|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| People |

|

Ellery McClatchy passes into croquet history |

|

by Mike Orgill and Bob Alman layout by Reuben Edwards Posted November 9, 2011

|

It's hard to think of American croquet without thinking, also, of the Swopes, Jack Osborn, Chuck Steuber.... and Ellery McClatchy. Ellery is the last of them to pass away, and he is the one who most closely and steadfastly committed himself to the growth and development of USCA croquet for the longest time - for more than 30 years. Especially because he so determinedly stayed in the background whenever possible, for his own good reasons, we need to now make known something approaching the full scope of his contribution to the sport and the people in it. The recollections of many friends in the second half of this tribute story tell of much but not nearly all his public and behind-the-scenes benefactions to many, many people and projects. Mike Orgill begins by piecing together the complete arc of Ellery's steadfast devotion to USCA croquet, beginning in the 70's.

|

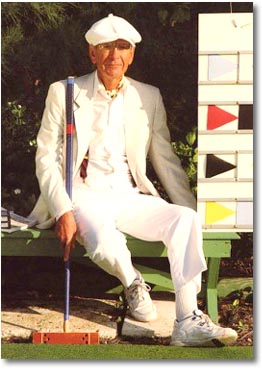

| Bert Myer scanned this portrait from his 1992 USCA Croquet Annual. It was taken at the Beach Club in Palm Beach in 1990. Ellery enjoyed keeping a good deadness board. It helped him maintain focus, he said, on a game he wanted to watch. |

Ellery was born in Fresno, California, the son of Carlos and Phebe Briggs McClatchy. Carlos McClatchy was the founder and editor of the Fresno Bee and the son of C. K. McClatchy, the owner-editor of the Sacramento Bee. Ellery McClatchy’s grandfather, James McClatchy, a reporter for Horace Greeley in New York, followed his boss's advice and went West, eventually buying part ownership in the Sacramento Bee.

Ellery was the last of the fourth generation of the family that founded one of the most prominent American newspaper chains. He played a major part in another dynasty, his passing virtually putting to rest the generation that brought about croquet’s American renaissance.

He was a member of the "greatest generation", the cohort that, regardless of social standing, stood up to fight the threat of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. He served in the US Army during World War II in New Guinea and the Philippines. During the post-war years he designed and built passive solar houses on the east coast and engaged in boat building, among other interests. He became deeply involved in the family business, serving the McClatchy Corporation as officer and board member for 28 years.

|

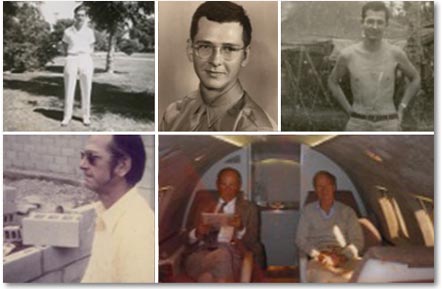

| The first photo, with Ellery in white, is pre-WWII or during it. The next two are army pictures. Another shows Ellery at a construction site, probably one of his houses; and the last is with his brother C.K. on the company plane. |

With family and friends Ellery played the backyard game as a diversion. Serious croquet first touched him in 1979. Xandra Kayden, a political scientist and activist, gave him a backyard set in 1966 as a housewarming gift. They used it to play in the sand on the beach at Ellery's home on Fire Island, New York. "That was the old game," she told Croquet World, "with lots of cheating and dragging of feet to create a path for the balls to follow."

But the croquet bug didn’t take hold of McClatchy until ten years later, and again Kayden was responsible. After taking up the game more seriously while she was at Stanford University, Kayden stayed with Ellery while trying to raise money for a study of the political parties in New York where her ownership of a Jaques croquet set made her something of a figure in the Manhattan croquet scene. While staying with Ellery in 1979 Kayden took McClatchy to a "croquethon" in New York’s Central Park organized by Jack Osborn’s nascent USCA. After that, recalls Kayden, "it was all over." The croquet bug had permanently infected Ellery. He immediately began making plans to blast out the koi pond at his house in upstate New York and put in a croquet court.

|

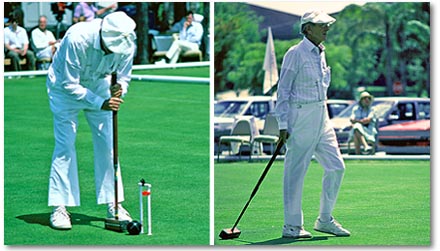

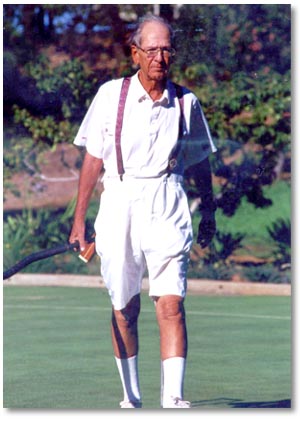

| These pictures from PGA in 1987 show Ellery's shooting style - as well as his trademark habit of dragging his long mallet behind him. Bert Myer photos. |

Meanwhile, Kayden resettled in Boston and established a croquet club. The formation of the USCA had invigorated American croquet, and Kayden was in the thick of it. And so was Ellery. He established an annual tournament at his home in New York's Putnam County. He took many lessons from croquet’s foremost pro, Teddy Prentis. Ellery would tell friends that he took more lessons from Teddy than anyone in history. He began traveling the croquet circuit, competing in as many tournaments as he could.

A few years passed and Ellery decided his court just wasn’t good enough. "He blasted out a good part of the hillside," Kayden remembers, "built it up again, and after great personal expense had the most beautiful, smooth and even court I’d ever seen."

Now Ellery faced a new problem: recruiting players. He had a magnificent court and few people to play with on a regular basis. And he had a solution: he would drag his friends and associates kicking and screaming into croquet.

Maryholt Maxwell was a friend and business associate he had known before the croquet addiction hit. She had a real estate office in downtown Carmel, New York, and Ellery had worked with her to sell a small cottage he had lived in while building his larger estate on the mountain.

Ellery had not taken the architectural license exam, but he practiced architecture in Putnam County in a serious way, building passive solar single-family houses. Eventually he, Maxwell, and another friend, Dick Tucker, became partners. Ellery designed, Tucker did the engineering, and Maxwell did the marketing. This partnership was the core of his croquet cohort.

Erv Peterson photo. |

"His response was: Be here at 2:00 PM. I went."

Dick and Martha Tucker and Maxwell joined Ellery for endless games on the hilltop court, playing during the day and into the night under the lights. "If you think Ellery was a kind teacher," Maxwell said, "you are mistaken. He was the most demanding coach we ever had. He would tell me to hit the ball to a certain spot on the line (before we knew what stalking meant, or what the line on the top of the mallet was for) and if I was three inches off I had to do it over and over again until I got it right on the spot."

Eventually Ellery’s croquet passion led him away from upstate New York. There was not enough activity or competition in Putnam County. Ellery sold his New York house in 1983 and moved to Palm Beach, Florida, the American croquet center in the early 1980s. The USCA had moved its headquarters from New York to south Florida, where the croquet snowbirds from New York and other northern climes spent their winters.

It was not only croquet that brought Ellery to Palm Beach but an entire community to which he could belong and contribute. Ellery was a quiet, private person. He had lived most of his life up to this point away from his native California and had made his own way apart from the family newspaper business. Croquet presented him with something he perhaps had not known he needed: a meaningful structure, a way to organize his life.

Bert Myer photo. |

Once in Palm Beach, Ellery immersed himself in the croquet world, playing in every tournament, building up his grand prix points until he ranked seventh in the country on that scale, even though, he recalled, "not with a very good playing record. There weren’t that many people playing, no handicaps, and early on there was only one flight, double-elimination."

Ellery did more than just play; he immersed himself in croquet politics. "You work not only to improve your game but to help out and solve the problems that exist within the game," he said in an interview on the occasion of his induction into the Croquet Foundation Hall of Fame.

Ellery did more than just play; he immersed himself in croquet politics. "You work not only to improve your game but to help out and solve the problems that exist within the game," he said in an interview on the occasion of his induction into the Croquet Foundation Hall of Fame.

Just as Ellery moved to Palm Springs the American croquet world was embroiled in an intense controversy. In the forties and fifties a light-hearted rivalry grew up between the Eastern society croquet aficionados and the Hollywood crowd. The East-West split was something of a lark then, but with the formation of the USCA, the split in the eighties became much more consequential. Captain Forest Tucker presided over the Birnam Woods Croquet Club in Santa Barbara, and he played only the British game, loudly decrying "the Osborn dead game." He mentored a bunch of middle-class upstarts out of the Arizona Croquet Club who learned the British game on their own, apart from Osborn's organizational efforts back East. The eastern players were totally unaware of this western contingent until the Arizonans turned up at a national tournament in Central Park. Stan Patmor, Ren Kraft, Rory Kelley and later Jerry Stark were among the leading western lights.

|

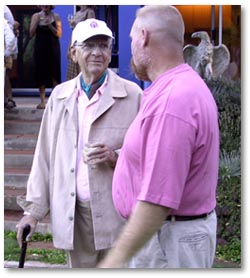

| Holding the remnants of his "McClatchy" cocktail, Ellery is obviously enjoying a chat with Jerry Stark. Jerry was usually the tournament director of Ellery's spectacular annual fall invitational. Erv Peterson photo. |

Jack Osborn came to croquet much as Ellery had: his exposure to the game induced a lifelong obsession that changed his life. A "Mad-Man"-like advertising man, Osborn was a member of New York cafe society and habitue of night spots and tony venues all over the Northeast and Florida. Osborn set out to transform American croquet into an elite sport that would attract an upscale demographic, a sport, moreover, with Osborn at its head. To this end he created the USCA and aggressively marketed croquet as "America’s fastest growing sport." Of course it was nothing of the sort, as Osborn had no data to back up his claims, but exact truth doesn’t matter to a master promoter; the only thing that matters is creating enough plausibility to attract media and corporate attention. And attract it Jack Osborn did. As McClatchy settled into Palm Beach, croquet seemed on the verge of becoming the "latest thing." At least that was the picture Osborn was painting.

|

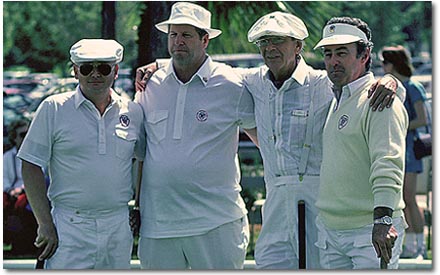

| Bert Myer photographed this quartet at PGA in 1987. Left to right, they are Renn Kraft of Arizona, Archie Burchfield of Kentucky, Ellery, and an unknown fourth figure. |

Jack Osborn and his coterie wanted croquet for themselves and for their kind of people. In developing its rules the USCA had consulted with the British croquet association, with help from Nigel Aspinall and John Solomon. But Osborn kept the deadness game that had been played in one form or another at country clubs in Florida and the northeast.

|

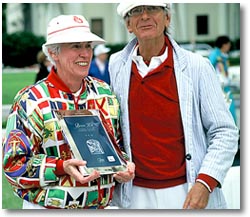

| Margaret Hull holds their plaque at the PBCC Invitational, January 1994, as they enjoy their success as doubles partners. Bert Myer photo |

The two groups were soon at loggerheads, even though the Arizona boys had seemed to compromise by inaugurating their own major tournament, the Arizona Open, under USCA rules. They still wanted recognition for the international game, something that Jack Osborn was not willing to give.

Ellery was the natural mediator to bridge the East-West gap. He associated with both sides, encouraged players of all socio-economic backgrounds to play, and joined tens if not scores of USCA clubs all over America to encourage each one to grow. He worked closely with Osborn, was cultivated and rebuffed many times, and realized that the USCA and the Arizona faction were hopelessly at odds.

Ellery's mediations failed, at first. The USCA was turning a blind eye on international croquet. So unbeknownst to Osborn and the East Coast crowd, Ellery suggested that the Arizona boys form their own association, the American Croquet Association. This rival organization would promote international rules in the United States and join the international competitive croquet community.

Ellery's mediations failed, at first. The USCA was turning a blind eye on international croquet. So unbeknownst to Osborn and the East Coast crowd, Ellery suggested that the Arizona boys form their own association, the American Croquet Association. This rival organization would promote international rules in the United States and join the international competitive croquet community.

Ellery also supported Xandra Kayden's efforts to encourage collegiate croquet, encouraging her to teach both forms of croquet, on the grounds that the US would not be able to compete internationally without a thorough knowledge of the British game. He also funded Kayden's basic book on both games.

"I couldn’t help it," Ellery recalled in an interview. "Some of the people I played with -- like Stan Patmor and the other rebels on the west coast -- had become persona non grata. We had to use the energies of the people in the west, the people that Osborn had alienated. We couldn’t waste these people. They got the international game accepted."

Ellery assisted the Arizona faction even though he, like most of the east coast players, preferred the American game. Despite this he encouraged international play by supporting players in international competitions and otherwise greasing the wheels so that America could become a presence on the international croquet stage. The threat of the growing "rebel" organization in the West impelled Osborn to establish USCA-sanctioned competitions for the international game, after all, including a national championship. By preempting the ACA's agenda, Osborn preserved the USCA as the dominant national organization, at the cost of sanctioning the international game.

Jack Osborn alternately wooed and rejected Ellery, as he did with many other prominent croquet figures. "The fact is," Ellery recalled, "Jack was not a politician. When he wanted something, he included you, but when he got what he wanted out of you, he didn’t talk to you again. A real politician will come back and stroke you. I didn’t mind because I wanted to help croquet, but it was so obvious."

Jack Osborn alternately wooed and rejected Ellery, as he did with many other prominent croquet figures. "The fact is," Ellery recalled, "Jack was not a politician. When he wanted something, he included you, but when he got what he wanted out of you, he didn’t talk to you again. A real politician will come back and stroke you. I didn’t mind because I wanted to help croquet, but it was so obvious."

No one knows how many gifts and grants Ellery gave to worthy croquet players and projects, some worthier than others. "I don’t think it’s such a good idea," people have heard him say about one project or another, "but I’m not going to be a dog in the manger." If it was possible a project would benefit croquet, Ellery was there to support it both vocally and financially.

|

| This collection of American croquet greats was photographed by Bert Myer at the Breakers in April,1993. At least three of them are still alive in 2011. Left to right, they are: Gene Goldberg, Libby Newell, Ellery McClatchy, Bill Campbell, John Donnell, (back) Don Degnan, Jack Osborn, (back) Herbert Swope, Fred Supper, Pat Supper, Barton Gubelmann, (back) Butch (Ernest) Bessette, Cathy Tankoos, Foxy Carter. |

Ellery served as the Croquet Foundation's president twice, from 1991-94 and for one year after the death of Don Degnan in 1997. In that position he worked with many other generous individuals whose support has made American croquet possible. One such man was the late Jack McMillin, the first president of the Foundation. Ellery donated $100,000 to the National Croquet Center to acknowledge McMillan’s contribution to croquet in difficult times. McMillin had been recruited by Osborn to form the Foundation, but the two soon clashed when McMillin did not always follow Osborn’s lead. "And in those days," Ellery told his friends, "Jack Osborn could make life difficult for people who didn’t do what he wanted them to do." Ellery felt that McMillin hadn’t gotten his due, and he used his NCC donation to remedy that.

Ellery’s croquet patronage is legendary, but his croquet career did as much for Ellery as it did for American croquet. Surrounded by family and friends at his Sacramento memorial, Xandra Kayden spoke of the impact croquet had on Ellery. "The more engaged in croquet he became," she said, "the more he came into his own as a quiet but strong supporter, mediator and friend to many players around the country and the world.

Ellery’s croquet patronage is legendary, but his croquet career did as much for Ellery as it did for American croquet. Surrounded by family and friends at his Sacramento memorial, Xandra Kayden spoke of the impact croquet had on Ellery. "The more engaged in croquet he became," she said, "the more he came into his own as a quiet but strong supporter, mediator and friend to many players around the country and the world.

"Building on that experience," Kayden continued, "he also came to play a critical role in his family and the family business as the quiet listener and mediator who could see things from both the inside and the out."

|

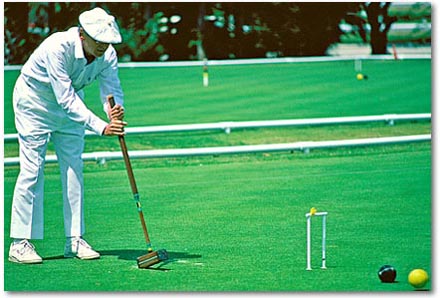

| A side view of the New Zealand mallet in action. Erv Peterson photo. |

As Ellery resettled in Northern California, the San Francisco Bay Area was undergoing a croquet resurgence of its own. The driving force was Tom Lufkin, a Hollywood producer turned horticulturalist, residing in Santa Rosa. Tom had a deep croquet lineage, having been involved in the last stages of croquet's Hollywood golden age, having played croquet on Sam Goldwyn's lawn with the likes of Howard Hawks, Gig Young, David Niven and other luminaries. Lufkin played often at the Beverly Hills Croquet Club, and yearned to establish its equivalent in the Bay Area. By 1980 he finally succeeded in planting a club at Stern Grove in San Francisco. Going beyond that success, he was a major factor in persuading Brice Jones to build the courts at Sonoma-Cutrer in Sonoma county, and Bill Harlan to follow suit with the courts at the Meadowood Resort in Napa county. These two venues soon brought croquet luminaries such as Neil Spooner, Damon Bidencope and Jerry Stark to northern California and croquet in America took a quantum leap.

|

| One casual dinner out during the Ink Grade invitational was at Taylor's Refresher in St. Helena. On the right, from the front are Reuben Edwards, layout editor of Croquet World Online and longtime member, top player, and corporate events manager at the San Francisco and Oakland Croquet Clubs; Mike Orgill, co-author of this article; Elaine Fong of the San Francisco Croquet Club, John Leonard, Ellery, and Rhys Thomas. On the left, Jerry Stark blocks our view of at least a half dozen others. Erv Peterson took the picture. |

Ellery was soon a member of both Sonoma-Cutrer and Meadowood, as well as San Francisco and was a large factor in the sponsorship of croquet at all of these venues. In the late 80s and early 90s, Northern California was the region that supplied most of the players on the USCA'S international teams, as the USCA was invited to join Great Britain, New Zealand, and Australia in the quadrennial MacRobertson Shield team events among croquet's "big four." In this period, many top-ranked players from around the world enjoyed Ellery's hospitality at Ink Grade after their games at Sonoma-Cutrer or Meadowood.

Ellery made Ink Grade a quiet yet magnificent refuge imbued with his unerring taste and trademark color palate. With the help of his staff, Edie, Gil, Mikko, Marlee and others, Ink Grade became a croquet paradise and a horticultural showplace. There he proved himself at bottom what he had worked all his life to become: an auteur producing memorial experiences and meaningful environments for his family and friends.

Ellery made Ink Grade a quiet yet magnificent refuge imbued with his unerring taste and trademark color palate. With the help of his staff, Edie, Gil, Mikko, Marlee and others, Ink Grade became a croquet paradise and a horticultural showplace. There he proved himself at bottom what he had worked all his life to become: an auteur producing memorial experiences and meaningful environments for his family and friends.

The Ink Grade Invitational exemplified Ellery’s gifts and became an historically significant croquet venue. Perhaps American croquet’s most coveted invitation, Ink Grade was a convocation of like-minded and influential croquet players the like of which the croquet world had never seen and will probably never see again. An invitation to Ink Grade ushered you a world of intense croquet competition and warm companionship, an environmental croquet tapestry that only Ellery could weave.

|

| Lunchtime at the Ink Grade invitational is on the plaza between the pool house and the swimming pool. The tennis court and croquet lawn are visible in the background, and one of several golf carts Ellery rode around his hilly estate. Peterson photo. |

Ellery rejected most praise, seeing it as overblown, but in his heart he must have known how special the artistry of his friendship was.

|

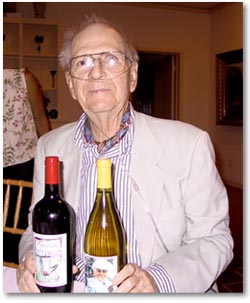

| The "Ink Grade" label for both white and red wines were donated to his tournament each year by Charlie Smith and Erv Peterson, who snapped this photo. |

In his last years Ellery battled emphysema. Since coming back to California he had kept a house in Palm Beach, but by 1991 he had moved permanently to Pope Valley when he could no longer travel by commercial airplane. He also established a base near Mission Hills Country Club in Southern California and helped make it the largest croquet venue in the west.

He had been on oxygen since the middle 1990s, but had always gamely competed. In the mid-90s he endured a risky operation that removed his diseased lung tissue. It was a last-ditch effort to prolong his life, and it worked as well as could be expected. He lived on for more than a decade, still mentally sharp and focused, still playing a pivotal role in the affairs of his family business and American croquet. Those last ten years showed something that had resided under the surface of Ellery’s long life: his emotional and physical courage. Despite debilitating illness he pushed through his suffering to engage with his life and his friends. He was still contributing and making things work as his life drew to an end.

He had been on oxygen since the middle 1990s, but had always gamely competed. In the mid-90s he endured a risky operation that removed his diseased lung tissue. It was a last-ditch effort to prolong his life, and it worked as well as could be expected. He lived on for more than a decade, still mentally sharp and focused, still playing a pivotal role in the affairs of his family business and American croquet. Those last ten years showed something that had resided under the surface of Ellery’s long life: his emotional and physical courage. Despite debilitating illness he pushed through his suffering to engage with his life and his friends. He was still contributing and making things work as his life drew to an end.

|

| This cocktail hour photo was snapped by Erv Peterson in front of the pool house at Ink Grade. Peterson photo. |

William Ellery McClatchy was a major factor in American croquet’s endurance into the 21st Century. Other figures will arise to energize croquet; this is the pattern we’ve seen over the last 150 years through croquet's booms and busts. But the croquet world has lost someone who, in our grief, seems irreplaceable.

|

| Bert Myer captured this iconic image of Ellery at Meadowood in a pro-am event sponsored by Domaine Mumm, which carried with it substantial cash prizes. Damon Bidencope arranged the event, perhaps most memorable for a medieval-style banquet in a wine cellar, with everyone sitting at a single very long table, sans dining utensils. It ended in the biggest adult food fight in croquet history, with several players struck by flying chickens. Some people refer to this brief late 80's period of lavishly sponsored events with big purses as a "golden age" of American croquet. |

For me, Ellery always exemplified grace.

Rich Curtis |

|

We learned to carry a fistful of dollar bills... I came across Ellery many times in the late 80s and early 90s during my croquet play in Palm Beach and on the West Coast. I always found him to be succinct and dignified — and one of the several colorful characters at the center of the USCA's and 6-wicket croquet's development as a serious game. He was a fun player to watch, dragging his long-handled mallet behind him as he walked to his ball, and confident in his shotmaking -- but not always as successful as he would have liked, to which he reacted demonstrably. He was a competitor. And a good sport. He dressed with what might be described as "restrained sartorial flamboyance" on and off the court. A bit rumpled at times, but always stylish and in good taste. He was different. He also was generous to a fault, quietly underwriting countless croquet projects and always eager to help out when a venture passed his scrutiny. All he asked was: Is it good for croquet? In Palm Beach, he often entertained all tournament participants — friend and foe alike — with open bars and sit-down dinners. Players learned to carry a fistful of dollar bills for the valet car parkers maintaining order in his neighborhood. In those times, we were all rich for the experiences Ellery provided. Bert Myer |

|

When Ellery was your friend, you knew it. He had a calming effect that overcame so many of life's problems. While he didn't invent the phrase, "Don't sweat the small stuff," he personified it. He was one of the last of the true gentlemen of croquet, in the style of Bob Clayton or John Young, men who had class without trying, it was just natural to them. I will miss him and all he stood for. Dan Mahoney |

|

This is how I met Mr. McClatchy.

After years of working in the hotel business I had just started going to a culinary school in West Palm Beach when somebody told me that a businessman in Palm Beach was looking for a part time personal chef. A couple of days later there I was being interviewed by Mr. McClatchy. His tables and work desks were piled high with documents, drawings, papers, hand-written odd looking notes, catalogs from Tiffany and Steuben, and ashtrays filled with cigarette buds. Right away there was some kind of connection. I got the job. The first dinner party was scheduled for the following evening, so he could get his friends' opinion about my cooking skills. Next morning I asked how he liked the dinner, and the answer was, it was "good", and he didn't say anything else, so I was little concerned. After a couple of years I knew if he said it was "good" that translated to "very good." The next year I was invited to work at Ink Grade, where he had his annual Ink Grade invitational croquet tournament every August, and I kept doing that for the next 17 years. I enjoyed working for this great man. He was very loyal and fair to all his employees. He was always there to listen and advise if you had any problems or difficulties in your life. Thank you for all these years. Mikko Niskanen |

|

I met WEM (as I called him) in 1995. It was a job that was to last one month. It went on for almost 16 years. He was the best--he was my friend as well as my employer and I enjoyed seeing the love he lavished on his projects just as my own father did, moving back and forth with the seasons between his houses in Northern California and Southern California. And shopping, shopping, shopping--until everything was just right! I am so happy to have been a part of all that to the end. I'll love you forever, WEM! Gina Ciken |

|

It's fair to say that he abused the waitress. Ellery and I were fellow members of the club at Meadowood. Once, quite a while ago, probably during the Meadowood Classic, several of us were having lunch at the grill and Ellery became very angry at the waitress. He had installed in the back room a personal bottle of French's Mustard - Meadowood is far too glam to carry French's - and was extremely miffed that the staff had lost it. It's fair to say that he abused the waitress, who was of course completely at a loss. He absolutely went off on her. The reason I bring this incident up is this: In an association of nearly twenty-five years, as friends off the court and as partners and opponents on the court, this is the only time I ever saw him lose his composure. While it is undeniable that he was a kind and generous man, I believe all his friends will recognize him in the mustard story. And more to the point, I don't believe he would be offended by me telling the story. He would laugh at himself, at his bad behavior, sheepishly and a little ruefully. He was a very good guy and he saw things clearly. RIP. Charlie Smith |

|

He found out I was a native Sacramentan. He was certainly a unique character, sporting a blazer and ascot, calm but judgmental, and certainly opinionated. When not in a blazer at a formal affair, he was nearly always dressed in his croquet whites. We became friends in the early 1990's, when he found out I was a native Sacramentan, and younger than most at that time playing his favorite game. He also "approved" of my history of being a Sacramento Bee newspaper carrier in my youth. Not long after our meeting at Meadowood and again at the San Francisco Open, Jerry Stark called me to let me know that Ellery had invited me to play in his annual Ink Grade Invitational Tournament. Jerry loved to give me grief about my strong concern about the amount of the registration fee and never let me live that one down. Of course, this was Ellery's tournament, and there was no fee. And what a tournament it was! Five days of pure joy shuttling between Ellery's property on the mountaintop at Ink Grade, and Meadowood Resort in the Napa Valley, arguably two of the most beautiful places to play croquet in the country, certainly on the west coast. Ellery always made the players feel at home, and pampered at the same time. There are many fond memories of the times at Ink Grade, including very close friends, wonderful and competitive play, wonderful courtside banter, great food, and of course the luxurious tent cabin accommodations scattered around the property. There was no detail left unattended, and Ellery's staff made the event seem effortless, when we all knew it was anything but. Some of my very best friends, including Ellery, I came to know well over the last 20 years or so at Ink Grade. I will miss him. We all will. John Leonard |

|

Ellery was the guardian angel of American croquet. In my early days with the USCA and CFA I used to feel a bit intimidated by Ellery. He was certainly a character on the court - with his floppy hat and knickers and the way he dragged his mallet along behind him on the court. At board meetings, Ellery had a way of keeping his thoughts to himself until after everyone else had their say on an issue…and then he would make one common-sense comment and that would usually end the discussion. Over the twenty-five years I knew Ellery, we forged a respectful friendship, and I enjoyed playing at his Napa home and being a part of the celebration of his many contributions to the sport at the President’s Award Dinner at the 2005 Nationals at Mission Hills. In many ways, Ellery was the guardian angel of American croquet. We will miss him dearly. Anne Robinson |

|

For love of the built environment. I first met Ellery McClatchy in 1981 with my late husband, Jack McMillin. We became very close, seeing him often both in Palm Beach and in New York. When our daughter, Wallis, was born, Ellery agreed to become her godfather. Ellery gave Wallis an architecture computer program when she was about eight years old, which began her love, like his, of the built environment. She went on to study architecture in college. Ellery was very proud of her and his role in shaping her choice of profession. When Wallis expressed an interest in learning to play croquet, Ellery gave her a membership at the National Croquet Center. She took lessons and became enthusiastic about the game. He invited her to his Ink Grade Tournament the last year he hosted the event. He came to the courts to watch her play and she won her game! That was the only complete game Ellery watched, and he was so pleased for her. We will forever miss Ellery and the important role he played for so many years in our family. Barbara McMillin |

|

"Thanks for your fund-raising efforts." That was the under-stated public acknowledgment for what Ellery ACTUALLY did for the USCA and CFA in 1995-1996 - which would be more accurately described as a bail-out. I was the bookkeeper for both organizations for Accounts Payable, Salaries, etc. Ellery said to me, "Let me know what you need and what it is for." I would send the monthly bills to him and he would write a check. When it came to croquet, nothing was too much for him. Shereen Hayes |

|

| Ellery croqueting on his Ink Grade court. Peterson photo. |

|

I met Ellery during a tournament at PGA. It was the old croquet headquarters in Palm Beach Gardens. Someone asked me to go out and keep the boards with Ellery. I went, introduced myself and kept the boards with him - one for striped, one for solid. Later someone told me Ellery mentioned to them that he liked me. His reason? I didn't talk. In all the following years when Mike and I became close to Ellery, I noted that he was careful about what he said. So when he spoke, people listened. He was careful in the clothes he chose to wear. He was careful in creating special living environments. His creativity, his humor, his intellect all had quiet ways of being expressed. We will miss his generosity and his dignity. Cynthia Gibbons. |

|

Ellery was Osborn's Secretary of State. When he died, I was in the middle of doing what I could to get Jack McMillin, founding president of the Croquet Foundation of America, nominated for the 2012 CFA Hall of Fame. I was happy to be able to tell Ellery that I thought McMillin would finally be acknowledged for his hard and good work with his wife Barbara as the founding president of the CFA. Ellery had been much involved in the formation of that organization because at that time he was living in Palm Beach and helping Jack Osborn on many projects and on many fronts. Some time after Jack and his wife Barbara had spent a lot of their own money and lots of time and effort traveling the country on a national tour to meet and welcome new players and clubs, Jack M. declined to do something or other that Jack Osborn wanted done. So Osborn essentially cut him off. Osborn did that a lot, and Ellery was the most likely person to patch up the damage to hurt feelings and bruised egos. To help make up for what he considered Osborn's mistreatment of McMillin, Ellery's biggest donation to the National Croquet Center was dedicated to Jack McMillin, now long deceased. You can see the dedication plaque to McMillen prominently displayed above the steps that lead out toward the center courts. Ellery wasn't sure the National Croquet Center was a good idea. "But I don't want to be a dog in the manger," he told me. So with that $100,000 gift, Ellery was doing his part to support an important project, and at the same time acknowledging an under-appreciated personal friend and fellow benefactor to the sport. Bob Alman |

|

"Keep doing what you're doing, because it's working." Ellery was a truly humble man. He listened quietly, got the idea, and spoke softly to help. Shortly after starting the Mission Hills Croquet Club in Rancho Mirage, California, 21 years ago, I was asked to meet him for lunch and discuss what I had planned for croquet. Dick Tucker, who know Ellery very well from their common interests around Carmel, New York, where they had both lived, set up the meeting, forewarning me of Ellery's stature in the croquet world. I told Ellery what I planned and asked for his advice. He said only, "Keep doing what you're doing, because it's working." I told him many times after that how he had helped me with those words. I was such a novice, and he had given me confidence to do something I had never done before. He approved of my insistence on attracting the best people and the best players. But the icing on the cake was when he moved there, bought a great place, and did it over so his home would accommodate many guests for croquet tournaments and be a fit setting for the best parties on the West Coast, at the Mission Hills Invitational, the US Open, the Presidents Cup, and many others. Jim Butts, our third president, told me Ellery also helped with donations for expanding the courts. We will probably never know the full extent of his private generosity. When Ellery found out that Merv Griffith had started a croquet club, Ellery donated a deadness board and became the first member. Ellery's unfailing support helped Mission Hills become the biggest US croquet club outside Florida. Thank you, Ellery! It's still working! Pat Apple |

|

I never met Ellery McClatchy. He never visited my home turf, the Pasadena Croquet Club. But he sure had a huge impact on our club. We started in 2006, borrowing space on a lawn bowling green. There was a patch of grass in the middle of our court that was basically a few blades of grass holding the dirt together. We badly needed to extend the sprinkler line to the middle of the court to fix that problem. Some of the croquet players visiting from other clubs referred to the middle area of our court as "the Pasadena desert." One of our club co-founders, David Collins, mentioned to Ellery during a tournament dinner at Mission Hills that we had just started a club in Pasadena and only had four members. David walked away from the conversation with $1,000 donation from Ellery. That money was put to good use in extending the sprinkler system and fixing our court. The "Pasadena desert" is long gone. We now have 21 members and host many tournaments every year. I'm a bit saddened that Ellery never got a chance to see how his gift was used, or that I won't be able to shake his hand and say Thank you, Ellery! Eric Sawyer |

|

The Ink Grade Invitational was no ordinary croquet event. Cynthia and I shared some of the great weeks of our lives with this kind and generous man at his home in Pope Valley, California, above St. Helena in Napa Valley - named "Ink Grade" after the family's newspaper business. Annually Ellery would gather his croquet playing friends from the West Coast and organize a croquet tournament with Jerry Stark as the director. This was no ordinary croquet event. Ellery’s "resort" was a home he created and built near the top of a mountain, with himself as the architect and the mountain as his canvas. He created beautiful gardens sensitive to the environment, with abundant fruit and fig trees, adding grape and olive vineyards on the sunny side of the mountain. His remodeled ranch house rambled on—all on one level with very spacious and interesting rooms and decks where we all gathered. The real treats were the friends he brought together, the outstanding staff that catered to our every need, and the food and wines. We enjoyed delicious food and wine at home, in magnificent Napa Vally restaurants and at glorious vineyards. All the players in the "Ink Grade" tournament were able to stay for a week on the property because Ellery strategically placed luxurious tents around the mountain and supplied golf carts for his campers. As NYC people, Cynthia and I stayed in the house because we are just not campers, period. Every morning we awoke to the most beautiful sun rises coming over the mountain and more marvelous than these, Ellery had arranged for a staffer to drive 50 miles each morning over the mountain to deliver the NY Times to us by 6:30am. Mike Gibbons |

|

That late-summer event was the most special week of the year. I first met Ellery through croquet at the 1989 San Francisco Open, when his doubles partner was Peyton Ballenger. Later that year I visited Ink Grade for the first time. Ellery hosted a dinner for the Sonoma-Curter World Championships when the grass seed on his new court was just sprouting. It was the following summer that the Ink Grade tournament tradition began. After the first year, the invitation was assumed on Ellery’s part, but Charlie Smith, Mike Orgill, and I never were quite sure: we would check with Ellery's staff to make sure we were expected to come. What can you give someone who provides such wonderful experiences year after year – for 20 years? A couple of cases of Smith-Madrone wine with custom "Ellery" labels became our annual gift for the Ink Grade tournament. The wine came from Charlie and Judie, and I would design and produce unique "Ellery" wine labels. That late-summer event was the most special week of the year for us--tenting it on Friday night, croquet and more croquet, friends and more friends.....Jerry Stark used to tell the story of John Leonard’s first year, when John asked about the entry fee. Jerry answered that it was Ellery’s tournament – John didn’t get it and insisted on knowing what the entry fee was. Thank you, Ellery, for the gift, and for including us in your vision. Ervand Peterson |

|

"Will you get this woman off me?" When I first met Jack Osborn at the Western Regionals in Seattle in the mid eighties I tried to tell him what we were doing on public courts in San Francisco. But he quickly dismissed me by saying, "Croquet in America is a sport for the elite class." Ellery agreed it was a good marketing strategy, because USCA croquet actually did attract that elite class in the beginning, and they were the people who could get courts built on their estates or at the country clubs or favorite resorts. But soon, precisely because Osborn's pitch was successful, everybody believed it was actually true, so as a consequence the most virulent species of social climbers quickly figured out that croquet would give them instant entree to high society. According to Ellery, the original supporters of the USCA maintained their support in the face of this onslaught, but soon retreated for their own protection behind the walls of their country clubs and private estates. However, as the most committed bridger of classes and purposes, Ellery often found himself in public venues oppressed by people--especially high-toned women--who desperately wanted to be his friend. One such occasion cemented my friendship with Ellery, who was already providing financial support to some of my projects. It was an evening event, there was a band, everyone was having a good time.....except Ellery, who was obviously miserable as one particular woman, smiling and chirping, clung to his side. When the woman was momentarily distracted, Ellery leaned towards me and said quietly, "Will you get this woman off me?" Ellery knew of my pathological fear of ballroom dancing; nevertheless, I asked the woman to dance with me, allowing Ellery to beat a retreat. It was the only personal sacrifice I ever made for Ellery, and I know he appreciated it. Bob Alman |

|

Ellery and I were friends for many years before croquet. It was perhaps an omen of things to come that the first present I gave him – in 1966, I think – was a croquet set from Abercrombie and Fitch, so we could play croquet on the sand at his house on Fire Island. That was, of course, the old game, with lots of cheating and dragging of feet to create a path for the balls to follow. More than a decade later, I took up the game while at Stanford for a year, and – having bought a Jacques set – attracted the attention of Jack Osborn and the New York crowd when I stayed with Ellery in the summer of ’79. I played croquet in Central Park, learning from Teddy Prentis in the expectation that when I returned to Boston, I would be able to start a club there. Ellery decided to come with me to a "croquethon" that fall in New York, and after that, it was all over. He went back home that evening and began making plans to blast out the koi pond and create a croquet court. I returned to Boston, started the club, and several of us came down every year for our annual tournament at his house. He went into the city himself then to take lessons from Teddy, and Ellery and I traveled on the croquet circuit to Palm Beach and Bermuda, Arizona, Illinois, and even to visit Francis Tayloe in North Carolina, returning for the opening of Pinehurst.

After a few years, Ellery decided his court wasn’t good enough, so he blasted out a good part of the hillside, then built it up again, and – at great personal expense – produced the most beautiful, smooth, and even court I’d ever seen. We had one tournament, and he concluded there weren’t enough people in the area to play croquet (although neighbors included my sister Mimi, Maryholt Maxwell, and Dick and Martha Tucker). Shortly thereafter he sold the house and moved to Palm Beach. The more engaged in croquet he became, the more he came into his own as a quiet but strong supporter, mediator, and friend to many players around the country and the world. One of his earliest forays was to the Palm Beach Croquet Club, where he joined the social committee for the tournaments - which would guarantee his getting a table as far away as possible from the band. He had a great time and grew with the organization. He supported my efforts with collegiate croquet, underwriting the booklet I wrote called "Basics of Croquet" that included both the American and Association games (a definite no-no during the "croquet wars" in the 1980s). He supported clubs and individuals who were devoted to the game. Building on that experience, he also came to play a critical role in his family and the family business as the quiet listener and mediator who could see things from both the inside and the out. He was a constant friend to many, but the most constant for me. Xandra (Sandy) Kayden |

20 September 2011

Nottingham List Death Announcement

by Bob Alman

Ellery McClatchy passed away at his mountainside Ink Grade estate in Pope Valley, California, on Tuesday morning, September 20, 2011, at the age of 86. He was found early in the morning by his Mikko, his longtime assistant and chef.

He had been taken to a local hospital over the weekend with breathing difficulties which appeared to be eased, so he requested to return home on Monday. His nephew Kevin will handle the funeral arrangements for a family burial in Sacramento.

Ellery was the last surviving member of his generation of owners of the largest privately held newspaper chain in America, started and headquartered in Sacramento, California. He was an active member of the McClatchy board to the end of his life, and his wisdom and experience were highly valued by his family and the officers of the McClatchy chain.

Although the cause of death has not been officially announced, the immediate issue was emphysema, exacerbated by other medical problems. He had been on oxygen virtually full time for several years, learning to move around his home tethered to plastic tubing with which he had learned to navigate expertly through his personal domains, in both the Northern California house and his winter residence at Mission Hills Country Club in Rancho Mirage.

A risky operation in Orange, California in the nineties which removed nonfunctioning lung tissue in order for new and healthy replacement tissue to grow gave him more than a decade of extra life, enabling him to live in reasonable comfort to the age of 86.

When I visited him for a week at his Mission Hills home in February 2011, I was impressed with the way he had organized his life. Even in his condition, he was a most generous and gracious host. He even insisted on throwing a dinner party and asked me to invite whomever I pleased. Mikko and his staff prepared and served a sumptuous feast, which Ellery seemed to enjoy as much as any of the other five people at his table.

Ellery McClatchy was my long-time personal friend and patron. He made it possible for me and many others to do what we wanted to do to help build the sport, often insisting that his financial support be held in absolute secrecy.

Ellery was a strong pillar in the foundation of the USCA from the early 80's, moving to Palm Beach and helping USCA founder Jack Osborn in countless ways get the unlikely national association off the ground. His help was given not just in the form of financial support but also as wise counsel. He helped Jack Osborn found the Croquet Foundation of America and enlisted its first president, Jack McMillin. Subsequently Ellery himself served two terms as CFA president.

As others came and went - often in bitter disputes with Osborn over many issues during the growing pains of the croquet entities - Ellery's support to the sport was constant for more than 30 years, not just to the USCA and the Croquet Foundation of America, but to many individuals and clubs throughout America.

The full extent of his charity may never be determined, but I can personally attest to his generosity in helping the San Francisco Croquet Club get well started; and he donated $1,000 to help the Oakland club with its initial equipment stock. He was always willing to donate dinners and other social events for USCA tournaments in both Northern and Southern California. His Ink Grade Invitational was, perhaps, the most elaborate and elegant annual ever seen in the sport - but in the typically relaxed and low-key, understated style that was Ellery's hallmark.

When I asked Ellery for a grant to support the further development of the USCA website and Croquet World Online Magazine in 1997, after they were both started and their value was evident, that grant more than paid for essential programing and redesign which positioned them as the best croquet websites in the world at the time. When I moved to West Palm Beach to organize and manage the National Croquet Center in 2000, I called to thank him for all the support he had given me; and he told me he would continue the grant because he liked the work I was doing. This grant was sustained until just a couple of years ago when the rapid decline of newspapers had radically affected his budget, and with apologies, he reluctantly ended the monthly support.

There has never been anyone like Ellery McClatchy in the sport of American croquet. He was an original who cannot be replaced.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Mike Orgill and Bob Alman are classic "croquet buddies," having met on a corporate writing project in San Francisco in the 70's and organized the San Francisco Guerilla Croquet Club, which regularly invaded, with Mike's wife Helen and a small coterie of friends, such forbidden ground as military bases, private estates, and corporate headquarters to set up and play nine-wicket croquet. They always got away with it because in their all-white duds, they looked authorized. It was Mike who suggested to a reluctant Bob in the early eighties that they should join the USCA. (Bob thought the games on half a hilly putting green in Stern Grove looked far too serious.) It was also Mike who brought Bob into the lively but short-lived Croquet Magazine venture with Hans Peterson in the mid eighties - a black-and-white glossy which was the precursor to Croquet World Online ten years later. Mike and Bob organized and managed on the notorious "San Francisco Hill Course" the first of sixteen editions of the San Francisco Open, which ultimately grew to seven lawns and 64 players. They partnered in several early B flight victories in the Western region. As long-time president of the SFCC, Bob event-managed several regional and national USCA tournaments in San Francisco and struggled for years to get the Oakland Croquet Club started on the bowling greens across the bay. Bob moved to South Florida in 2000 to organize and manage the National Croquet Center. Mike became the president and chief event manager of the Sonoma-Cutrer Croquet Club in the 1990s and more recently has established himself as one of the leading players at the Mission Hills Croquet Club in Rancho Santa Fe; In 2012, Mike will succeed Rhys Thomas as the USCA's representative on the World Croquet Federation's Management Committee. Bob and Mike were both long-time friends of Ellery McClatchy as well as recipients of his generosity in countless ways. As this article shows, they still enjoy partnering in worthy croquet ventures.