|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| News & Features |

|

Who Really Won the Election of 1876?

|

||||||||

|

by Mike Orgill and David Drazin Spiegel Grove photos by Mike Orgill Posted November 2, 2008

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

There's a reason the fourth Republican president, more than any other American politician, is identified with croquet. His Democratic opposition blasted him for the spending of public funds for private purposes. Their prime proof? The extra six dollars he spent for boxwood balls for his croquet set. Rutherford B. Hayes is most known for his dubious victory in the election of 1876, an election so contentiously contested that he took the oath of office in secret to reduce the danger of rioting in Washington, D.C. Historians now agree that Hayes got a bum rap and performed responsibly and well in office. Is a fondness for croquet more conducive to a "presidential temperament" than playing golf or shooting quail?

A popular Republican governor and a Democratic reformer battled to a draw in a nasty presidential campaign. The electoral college vote verged on a tie, and the win depended on a disputed voting process in Florida and other states.

The nation was paralyzed; angry demonstrations sprang up; campaign surrogates rushed to the disputed states; a cascade of lawsuits engulfed the courts. The worst constitutional crisis in decades threatened to destroy the nation's faith in its political institutions. The crisis gripped the nation for months. It seemed that leadership on all levels had failed.

Was this the election of 2000 when Governor George W. Bush of Texas faced Vice President Al Gore? The election debacle in Florida with its hanging chads and accusations of voting fraud? Was this when the United States Supreme Court intervened and "selected," as the Democrats charged, George W. Bush as President?

|

| Rutherford Birchard Hayes (October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) the nineteenth President of the United States (1877–1881) |

Only eleven years since the Civil War, the United States still suffered from sectional division and systemic corruption. The Republican party had almost total control of the government since 1865, dispensing patronage and administering the reconstruction of the South with an iron fist. The scandal-racked Ulysses S. Grant administration was the first two-term presidency since Andrew Jackson. Historians rank Grant as one of the worst presidents, largely because of his inability to control corruption.

The scandals included Black Friday, when Jay Gould and Jim Fisk attempted to corner the gold market; the Whiskey Ring, in which Grant's private secretary was implicated; and the Credit Mobilier scandal, a railroad contract-rigging conspiracy.

Grant was never implicated in any scandal, but his inability to control his administration and his seeming blindness to the criminal activities surrounding him enraged his many critics.

Southern states seethed under the administration of radical Reconstruction. The U.S Army propped up Republican party rule in occupied southern capitals. The election of 1876, with two non-incumbents vying for the presidency, was a referendum on the U.S. Government.

The Republicans stood for centralized power and claimed credit for preserving the Union. The GOP believed in free market capitalism and boasted that they alone would protect the civil rights of the blacks freed by the blood shed in the Civil War.

The Democrats decried the scandals of the Grant administration and made these breaches of trust the central argument for shrinking the government and instituting broad reforms. For the Democrats, the abuses of radical reconstruction mirrored the corruption in Washington. Returning rights to the states was the way to reform. The end of Reconstruction would mean the rebirth of the Union.

The Democrats nominated Samuel J. Tilden, the Democratic governor of New York. Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican governor of Ohio, was the Republican compromise nominee. Both nominees were well-respected, accomplished men. An aura of stability surrounded each candidate. Tilden and Hayes were fiscally conservative and were regarded as reformers with few hints of scandal in their backgrounds. Following nineteenth century campaign etiquette, neither candidate campaigned in the modern manner; Tilden and Hayes surrogates fanned out across the country to prospect for votes.

By twenty-first century standards the candidates of 1876 were far from charismatic.

Rutherford B. Hayes was a war hero as well as an honest and capable governor. But a charmer like Bill Clinton or Ronald Reagan he was not. About Hayes, The Nation complained: "No ingenuity of interviewers was sufficient to extract from him any expressions of opinion on any topic having the remotest bearing on the presidential contest. He recognized nothing and neither authorized or repudiated anybody. He would hardly go forward . . . than to accede to the proposition that there was a republican form of government and that this was the hundredth year of the national government."

The acerbic writer Ambrose Bierce, who served with Hayes during the Civil War, wrote: "Hayes is only a magic lantern image without even a surface to be displayed upon. You cannot see him, you cannot feel him."

A strong reformer, Samuel J. Tilden dismantled the Tweed ring. He was a brilliant political and legal mind but perhaps the most reclusive and bookish presidential candidate in American history.

A New York Herald reporter visited Tilden's home town to unearth colorful details about the governor. The reporter failed: "No one remembered his robbing an apple orchard, or running away from school to go swimming, or playing hooky to go fishing, horse racing, hiding his grandmother's spectacles or indulging in any other pastimes for which country boys are noted all over the land. He enjoyed his sports and studies, was a good mathematician, the model of his teachers, and the admiration of his fellows." Tilden, in other words, was a nineteenth century nerd.

The body politic was polarized

The 1876 body politic was badly polarized, but no one was prepared for the crisis that erupted.

Tilden won the popular vote with 250,000 more votes than Hayes; he garnered approximately 350,000 more votes than the entire field which included three minor candidates. In the all-important count of the electoral college, Tilden seemed to lead 203 to 166. Only 185 votes were needed for victory. Hayes went to bed on election night convinced that he had lost.

Most newspapers concluded that Tilden was the new president, but two Republican-leaning New York papers refused to give in. The Times trumpeted: "A Doubtful Election"; The Herald mused: "Something That No Fellow Can Understand. Impossible to Name Our Next President." Spurred by the Times and die-hard Republican operatives, the Republicans refused to concede. They claimed that the returns from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina were suspect, that blacks were being kept from voting, that the ballots were confusing and that widespread voter fraud was apparent.

Scores of political operatives from both parties rushed south to "oversee" the counting of ballots. Demonstrations and mayhem followed. For the first time since the Civil War it seemed possible that sectional violence would tear the country asunder. The lame duck President Grant ordered the army to surround the capital and guard the bridges and roadways leading to Washington, D.C.

To their credit, both Hayes and Tilden refused to enflame the situation. But Hayes, although placid on the surface, was a shrewd political operator. His surrogates worked behind the scenes to secure the election. Tilden became strangely passive, retreating to his study to write legal briefs supporting his position, frustrating his supporters who wanted him to take a more assertive role.

The country paralyzed in constitutional crisis

The constitutional crisis paralyzed the country for three months. Anxious to resolve the crisis and avoid civil war, Republican and Democratic leaders met in secret. They agreed to support the congressional appointment of a special Electoral Commission to resolve the election. Comprised of five senators, five congressmen, and five Supreme Court justices, the commission on the surface seemed a model of fairness. But since the justices were Republican (an independent justice was supposed to serve but dropped out at the last minute) the verdict of the commission was pre-ordained.

Why did the Democrats, with a seemingly strong position, agree to this plan? In a secret deal, the Republicans assured their opponents that upon Hayes's victory troops would be withdrawn from the South, local southern state houses would revert to Democrats, and future Democratic control of the South would be ensured. Thus the "selection" of Hayes in the 1876 election brought an end to Reconstruction, effectively closing the books on the conflicts engendered by the Civil War. The "Compromise of 1876" set the stage for the reign of "Jim Crow" in the former Confederacy.

[See an in-depth article on the election of 1876 on the Hayes Presidential Center's website.]

The Hayes presidency: a model of probity and stalemate

The election brought Samuel J. Tilden's political career to an end. Rutherford B. Hayes announced that he would be a one-term president and kept his promise. After the Grant administration, the Hayes presidency was a model of probity. Hayes attempted to reform the civil service but since the congress was largely in Democratic hands, his initiatives went nowhere. Hayes called attention to the plight of freed slaves in the South, but his Faustian bargain ending Reconstruction made his word, although heartfelt, seem hollow. Hayes was fairly popular when his administration ended, but he refused all Republican entreaties and kept his word that he would not seek another term.

|

| Spiegel Grove is the 25-acre estate in Fremont, Ohio, to which President Hayes and his wife retired after his four-year term as president. This 31-room house is the centerpiece. |

Before retiring to Spiegel Grove, their estate in Fremont, Ohio, Hayes issued his last executive order, which banned alcohol sales at army posts. His wife, later known as "Lemonade Lucy" for the non-alcoholic dinners she hosted, must have been pleased.

The American croquet connection

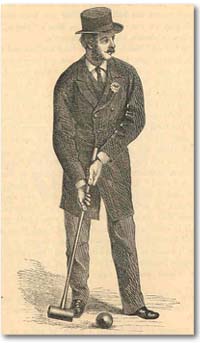

No one knows precisely when croquet first came to North America. When it broke out of its birthplace in Ireland as an upper-class diversion in the 1850s, it was so transportable that it could have been carried anywhere, and probably was. That it forged ahead with such vigor in Britain was very largely due to the mania of one enthusiast, Walter Jones Whitmore, who introduced it to his many friends and followers, and then propelled it to dizzy heights as a contest of tactics and supreme skill.

|

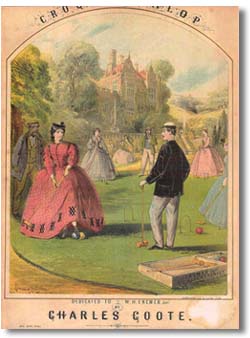

| The mutiple pleasures of social croquet in the post Civil War era are illustrated in the sheet music cover illustration for "Croquet Galop," 1866. |

The Civil War had a lasting impact on the distinctive character of American croquet. While the men folk were slogging it out on the battlefield, the game played on the home front marked time while gigantic advances were being made on the other side of the Atlantic. So America was not ready for the Field Laws of 1866 or the Conference Code of 1870. And while the establishment of the All England Croquet Club in 1868 marked the origins of an authoritative law-making body in Britain, America just looked the other way.

|

| This figure illustrating first position for the two-handed stroke is taken from Whitmore's "Croquet Tactics," 1868. In an era long before short-grass courts were common, the full backswing and follow-through in the two-handed stroke produced the power needed to navigate rough turf. |

The spirit of American croquet played during Hayes's presidency was well captured by the literature and visual arts of the period. From about 1860 croquet was portrayed as a fashionable pastime by an increasing number of writers: Holme Lee in Sylvan Holt's Daughter (1858), Charlotte Yonge in The Trial; Or More Links of the Daisy Chain, Anthony Trollope in The Small House at Allington, Louisa May Alcott in Little Women, and Lewis Carroll, to mention but a few. Though Carroll's masterpiece Alice's Adventures in Wonderland did not appear until 1865, he first told the story to the daughters of the Dean of Christ Church College, Oxford, on July 4 1862. Long celebrated otherwise by most Americans, real Carrollians can only think of that day as Alice in Wonderland Day.

Croquet was also well represented in the visual arts. Winslow Homer, Degas, Manet, Bonnard, and James (Jacques Joseph) Tissot all depicted croquet in their grand oil paintings, and Winslow Homer added some fine engravings. But the aspirational aspect of the game, so dear to the hearts of would-be players, was presented most powerfully on the covers of the sheet music of the day, prominently in the work of an English illustrator, Alfred Concanen.

Croquet in the Hayes White House

We know of croquet in the Hayes White House chiefly as the Achilles heel of a president perhaps justly celebrated for his claim to the moral high-ground. With a strong taste of sour grapes, in 1880, very soon after the conclusion of his four-year presidency, a Democratic Committee took him to task for feathering his nest at the taxpayer's expense.

|

| Co-author David Drazin examining croquet materials at the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library. The Rutherford B. Hayes Center houses the Presidential Presidential Library and archives, including the Rendell Rhoades Croquet Collection. Co-authors Drazin and Orgill are among the very few members of national croquet organizations to examine the archives on site. |

Of course, as we learn from Professor Rover's manual, The Game of Croquet: Its Principles and Rules, perhaps the leading American introduction to croquet of its time, there was nothing special about boxwood balls. They were inclined to be brittle and by no means especially favored. Boxwood was just one among several acceptable materials used for the purpose.

Proving a negative proposition is always fraught, but there is no evidence that Rutherford himself was a committed croquet freak in his White House years. The game was just an amusement available to his family and staff, as it had been at his home at Spiegel Grove.

|

| We can easily imagine croquet being played on the commodious grounds of Spiegel Grove, as the hugely popular game was played in all English-speaking countries in the last half of the 19th Century. But, alas, we have yet to find pictures to prove it. |

|

A Hayes Presidential Center Treasure: The Rendell Rhoades Croquet Collection |

|

The Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center at Spiegel Grove now boasts a superb research library. Among its many treasures is the Rendell Rhoades Croquet Collection, assembled by Rendell Rhoades, a croquet enthusiast and academic marine biologist. The collection consists mostly of several hundred books and pamphlets about croquet or referring to it, all beautifully conserved and indexed, and available at short notice for study in agreeable surroundings. Rendell Rhoades was fortunate to have married a professional librarian, Nancy L Rhoades, who described the contents of the collection in Croquet: An Annotated Bibliography from the Rendell Rhoades Croquet Collection. On his death in 1976, she had several collections to dispose of, including seven thousand crayfish preserved in formaldehyde.

|