|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| The Game |

|

The complete story of carry-over deadness |

|

by Bob Alman

|

QUESTION: How is it possible to say anything new about the origins of deadness?

ANSWER: By bringing together many isolated facts turned up by scholars and academics and making reasonable conjectures which point to what probably happened--with a degree of certainty and conviction which would be beyond the responsible purview of a genuine scholar to declare in writing without shaming his profession. As a magazine writer, I suffer no such compunctions in offering this "exactly how it probably happened" narrative. According to me, it is a totally rational conjecture according with all the facts researched, uncovered, and recorded by the scholars and other "serious" but necessarily hampered investigators of the subject.

The influence of Herbert Bayard Swope, Jr. upon the establishment of the USCA in the 70's is well known and extensively chronicled. What has not been recognized until the last decade is that the weekend croquet marathons at the Swope place at Great Neck on Long Island in the early 20s--witnessed by the junior Swope as a child--set in place the most important distinguishing aspects of USCA croquet as we know it today. Without that influence, Jack Osborn may never have formed the U.S. Croquet Association, and the rules of the USCA game would likely have been much different and more aligned with Association Croquet as played in England and internationally.

|

| Herbert Bayard Swope would never have guessed that he would be credited with inventing the game promulgated by the United States Croquet Association almost two decades after his death in 1958. |

How and when the "official" games diverged

How the streams of development diverged across the Atlantic is a story of many dimensions, but we will deal with just one: the critical element of "carry-over deadness", which - I had heard ever since I started playing USCA croquet - was originally a part of the English game, long ago abandoned along with strict sequencing of the play of the balls (blue/red/black/yellow).

|

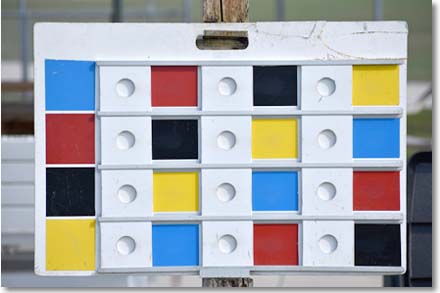

This photo from the Sarasota County Croquet Club shows everything you need to remember about this game: the state of deadness (all clean!), the clock on the post which has just expired, the clip on the blue ball to show that the blue ball is the first of four "last balls" in the final rotation after game time has been called, and the clipboard with score sheets on the bench, to record and report the result. (Is there any wonder that people call it "chess on grass"?) Photo by Sergio Nico. |

But this myth was exploded by the research of the late Dr. David Drazin of England, who was perhaps the premier expert and researcher on the history and development of the game, after Pritchard's comprehensive history, published in the 70's. Both experts would tell you that carry-over deadness was never a part of the game sanctioned by the Croquet Association or its forebears. Pritchard doesn't discuss it at all, and Drazin asserts that it may have originated as a proof-reading error in England for rules intended for players of garden croquet.

According to Dr. Drazin, "The earliest printing of carry-over deadness I have found is in Rules and Regulations for Playing Field Croquet, first published in England by 'Professional Players', circa 1900, and reprinted from time to time over the next 50 or 60 years. This may not have been the first rule book to prescribe carry-over deadness, but we can safely say that it was a rare aberration, perhaps a typographical error or editorial oversight."

|

| A typo in this British publication may have begun the chain of happenstance which finally resulted in official sanction for carry-over deadness. |

I have asked a half-dozen Association players in Britain whether they ever played carry-over deadness, and one of them, Croquet World co-editor James Hawkins, responded in the affirmative. Hawkins commented, "My family were playing with deadness in (I guess) the 50s and 60s (and possibly as early as the 40s). I remember the discovery of the phrase "per turn" in the late 70s, shortly after my introduction to the Association game. Drazin seems to contend that deadness had caught hold in the 1914-18 war. If Swope adopted it shortly after, it may have persisted [in England] for another generation, spreading via some oral tradition."

This excerpt from Drazin's ORIGINS OF CARRY-OVER DEADNESS explains how carry-over deadness may have persisted "illegally" outside the Association and learned by Swope Sr. in England, who then brought it to America in the early 20's.

"Swope Jr tells us that his father picked up croquet in England during the First World War when working in Europe as a newspaper reporter. Carry-over deadness was unknown in UK Croquet Association circles; but tournament play was frowned on by the British croquet establishment while the world was at war, and we know that Swope Sr was never a paid up member of the Croquet Association.. So it is possible that he picked up carry-over deadness, along perhaps with other aberrant rules, from British hosts who were unfamiliar with the 'Association' game. Or, having been steeped in the official Croquet Association game, seeing on his return home that that game would never wash among his new-found croquet friends in Long Island, he may have taken up carry-over deadness along with their mode of play."

|

| Part of the third interview with Swope Jr. in summer of 2005 included taking photographs at his Palm Beach home. This one is off the lanai, with Bob Alman on the left. |

A chaos of rules on both sides of the Atlantic

Swope's long sojourn in England coincided with the period in which the main elements of the "modern" Association Croquet game were still in flux. It's likely, then, that he learned to play "the garden game" there with a two-stake setting, perhaps in a double-diamond configuration.

According to Prichard, the "either ball" alternative was not introduced in the official rules of the Association until 1913 and not adopted exclusively until 1920. Experiments with the now-universal "Willis setting" were begun in 1904, but the single-peg, six-hoop configuration was not mandated until 1923, long after Swope had returned to America.

So the chaos of rules and standards in England around the turn of the 20th Century would have made it possible for Swope to learn any number of "wrong" rules to bring back to America. There's no reason to suppose that the same conditions of casual non-associated play in England did not resemble the traditional tenor of Backyard Croquet in America.

Every-weekend croquet at Swope's Great Neck mansion

|

| Winning the Pulitzer Prize for INSIDE THE GERMAN EMPIRE set the stage for the elder Swope's long and legendary career as a journalist at the New York World. |

Swope, Jr. recalls that his father brought back croquet equipment from England, but not the English rules. He is certain that they played carry-over deadness from the start, in 1922 at their house at Great Neck (they later moved to Sands Point) and he has no idea where the rules came from. Dr. Drazin is no help on this point: "Where Swope got it from remains a mystery we may never solve." (This was before Drazin discovered the tell-tale Field Croquet rules.)

|

| A great lawn ideal for croquet parties that often lasted well into the night fronted Swope's second Long Island mansion, at Sands Point--a tradition established at his first mansion at Great Neck. |

I have searched my own collection of ancient American-published rules - some provided to me by Dr. Drazin--and I can only confirm that carry-over deadness was not a part of any American games as revealed in all the popular printed version of the rules we can find from the beginning of croquet in America:

- Elisha Scudder's classic "The Game of Croquet", published in New York and Boston in the 1860's and subsequently revised and republished many times.

- Milton Bradley's, "Croquet, its Principles and Rules", published in the 1860's and republished and revised many times.

- "Spaulding's Official Croquet Manual" of 1879, published as a result of the proceedings of the National Croquet Congress of that year, held in Chicago, which gave players a choice of "tight croquet" and the in-contact croquet stroke played today.

In none of these classics does carry-over deadness appear in any form, confirming Dr. Drazin's thesis.

As soon as Dr. Drazin gave me in 1905 this "croquet scoop" about the origins of deadness in the American game, I knew I should meet Herbert Swope Jr. myself. At the time I interviewed him he was recently widowed and living right across the Intracoastal Waterway from me, in Palm Beach. In an extensive interview published in Croquet World Online Magazine, he confirmed that carry-over deadness was always a part of the croquet played at the Swope place at Great Neck in the 20's.

He didn't remember any set of printed rules of any kind--or any deadness board of any kind, for that matter. "They would have to remember the deadness," he told me. "They would have been insulted by the suggestion that they needed some kind of aid to remember." Of course this gave rise to frequent arguments, "but that was their style, that was part of the passion with which they played the game."

He didn't remember any set of printed rules of any kind--or any deadness board of any kind, for that matter. "They would have to remember the deadness," he told me. "They would have been insulted by the suggestion that they needed some kind of aid to remember." Of course this gave rise to frequent arguments, "but that was their style, that was part of the passion with which they played the game."

Another telling piece of evidence is this fact: Among all the many thousands of antique mallets and hoops and other croquet paraphernalia, there is not to be found one single deadness board or other kind of deadness aid predating the 1950's. By inference, the overwhelming popularity throughout croquet's development in the last century and to this day of eight-ball and now six-balls sets is further evidence that carry-over deadness was not widely played.

| HOW MANY STATES OF DEADNESS CAN BE SHOWN ON A DEADNESS BOARD? |

|

I asked my favorite Canadian mathematician to calculate all the possible states of deadness a board could show--not just for four balls but also for six and eight. Eight-ball sets were common in Britain in the 19th Century, and six-balls sets are the standard today for backyard or garden croquet. Louis Nel responded with these numbers:

For four balls: 1: 2^12 = 4096 (The conventional American deadness board)

For six balls: 2^30 = 1,073,741,824

For eight balls: 2^56, or more than 72,057,594,037,927,900.

Hoop clips and other accessories were produced as early as the 1860's in England, but nowhere in the world has a deadness board been known to exist before the four-ball boards were introduced in the 50's, in America. Six-ball and eight-ball deadness boards are unknown.

|

No claim will be made that the elder Swope and Swope, Jr. and the "Algonquin Round Table" croquet players invented carry-over deadness, but it's pretty clear that his group and its successors in Hollywood in the 30s shaped the development of the American game irrevocably towards carry-over deadness.

And it's just as evident by virtue of their eminence that this legendary group of players and the next generation to whom they passed along their croquet game gave USCA founder Jack Osborn not only the backing he needed to found the American association, but also the essential style and character of the kind of game he wanted to promote in America: an elegant game for the elite, a sport for the affluent class.

In the 70's, many notable players came over from England--John Solomon and Nigel Aspinall among them--to advise Jack Osborn on various elements of what would become the first "official" USCA rules, and it's easy to understand why they were were unable to persuade him to abandon sequence and carry-over deadness, the main distinguishing characteristics of USCA croquet. That's the way the game was played at the five East Coast charter clubs Osborn the politician needed to persuade to support his fledgling association. He could fiddle with other aspects of the rules--such as wiring and starting the game--but not with those fundamental elements.

|

| Everyone is dead. Nancy Hart photo. |

The isolationist culture of Backyard Croquet

When you have a croquet set and you don't belong to a club or association, what you do is play with your family and friends. And as the host (or owner of the set) your rules--or your rational "figuring out" of what the rules ought to be--become the order of the day and will perhaps persist for as long as you and yours play the game. And your friends, if they introduce the game to others, will be likely to play by those same rules.

Consider the enormous influence, then, of Herbert Bayard Swope and his glitteringly famous and influential group of friends, who played every weekend on his grounds, by his rules. When the Great Depression came to America in the 30's many of the group, including Dorothy Parker and Moss Hart, emigrated to California to play their part in the movie industry with the Hollywood set. Obviously, they would have taught the Hollywood set to play croquet their way. Those are the rules that would have found their way to the back yard of Harpo Marx and the croquet courts of Sam Goldwyn or Darryl F. Zanuck at the lavish croquet competitions they produced for the Hollywood elite and their hangers-on in Beverly Hills and Palm Springs.

In the fifties and sixties, there were highly publicized tournaments that pitted the West Coast against the East Coast, including from the West such notables as Tyrone Power, George Sanders, and Moss Hart. Who would have decreed which rules were to be used, do you think?

The toy set manufacturers regard croquet as a commodity

The lightweight and inexpensive toy sets have always been produced for quick and easy sale in retail outlets, for the most part. The manufacturers typically hire "freelance" writers to produce the "instructions for use" to be packed in those rules. Having free-lanced for a time myself, in the 70's on the West Coast, I can well imagine how the process worked: The free-lance writer would probably be given a set of rules from another manufacturer, from which to fashion a "unique" set of rules for his employer, original in the form of the presentation, if not in the substance of the rules.

In the deliberate scramble of language thus produced, it would have been easy to overlook a seemingly simple and inconsequential phrase like "after each turn." Nobody would ever notice, because at best a copy-editor from somewhere or other (maybe the owner's under-employed nephew) would correct the grammar, because faulty grammar would suggest that the manufacturers of the product weren't paying attention.

And of course, they weren't. Even if the rules were "complete and accurate," would that make a difference, considering the aforementioned culture of the casual game? I say it wouldn't, on the basis of my own experience with the casual game as well as with the craft of free-lancing instruction manuals.

|

| From the several notions we had for illustrating our cover story, we chose this one: Hans Peterson (now the president of the Sarasota Croquet) in camouflage gear, scanning the hills of Oakland in search of targets. Mike Orgill shot the photo |

As adults, Mike and I wanted something that was not only challenging but which also made sense. With the six balls of the set, we soon figured out that a two-sided, any-ball (non-sequenced) game with no carry-over deadness worked best for us, and we played it regularly until the early eighties, when we discovered the USCA. In all likelihood--referencing the broader culture of games--we may have decided that it didn't make sense to "kill" your own pieces (as one does in Parcheesi, checkers and other games)--so in our game you could hit only the opponent's balls to gain extra strokes, not one's own.

Just to show how easily a "made-up" game in the right circumstances could become the "official" game, believe me when I tell you that the Guerrilla Croquet rules described above (published as the "cover story" in Croquet Magazine) became the "official" USCA rules for backyard croquet when I wrote the first USCA website in 1996, and it remained the official game for about five years.

Similarly, when Swope returned to America after the war, he brought back not only first-rate Jaques equipment, but also the antique rules that would come to dominate American play throughout the 20th century, and eventually would be adopted as the "official rules" of the USCA with its formation in the 1970's.

Drazin discovers a telltale probable typo in an early British publication

Another of Dr. Drazin's Croquet World articles examines early rulebooks published in England, and he modestly described the gold he found in one of them this way: "As to the early origins of carry-over deadness, we may have a clue in Rule 10 of one of the deviant rule books, Rules and Regulations for Playing Field Croquet , which went through several editions from the late nineteenth century and which may have been taken up by minority groups of players throughout America.

"This rule states, 'No ball except a rover can croquet the same ball twice, until the ball has passed through an arch or hits a stake'. My guess is that the author or compositor simply omitted the words 'in each turn of play', not intentionally but inadvertently. These words recur in other rulebooks, but their significance may not have been apparent to the publishers. Croquet rulebooks of the period were a commercial commodity: it is evident that few were compiled by writers who had any understanding of the game."

These rules may have been the the source of the games James Hawkins remembers playing with his family in the 50s and 60s.

More conjectures based on equipment development

There is no record of "deadness boards" anywhere in the world until the 1950's in America. Given the complexity of remembering all the possible thousands of states of deadness in the four-ball game and the eagerness of merchandisers to sell accessories to popular games, would it not have been likely that such equipment would appear in the 19th Century, when "hoop clips" were introduced in England as early as the 1860's?

|

| This typical courtside view of American croquet demonstrates the use of the "deadness stick" that enables a seated volunteer to keep the board current, so the players (theoretically) can keep their minds on the game. Photo by Sergio Nico. |

When croquet was "restarted" in England in 1896, Walter Peel, convinced that the demise of the sport was caused by too-narrow hoops (a position Jack Osborn entertained in the early development of the US Croquet Association), decreed that the hoops should be four inches wide. Surely he would have issued similar warning about the complexity of carry-over deadness--if such a thing had existed at the time.

The probable story is now complete

Have you noticed that we now have put together all the threads needed to explain how carry-over deadness was originated and spread? Here are are the main elements of the complete story of deadness, in sequence:

- A typo in the English-published rules for "Field Croquet" around 1900.

- Herbert Bayard Swope's long stay in England, writing about the European war.

- Swope's learning of the game in England, playing by the "Field Croquet" rules.

- Swope's introduction of the game, with first-rate Jaques equipment, at his Long Island home in 1922,

- Every-weekend croquet games on Long Island, by the Algonquin Circle and many famous and influential writers and celebrities in that circle, for a couple of decades.

- The Swope deadness game adopted by the East Coast social set at various country clubs.

- The migration of the deadness game to Hollywood with several writers during the Great Depression, and its adoption by Samuel Goldwyn, Daryl Zanuck, Harpo Marx, and others.

- Widely-publicized croquet tournaments featuring celebrities and movie stars, sometimes pitting West Coast against East Coast players, in the 40's and 50's.

- Jack Osborn's discovery of the game in New York and subsequent cultivation of allies in five key groups, eventually constituting the "charter member" clubs of the USCA.

- The creation of the United States Croquet Association in 1977, with distinctive American Rules incorporating sequenced play and carry-over deadness.

If there were a footnote to this story, it might be this: Some influential USCA croquet players insist in 2018 that "backyard croquet" or nine-wicket croquet should be played ONLY with carry-over deadness, and only with four balls. Herbert Bayard Swope, Sr. would most certainly approve.

|

"CROQUET IS NOT FOR SISSIES"

Alexander Woollcott wrote to a friend an account of a remarkable croquet spectacle in 1933 at the Swope place at Sands Point on Long Island. The letter proves that the intensity of the croquet among Swope's circle lasted well into the 30's, although of the original group, affected by the Depression gripping the country, most had gone west to work in Hollywood. "I suppose you want to hear the latest Swope story," Woollcott wrote. "Burdened with Gerald Brooks as a croquet partner, he became so violent that Brooks agreed to do only what he was told and thereafter became a mute automaton, a condition which Swope enjoyed hugely. Brooks never moved his mallet or approached a ball without being told by Swope: 'Now, Brooksy, you go through this wicket. That's fine. Now you shoot down to position. Perfect!' and so on. Finally, before an enthralled audience, Swope said, 'Now you hit that ball up there on the road. That's right. Now you put your little foot on your ball and drive the other buckety-buckety off into the orchard. Perfect!' It was only then, from the shrieks of the on-lookers, that Swope discovered it was his own ball which had been driven off." Woollcott's own excessive behavior on the croquet lawn has been reported by many, including mystery writer Rex Stout, who played croquet in 1937 at Woollcott's place in Vermont. "When I roqueted Woollcott's ball into a blackberry bush," Stout wrote, "he picked up my ball and hurled it at my head from ten feet. Croquet is not for sissies." |