|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| Letters & Opinion |

|

Unsolved mysteries of croquet history

|

|||||||||||||

|

by David Drazin

layout by Reuben Edwards Posted October 25, 2004

To comment or respond to the author’s request for historical information,

visit Croquet World Online’s History Forum

|

|

||||||||||||

History and bibliography are two sides of the same coin. So it’s no surprise that the author, who published the first definitive bibliography of croquet in 2000, should have become World Croquet Federation Archivist/Historian and turned his attention to the history of croquet. In this account of some of the unsolved mysteries he has uncovered, David Drazin invites our help in piecing together the past through the online History Forum so we can understand what has shaped the game in its various forms as it is known today in different parts of the world.

Anyone curious enough to look into the history of croquet might get the impression that the subject has been sewn up, that the main lines of evolution of equipment, rules, techniques, and administration etc are clearly documented, and that the claims to fame of the makers, shakers, and star players are well established. But look a little more carefully, and you will see that it is not quite like that. While many writers have detailed the history of particular clubs, associations, events, and laws, and the biographies of personalities, the bigger picture is very patchy. David Prichard’s The History of Croquet , published in 1981, is a superb book, but it was written over 20 years ago and says nothing about roque, gateball, or golf croquet, and very little about the development of the game outside the British Isles.

There is an awful lot that we don’t know, so the task of compiling an up-to-date definitive worldwide history of the game still beckons. Until recently I had planned to do just that in collaboration with a team of like-minded historians from the principal croquet-playing countries of the world. But, sad to say, our publisher lost his nerve. Maybe the managing editor was reluctant to invest company funds in a book that would take time to research and might have limited appeal on world markets.

But nature abhors a vacuum. Sometime someone, perhaps a croquet insider with good connections in the publishing world, will hit on the right formula to tell the world the true story of the Queen of Games. Judging by our experience, whoever rises to the challenge will receive enthusiastic support from informed croquet lovers all over the world.

Some macro-mysteries

Meantime, here are some missing pieces of the jigsaw that may serve as targets for historians who have access to relevant sources that have hitherto escaped attention. Let us look first at some mighty macro-mysteries — mysteries relating to matters that had, or may have had, a profound long-term effect on the evolution of the game of croquet as played in various countries and regions of the world.

In the beginning ...

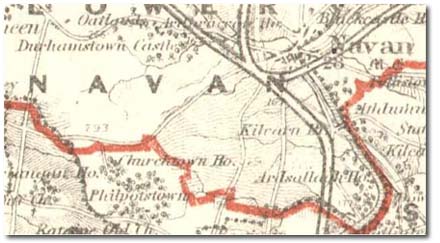

Perhaps the biggest unsolved mystery is how the game evolved in the beginning. The fact that it was played in Ireland in the early decades of the nineteenth century is well attested by correspondence published in The Field in the 1860s, but we have no documentary evidence whatever as to where and by whom, and how the game originated. We have some excellent clues. The first reports of croquet being played in Ireland that appeared in The Field in 1858 were of meetings held at three country houses outside Navan, County Meath, not far from Dublin, and later reports tell of events at other prominent houses. Recent inquiries at these locations have failed to unearth promising leads, but there are good grounds to expect a breakthrough. Social functions were well covered at the time by local newspapers, which are preserved in local libraries and national collections. Anyone with the patience to leaf through these old journals could well discover an account of how someone came up with the novel idea of striking one ball while in contact with another. A good place to start would be the British Library Newspaper Library in Colindale, north London, which claims to have the largest collection of Irish newspapers in the world.

|

| Map of Navan environs, County Meath, Ireland, showing earliest croquet venues: Oatlands, Durhamstown Castle (‘Dormstown’), Philpotstown. Source: Report of the Boundary Commission for Ireland 1885 |

False starts in the US

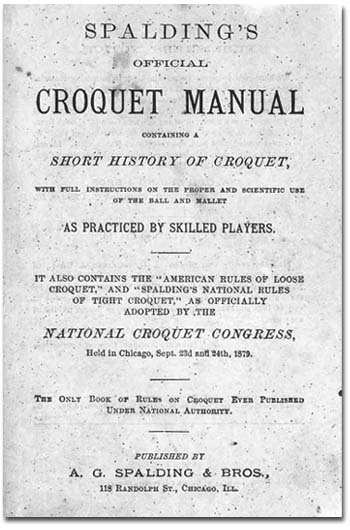

The development of croquet in America presents all sorts of puzzles. Perhaps the most remarkable is why it took so long to form an enduring national governing body. The game came to North America in the early 1860s, but it was only in 1977 that Jack Osborn founded the USCA and then succeeded in establishing its authority nationwide. Hence the American Rules we have today. But it might well have been different. There had been previous attempts to found national associations, and other regional associations might have evolved into national associations, but none endured. The first task that these bodies addressed was to agree a universal code of rules, and we know of their existence by the rulebooks they endorsed.

|

| Title page of Spalding’s Official Croquet Manual (1880), ‘the only book of rules on croquet ever published under national authority’ |

Next to nothing is known about these early strivings for unity and authority. Who were the people behind these initiatives, what were their goals, and why did they not succeed? Will someone find the answers to these questions before the scent goes cold?

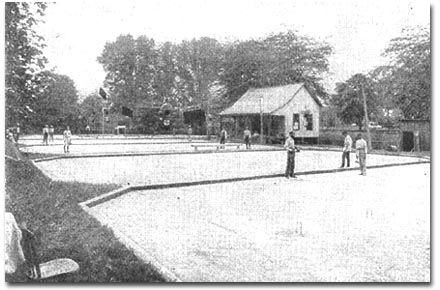

The rise and fall of roque

Exceptionally, the National American Croquet Association, founded in 1882 and later known as the National Roque Association, very nearly succeeded in establishing an enduring national following. Indeed, at its zenith between the world wars, many informed observers may have viewed this association as the one and only official national American croquet association. While some may have acknowledged that the game it governed was not quite croquet, in the absence of competition from a strong body representing the traditional game of lawn croquet it continued to make impressive progress. Until, that is, something happened that sent it into terminal decline.

Just recently Jack Roegner, President of the American Roque and Croquet Association, told me that his organization had to suspend tournaments because the number of participants at the Nationals had shrunk to single figures. The history of roque remains to be told. Its demise is no doubt due in part to the greater appeal of play on grass than on a prepared hard court. But I suspect that is only part of the story. A tour through the association’s recent yearbooks leaves the impression of a governing body that somehow lost its way. How this came about I would dearly like to know.

|

| Grounds of the National Roque Association at Norwich, CT. Source: Spalding’s Official Roque Guide (1902) |

Carry-over deadness in American Rules

Though scores of rule books were published in the USA in the nineteenth century, I have only seen two which imply that a ball remains dead on another until it has scored a hoop point, even in a new turn. How then did the principle of carry-over deadness come to be adopted when American Rules were formulated by the USCA? We know from such accounts as that given by Harpo Marx in his 1961 autobiography Harpo Speaks that carry-over deadness was observed by high-profile players on the East Coast in the early 1920s, and it is reasonable to surmise that the charter clubs of the USCA followed their lead. But two bits of the jigsaw are still missing. How did carry-over deadness, which was contrary to popular American practice, originate in the first place? And who influenced the rule makers of the USCA charter clubs to adopt it?

|

| ‘George S Kaufman plays a sticky wicket. The character in the background obviously suspects he’s trying to cheat.’ Source: MGM Photo by Durward Graybil in Harpo Speaks (1961) |

As to the early origins of carry-over deadness, we may have a clue in Rule 10 of one of the deviant rule books, Rules and Regulations for Playing Field Croquet , which went through several editions from the late nineteenth century and which may have been taken up by minority groups of players throughout America.. This rule states, ‘No ball except a rover can croquet the same ball twice, until the croquet has passed through an arch or hits a stake’. My guess is that the author or compositor simply omitted the words ‘in each turn of play’, not intentionally but inadvertently. These words recur in other rulebooks, but their significance may not have been apparent to the publishers. Croquet rulebooks of the period were a commercial commodity: it is evident that few were compiled by writers who had any understanding of the game.

Another possibility is no less plausible. Most of the early rulebooks were so incoherent that many players must have misconstrued some of the rules or invented their own to resolve ambiguities. These are only guesses. We may never know the truth but in our ignorance it is salutary to know that we don’t know.

|

| Front cover of Rules and Regulations for Playing Field Croquet by ‘Professional Players’ (circa 1880) |

We may have better luck tracing the line of succession from Harpo Marx and his buddies in the 1920s to the USCA charter clubs founded later in the century. We may not hear much these days of their founding fathers, but we can be reasonably sure that a few would be willing to share with us their recollections of how they first came to frame their rules.

The French connection

Croquet players in the English-speaking world have never taken French croquet seriously. The conventional view — outside France, that is — has been that the French themselves have never taken the game seriously, that it has always been a fun game played mostly on the beach and by young children. But there must be more to French croquet than meets the eye. The available literature is tantalisingly thin. I have been able to find only four titles that illuminate a remarkable renaissance of the game in the early 1890s: Stratégie raisonnée du croquet français [1892] by André Després, an advanced treatise on croquet tactics, Règle du jeu de croquet admise par la Société Française du Jeu de Croquet et l’Union des Sociétés Françaises de Sports Athlétiques , the official rule book of the national governing body, published at least during the period 1895–1910, Almanach Hachette (1898), which features the leading players of the time, and Les Tablettes Sportives [1912], which lists the winners of principal national events during the period 1894–1910.

And of course we know that, for want of overseas competition, local players made a clean sweep of the medals in the croquet events at the 1900 Paris Olympic Games. André Després, Ingénieur civil des Mines, Président de la Commission de Croquet de l’UFSFA, Président de la SFJC, was obviously a key figure in the development of French croquet, but that is about all we know of him. We have a few trees. All we need now is to see the forest.

|

| Henri Moullé, French Croquet Champion 1896. Source: Almanach Hachette 1898 |

The origins of golf croquet

Golf croquet is now well established on the world stage, but we know very little about its early origins. The first account I have found of a croquet-golf hybrid game is The New Game of Croquet-Golf: A Game for Garden Parties , published by FH Ayres, London, a leading sports good manufacturer, in 1896. And other proprietary variations on the same theme appeared in the next twenty years. All of these games were trivial because each player had a single ball or, if played as doubles, the partners played the same ball alternately, so there was precious little scope for tactics.

Golf croquet as we know it today — between two sides, each playing with two balls, calling for tactics as well as skill — seems to have been born shortly before WW1. But the identities of its parents and the circumstances surrounding its birth are a mystery. The first references to it in The Croquet Association Gazette , the official organ of the [British] Croquet Association, are in advertisements and brief reports of informal events held at official tournaments in 1912. Piecing together gleanings from these sources, we gather only that the game achieved instant popularity, that it was played according to rules compiled by Robert Leetham Jones, editor of the Gazette, and that Mr JEH Lomas and a mysterious ‘Professor C-S’ were widely recognised as authorities on the tactics of the game. My guess is that Professor C-S was Horace Francis Crowther-Smith, who published the first book on the subject, How to Win at Golf-Croquet , in 1913. But who exactly invented the game is unclear.

Until very recently, when the MacRobertson Shield countries came to appreciate that golf croquet offered unique opportunities for development, it always played second fiddle to association croquet. The rules were not officially recognised until 1934 and remained frozen in much the same mould until 1998, when the World Croquet Federation, responding to advances introduced in Egypt, launched a radical update on the occasion of the third WCF World Golf Croquet Championship at Leamington Spa, England.

Egyptians have dominated the WCF championship since its inauguration in 1996. But how and when they took up the game we can only guess. Croquet had been played at the Gezira Club in Cairo from the turn of the century; and we know from a brief contemporary report in The Croquet Association Gazette that visiting servicemen from the UK played golf croquet there during WW2. Perhaps the resident membership, inspired by the example of their visitors, appreciated the potential of golf croquet and thereafter gave it pride of place over association croquet. Or, as was reported in a recent article in The Guardian newspaper, their conversion to golf croquet may have arisen in similar circumstances twenty-five years earlier during WW1. Croquet World Online Magazine offers unrivalled facilities for the exchange of historical insights. We may hope that a member of the Gezira Sporting Club who has all the answers will enlighten us in the forum linked to this article.

East is east and west is west ...

The nineteenth century saw the diaspora of croquet. Requiring only simple equipment, travellers from Great Britain and Ireland took it wherever they went, and visitors from all over the world who had been introduced to the game in the UK took it back home with them. So there is plenty of documentary evidence that the game of croquet as played in Europe had reached Japan and China many years ago. How is it then that gateball, a team game played with similar equipment, came to supplant the traditional version of croquet in popularity? I dare say that the history of gateball is already well documented in another language. Let us hope that a multi-lingual visitor to Croquet World Online Magazine who is familiar with the story will come to our aid.

And now some micro-mysteries…

Mystery is the essence of history and bibliography. Every question answered raises others besides, so the more we know the more we know we don’t know. At the furthermost reaches, the questions that tease may be of little import in the grand scheme, but they are no less fascinating. Here are just a few.

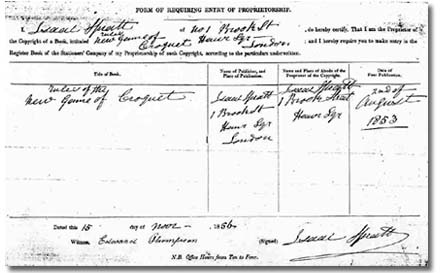

Isaac Spratt, begetter of the first code of croquet rules

In The History of Croquet , David Prichard tells us how Isaac Spratt, a London ivory turner, toymaker, and retailer, heard of the rules of croquet from a member of the Macnaghten family and committed them to print. That much is well documented, but the rules themselves are shrouded in mystery. The title Rules of the New Game of Croquet was registered by Spratt at the Stationers’ Company in London on 15 November 1856, the date of first publication being given as 2 August 1853, and there are three known references to the work in the contemporary press, but the rules they quote are at variance and no copy is known to have been seen since. So what can any of us do about it? Probably nothing but keep our eyes skinned for a surviving copy collecting dust somewhere.

|

| Signed form of entry at the Stationers’ Company of Isaac Spratt’s Rules of the New Game of Croquet. Source: UK Public Records Office |

And the origins of Spratt’s rules present other queries. Historians have long sought to identify his informant and the source of the rules told to him, but to date their researches have been inconclusive.

What’s in a name?

In the earliest reports we have from Ireland, the game of croquet was called ‘crookey’, ‘crokey’, or ‘crocky’; but, as we have seen, Spratt called it ‘croquet’ when he registered the title of his rules at the Stationers’ Company in 1856; and he may have used the same name when, as he asserted, he first published them in 1853. Did Spratt coin the new name himself, was that the name given to him when he first heard of the game, or did he get it from another source? If it was his own invention, he may have intended to follow the practice, which was fashionable at the time, of giving new games French-sounding names. If the name was given to him, it may have arisen from the understanding that the game was of French origin. We shall probably never know Spratt’s secret. He is long gone and we may presume he took it with him to the grave.

How the ‘e’ in croquet acquired a circumflex accent is more a curiosity than a mystery because the evidence points straight at John Jaques II, of the house of Jaques & Son, as the original perpetrator. On 16 July 1858, only a few days after The Field first referred to the game (as ‘croquet’), Jaques registered the title Rules and Directions for Playing Croquet — A New Outdoor Game at the Stationers’ Company, the ‘e’ in ‘croquet’ capped by a circumflex accent. Perhaps he adopted it in acknowledgement of the French roots of his own name. Others followed his lead on both sides of the Atlantic, but the circumflex accent, always recognised as an absurd affectation by language scholars, was short-lived. By 1875 it was all but extinct.

Captain Mayne Reid

The gallant Captain, native of Ireland and man of the world, is one of my favourite croquet characters, as he was of his contemporaries. If he had not been wounded in the Mexican War, I have no doubt that he would have gone on to play a prominent role in the American Civil War. And as a passionate republican, he might well have become the first post-war president of the US. As it was, he took time out in England, perfecting the new game of croquet, and is now best known as philanthropist, political orator, dandy, horseman, news publisher, poet, and celebrated author of romantic literature. To quote from his widow’s biography of him, ‘It was officially stated that “Mayne Reid is the most popular English author in Russia”; and you will find the whole of Mayne Reid’s works translated into French, Spanish, Italian, German, and for all we know to the contrary into Arabic, and the native tongue of the Red Indian.’ But not, I venture to doubt, his treatise on the game of croquet, the first book on the game to appear in the US. We know nothing about his dalliance with croquet except that he produced the first bestseller on the subject and successfully sued the sixth Earl of Essex for plagiarising his work. How he got into the game, where he played his croquet, and with whom, are mysteries we may never unravel.

|

| Captain Mayne Reid. Source: Elizabeth Reid, Captain Mayne Reid: His Life and Adventures (1900) |

Some mysterious noms de plume

Judging by the ubiquity of croquet noms de plume, one might suppose that croquet players are especially prone to reticence or discretion. Most correspondents who wrote to the editors of such journals as The Field, The Queen, Land and Water , and The Illustrated London News signed themselves by initials or noms de plume, and several of the earliest books on the game were anonymous or signed likewise. For many years the British Croquet Association permitted players in official tournaments to register under assumed names on payment of a nominal fee, and today several contributors to croquet notice-boards on the Internet identify themselves by cryptic Email addresses. All this is desperately frustrating for anyone who wants to know exactly who said what to whom. Here are just a few noms de plume from the age of crinoline croquet I would dearly like to crack.

|

| Front cover of Rules of the Game of Croquet [1862] by ‘G.V.H.’ |

The majority of rulebooks from the 1850s and 1860s were published anonymously or signed by initials or assumed names. Maybe their authors chose to remain anonymous out of modesty, not to imply originality. The first three would be my prime targets: Rules of the Game of Croquet (1862) by ‘G.V.H.’, The Laws of Croquet as Played by the Medes and Persians (1865) by ‘Rab-Mag’, and Croquet: As Played by the Newport Croquet Club (1865) by ‘J, “One of the Members”’.

The question is, ‘What is the answer?’

As the years go by, the mists of time thicken. Witnesses to happenings long ago pass on, memories fade, and documentary evidence gets scattered to the winds. So time is of the essence. If you can shed light on any of these mysteries, don’t keep it to yourself. Please ensure that it is captured for eternity by sharing it with others visitors to Croquet World Online Magazine .

An invitation to our online History Forum

Anyone may post feedback on any matter arising from this article on our Bulletin Board, simply by clicking here and following the menu. Select the History Forum category.