection. We made some small donations during the British Open in 2008 and continue to work with the CA on this bequest, including some future long-range plans for a CA croquet art gallery or museum.

|

| The artist's signature is undeciphered on this piece from the European School, 1910. |

TA: Sort of. Recently I sent Chris Williams, the CA Archivist, a list of items we have identified to donate, and asked for his response. We are still determining what will follow. But this will be a careful process because the CA, except for its office in Cheltenham, does not have a secure place to store and display art. We are all working to resolve that problem as they plan to expand the clubhouse at Cheltenham.

One particular piece we’re giving is by HF Crowther-Smith, a 1930 watercolor of HT Pinckney-Simpson, a well known English international croquet player, and a second watercolor of his wife holding a riding crop, dressed in jodpurs, jacket, hat and tie.

We’re also donating a dry point etching by JJ Tissot of his well known croquet oil painting of his mistress and her children at his house in St. John’s Wood, completed in 1878.

Gail and I, with the help of Bernard Neal and the Cheltenham Croquet Club, are working on a plan where a later endowment from our Trust will help with the construction of an appropriate place to house and exhibit pieces from the Solomon collection and other items the CA owns.

DA: What about the balance of the collection, since only a small part is going to the CA?

TA: I’m going to break some news to you. Except for pieces earmarked to the CA and a few elsewhere, the collection will go in its entirety to the University of British Columbia’s (UBC) Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections section of their main library in Vancouver.

DA: That’s very interesting indeed. Why Canada, why UBC and why their library and not a museum?

TA: A museum is not the best place to donate such a large and diverse collection of art as I mentioned earlier. Museums are notorious for selling off parts of collections to buy other pieces and storing art out of sight for years. Generally museums are not research institutions. University libraries are. I also believe there is a lot to learn from the history of croquet, especially through the art, and this information needs to be accessible.

The Arkley family has a long relationship with UBC, the second largest research university in Canada. My father was born in Vancouver, BC, and graduated in 1924 from UBC as did his three siblings. He and my mother, from Seattle, both book and NW Indian art collectors, donated to the UBC Museum the art and to the Library what turned out to be the largest collection of children’s historical literature in Canada. They also included an endowment and scholarship to the School of Library Science. In the 1970s my father was awarded an honorary Doctor of Law by UBC for his support of the University over the years.

As the person in the family managing this endowment, I had the contacts with UBC and the opportunity to mention to the development office our croquet collection and our interest in finding it a home. They were hesitant but expressed some interest. I was told that the University Library is offered lots of collections but they turn down most as they have become more discriminating. They do not want to be burdened with low quality items they then have to store.

After I described the materials in the collection and some of the history of croquet, the Rare Books and Special Collections librarian and the development officer for the library made a trip to Oregon and later Seattle to look over all the materials, including the books, paper and paintings, illustrations, and the rest of the fine art including sculptures, and over a thousand 19th and 20th century photographs.

They were cautiously interested but told me that first the collection had to be vetted by UBC faculty and administration to see if it had any research interest or potential.

Later I was told by UBC that the Women’s Studies program was very interested in the role that women played in the early history of the sport, documented though the art, prints and books. Other areas of interest included croquet as an image in the history of cartooning from the 1850s to the present, outdoor and other 19th century costumes, the sport as played by all social and economic groups documented in the prints and photographs, and a few other areas.

When UBC accepted the collection I felt as if a huge load had been removed that I was unaware I had carried around for years. I had finally found a place where this collection would be preserved and available for research and study. I was getting it off my hands.

When I was in the midst of collecting, having acquired at that time less than 1000 pieces, I began to worry about what I was going to do with it. One horrible fantasy was that I would be forced to put two doublewide trailers on the farm behind the barn and open a Croquet Museum! Sort of like a Corn Museum or Hubcap Museum. I could see it heading into the realm of a crackpot collecting venture!

DA: How will this collection be made accessible to the public?

TA: The problem with many donated collections is to find the staff, resources and time to inventory, catalogue then digitize all the materials. Sometimes collections linger in library storage rooms before the cataloguing begins. We felt that the process should start immediately to get the collection out to the public.

So we made available to UBC a fund to start the process, including eventually setting up a web-site where the items will be available to view worldwide. In the future our Trust has long range plans to continue acquiring additional materials for UBC and to assist with the management of the collection.

DA: What consequences will the donation have for the UBC Library?

TA: With the donation in hand the library immediately looked at expanding to other sports and during this period acquired the largest golf book collection in Canada.

When large collections find homes at libraries and become available worldwide, other collectors then start donating their pieces to the library, which enhances and builds up the collection. That is how collections grow. Collectors are always looking to place their pieces somewhere and now they will have a home established for their croquet collections.

When all of this comes to fruition UBC will have the finest croquet collection in the world, larger than any public or private library, and an information network available to the public worldwide via a web-site on the internet. We plan to aid in the digitization of these materials and development of the site. It’s all very exciting, and we’re pleased to have created and to be in the process of leaving a legacy of croquet to the world.

DA: Tremaine, thank you for your time and congratulations on what you have managed to achieve. I look forward to accessing the UBC web-site and seeing some of the items you have described. Those of us who are fascinated by anything to do with this great game of ours have reason to be extremely grateful to you and Gail.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER, DAVID APPLETON:

David Appleton has been playing croquet since 1985 and is still

enjoying it immensely. He was probably at his best in the early 90s

when he represented Scotland in the Home Internationals (five-man

teams from Scotland, England, Wales and Ireland), played in the World

Championship, and first met Tremaine, but he thinks he still has a

few more triples in him before he calls it a day. Despite not really

enjoying travel, somehow he has managed to play in 15 countries.

In 1996 David produced, with fellow croquet player and cartoonist

Jack Shotton, a book called "The Lighter Side of Serious Croquet".

Inspired by Tremaine and Gail's gifts of old cups and medals to the

Scottish Croquet Association (SCA), he is now working on a history of

the Scottish Croquet Championship from its beginning in 1870 until it

lapsed in 1914, though he feels this book may sell rather fewer

copies than his first effort. David has been chairman, treasurer and

coaching officer of the SCA. When he isn't involved with croquet he

solves and composes crosswords.