|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| People |

|

Archie Burchfield:

an icon of the sport

passes into history

|

|||||||

|

by Garth Eliassen, Bob Alman, and Damon Bidencope photos courtesy of Damon Bidencope and Bert Myer layout by Reuben Edwards Posted March 10, 2005 |

|

||||||

Archie Burchfield was that rare hero of American sport who always lived up to his legend. He was a tobacco farmer who lived his entire life on a farm near the tiny town of Stamping Ground, Kentucky. He was a fearsome and wily competitor, an unfailingly loyal and generous friend, and a great gentleman. After suffering from stomach cancer for more than a year, he died at his home on February 16, 2005, and was buried nearby.

It seemed tailor-made for the movies; combine the cross-class hi-jinks of the Marx Brothers in “High Society” with the triumphant come-from-behind dark horse spirit of “National Velvet”, and what have you got? It’s the Archie Burchfield story, played out on 6-wicket USCA croquet courts. And that’s half the problem. When the Archie Burchfield movie was actually being considered in the eighties, America wasn’t ready – and still isn’t ready – for any kind of a hero wielding a croquet mallet. And besides, the story wouldn’t be believable for the sophisticated movie audiences of the late 20th century. It was too much of a cliché. It couldn’t have happened like that.

|

This American icon proved, in the oft-reported words of Jack Osborn, founder and then president of the U.S. Croquet Association, that in USCA croquet, “you don’t have to be rich and from Palm Beach to be accepted.” True – but only after Archie broke through the stereotype.

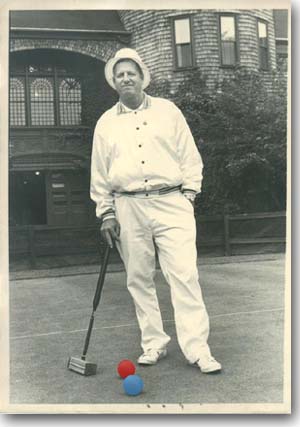

Here’s how the legend goes: In the spring of 1982, a lettuce truck rolls up to the gates of Palm Beach Polo and Country Club, and a guy with a hayseed accent in overalls pokes his head out of the window and says to the guard at the gatehouse, “I’ve come for the croquet,” and they won’t let him in – but finally they do, and he wins, beats the high society types at their own game, the first time he ever plays it. A few months later, with hardly any practice in the newly adopted game, he goes to New York and wins the National Championship with his son, also a neophyte in the game.

Pretty close, but just for the record, some facts can be corrected. Actually, it was a tractor-trailor carrying twenty-two tons of lettuce, such a big rig it couldn’t easily get through the country club gate if it tried. According to Archie (as reported in a Karen Kaplan interview in a recent issue of the USCA Croquet News), he parked across the road and walked in, and somebody directed him to Teddy Prentis, then the best-known croquet pro in the country. Teddy showed him the game, they played a couple of times, and Archie won, with the 18-inch Kentucky mallet that was his trademark in the early years of his playing career. (Later, he switched to the more conventional length, but he could always duplicate the action of the short mallet by lowering his grip on the shaft.)

Of that day, Archie told the Wall Street Journal in 1986, “We won some and we lost a few more, and I guess getting beat made me mad because I went home and told my wife I was now going to play proper croquet.”

Also present that historic day was Archie Peck, president and chief pro of the Palm Beach Croquet Club (now Director of Croquet at the National Croquet Center). Peck recalls, “When Archie finally got onto the courts, I didn’t quite know what to think about that short mallet. But then, when he bent down and hit a fast ball toward a distant wicket and it went right through, I knew instantly this guy was good. I wasn’t going to be fooled by that funny-looking mallet.”

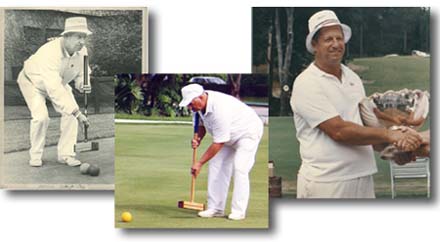

Nevertheless, four-times national champion Archie Peck was an early victim of Burchfield’s unorthodox playing style just a few months later. Just as the legend says, Burchfield and his son Mark beat Peck and Jack Osborn in the finals of the USCA National Championship in New York in September of 1982 – actually their second USCA tournament. (Archie and Mark had learned the fine points of the rules in the Southern Regional at Pinehurst in August.)

For the next decade and more, Burchfield was a force to be reckoned with in American croquet and a darling of the mainstream media who never tired of reporting the story of a country bumpkin who beat the high society dudes at their own game.

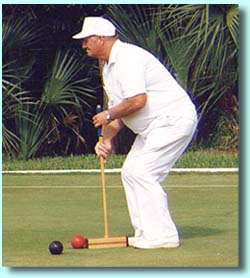

Burchfield was a master of cagey tactics in the American game

After learning the six-wicket game, Burchfield quickly became a master of its strategy. He would win games not necessarily by strong shooting but more often by cagey tactics - adjusting the positions of his balls, shooting corner-to-corner and intimidating his opponents, or simply staying behind them and waiting patiently for them to make mistakes. At a time when British-style break play was considered the only way to go, Burchfield’s tactics weren’t always appreciated; but they were usually triumphant. He competed in the early Meadowood Classics when big purses were being offered, and to this day he remains at fifth place in the National Croquet Calendar’s overall cash-prize rankings.

|

He had no doctrinaire approach to the game, but a wide-ranging appreciation of all tactical possibilities, much of it learned well on the fast clay courts of Kentucky. When Archie discovered grass USCA croquet, he already understood deadness and sequence as well as anyone in the country. (The spotty records of American croquet history show that deadness was first codified in print as part of the game in the 1935 rulebook for Kentucky Croquet.) Long breaks were a standard part of Kentucky Croquet on fast clay courts. “They didn’t play breaks until after we played them,” he said of the USCA players of the early 80’s.

Beating a path to Archie’s ranch

Archie eventually built four regulation grass championship courts on his ranch and would occasionally hold small tournaments, host foreign players such as world champion Robert Fulford, and tutor up-and-coming notables who made the pilgrimage to Stamping Ground just to play with Archie. Among them were close friend Harold Brown of Georgia (recently deceased) and Canadian champion Leo McBride.

|

| Betty Burchfield, the high-toned and much admired queen of courtside conversation, was her husband’s frequent companion on the tournament trail. (Photo by Bert Myer) |

Archie was not a wealthy man, and his ability to play in tournaments was often determined by the fortunes of the tobacco market. His wife Betty was always with him at tournaments, quietly sitting courtside and watching his games. Usually she wore Archie’s white embroidered croquet champion jacket. She reigned as queen of courtside gossip, and her good humor was greatly appreciated.

Archie’s involvement with croquet had begun in 1962, when he was introduced to Kentucky clay-court croquet behind Stamping Ground’s Christian Church. As Archie used to tell the story, the other players laughed at him the first time he played. He went back to his ranch, scraped out a court with his tractor, and began to practice. The next time he played at the church he won, and no one laughed any more.

Kentucky nine-wicket clay-court croquet is played on a 50- by 100-foot court with a diamond-shaped layout similar to backyard croquet with steel hoops firmly imbedded in concrete. At the center of the court is the “basket,” a double-wicket in the shape of a cross, dating from the earliest versions of croquet in the middle of the 19th century. Because of the speed of the balls and the finesse involved, many players use short-handle mallets as in roque, gently swinging it with one hand.

Credentials of a champion

Burchfield is a member of both the Kentucky Croquet Hall of Fame and the Croquet Foundation of America Hall of Fame. He held sixteen clay-court titles, nine as Kentucky singles champion and seven as doubles champion. In 1982 Burchfield won the Nationals Doubles Championship in New York City with his son Mark, and he and Damon Bidencope won the National Doubles Championship at Newport in 1987. Twice he won the Club Teams National Championship with Ren Kraft of Arizona.

In addition to his national titles, Archie’s other major six-wicket wins included the 1984 Central Region Championship singles and doubles with Bobby Willhoite, the 1985 Southern Regional singles and doubles with Merlin Karlock, the 1993 Midwest Regional singles and doubles with his Kentucky buddy and frequent partner Leon Parker, and the 1995 and 1996 Midwest Regional singles and doubles, also with Leon Parker.

His last major win was the Kentucky State clay-court doubles with his partner Lonnie Goodrich on Labor Day weekend, 2004.

Archie Burchfield was born September 20, 1937, the son of Archie Gray and Juanita James Burchfield Sr. He was a Kentucky Colonel, a member of the Masonic Lodge, and a congregant of the Minorsville Christian Church where he served as a Deacon. Burchfield died of stomach cancer Wednesday, February 16, at his home.

He is survived by his wife Betty; sons David Gray Burchfield and Mark Coleman Burchfield of Stamping Ground, and daughters Reba Carol Lewis of Frankfort and Shari Elizabeth Coleman of Stamping Ground. There are twelve grandchildren: Jennifer, David, Markus, Travis, Justin, and Ashley Burchfield; Jami and Jimmy Lewis; and Joy, Hope, Buddy, and Kacey Coleman.

THE ARCHIE BURCHFIELD MEMORIAL FUND

In memory of Archie and for the direct benefit of his surviving family, I invite you to contribute to the Archie Burchfield Fund. Through the generous efforts of many it is my hope that we can ease the burden of those he loved so much and that remain after Archie lost the final match that could never be won. With this fund, we may also establish a fitting permanent memorial for this icon of our game. Please send contributions to: Archie Burchfield Memorial Fund, Bidencope and Associates, 1400 Harding Place, Suite 200, Charlotte, NC 28204.