|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| People |

|

Jerry - the early years (and then some) by Jim Bast Posted June 19, 2010 |

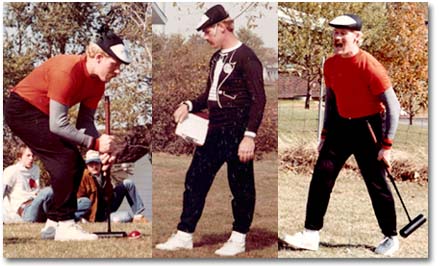

Unlike the experience of many tournament croquet players, Jerry's exposure to the game wasn't a chance encounter through a friend, or an innocent visit to a venue that featured croquet. Jerry's passion for croquet was a calling — a fait accompli.

|

| Jerry Stark |

At least that's what they called it. They did, after all, have official tee-shirts, which are now collector's items, made up each year with a different artistic motif. Some people, including the local law enforcement agencies, were convinced that the tournaments were an excuse to throw a massive party. It might have been the refrigerated beer truck with spigots on the sides that held forty or more kegs, or the flat bed trailer and generator where one or more bands played into the morning hours, or the massive bonfire that burned for days, or the hired security at the gate to the pasture.

|

These tournaments/parties were so renowned that the Hell's Angels showed up one year for a few hours. Security had mysteriously disappeared for the moment. Eventually the format developed into a circuit that included Oklahoma, Colorado, and Oregon though none of the other events ever achieved the grandeur of the Kansas City tournaments.

The rules for these tournaments allowed a player to have a caddy. The caddy's job was to carry and maintain your mallet, your beer or other recreational substance (it was the 70's), and an occasional snack, while giving you advice and lining up your shots. A good caddy was also adept at talking smack to the other players and caddies so that you didn't have to expend precious energy on this vital component of the game. Jerry and I were inseparable. The only time one didn't caddy for the other was when we were matched up in the same game.

|

Somehow, Jerry heard that there was a World Croquet Championship held annually in Parksville, British Columbia that featured a nine-hoop version of the game with three-person teams. So, for a few years Jerry and I, and four other people who varied from year to year, would make the long trip northwest to compete. The first year was a challenge because that was the year of the wicked and ill-timed Canadian beer strike. This required well-developed strategies for smuggling beer up from Washington state in order to have a proper tournament. Although this cut into their valuable croquet time the lads from Kansas City were very popular.

That first year at the tournament Jerry met a short, wiry Canadian who went by the name of Dork that had been John Wayne's Canadian fishing guide for decades. Jerry maintained his friendship with Dork for years. What impressed him was not that Dork could tell spectacular tales about fishing with the Duke; rather, that after two, three, maybe six little Molsons Dork could actually run vertically up a wall and briefly touch his stomach to the ceiling.

|

While all this was going on in the Midwest, the Arizona Croquet Club was born in Phoenix, complete with a constitution. The formation of the United States Croquet Association followed soon thereafter. In 1978, I took a job transfer and moved to Arizona. Although I still traveled occasionally to the annual Midwest tournaments I made fewer of them each year.

In late 1981, Jerry called me to report that he had read a magazine article about "real croquet" in other parts of the world and with the USCA. The article mentioned the Arizona Croquet Club and provided contact information. I called them and that week became a member of the Arizona Croquet Club. Several months later, in 1982, Jerry visited me in Arizona and there was no going back. In early 1983 Jerry called to report that he had quit his job and was moving to Phoenix. Initially, I didn't believe him. Jerry had begun to build up seniority with General Motors as a member of the United Auto Workers, at that time one of the most influential labor unions in the world, with great pay and benefits. I thought he was insane.

|

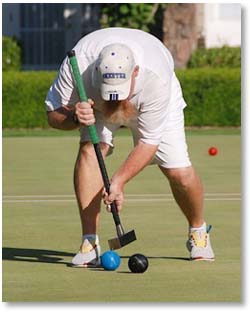

Jerry moved into my house, and his transformation into the croquet player of legend was fully underway. Jerry played every day, rain or shine, in the desert heat. He gave up his mallet making enterprise. On his first visit to Arizona he had discovered that club member Gerry Bassford was making the finest mallets money could buy at that time. Jerry's goal was perfection, and there was no point in trying to improve on a Bassford mallet. His time was better spent practicing. But he did pick Bassford's brain constantly to understand what components could be tweaked to make any mallet even better.

In a sport comprised of players who are neurotic about their equipment, Jerry was the worst I ever knew. He was always trying to find a better mallet. He would constantly hand me some new mallet he had purchased, or was thinking about purchasing, and ask me to hit with it so I could give him my impressions. It wasn't until his final mallet that he seemed to find some peace. We had both hit upon the idea for this mallet simultaneously and each ordered one. It was an Ed Roberts perimeter weighted graphite head from North Carolina, married to a graphite shaft imported from Australia. Jerry played with this mallet longer than any other he had ever owned.

|

One often hears Jerry referred to as "the gentle giant". In truth, Jerry wasn't always a giant, nor was he gentle, at least with himself in his quest for perfection. Jerry's strength and courage in the face of his cancer was not a surprise to me. I had seen it before. When we played football in high school Jerry was a wide receiver. His playing weight was somewhere around 175 pounds. He was lean, quick, and fast. The hand-eye coordination that served him so well in croquet was his greatest strength. If Jerry could touch a pass, he caught it. I never saw him drop a ball in a game or practice. He was also an unbelievably good dancer. Going out to the clubs with him was an adventure. His prowess on the dance floor made him very popular and our table was never lonely.

Not long after we graduated Jerry was diagnosed with acromegaly, a glandular disorder characterized by an enlargement of both the soft and bony parts of the extremities, thorax, and face. His was caused by a tumor on his pituitary gland. I sometimes took him in for his radiation therapy. Even thirty years later I would look for the tiny tattooed dots near his ears where the radiation probes had to be placed exactly correctly as the process of removing the tumor so near his brain went laboriously on. As he endured the months of treatments, as his body began to change, I never heard him complain. Not once.

It was during this time that Jerry told me he was afraid, something I had never heard him say before, nor did I ever hear him say it again. It was not his condition or his treatment that was making him fearful. One of the complications of acromegaly is carpel tunnel syndrome, and Jerry developed a case of CTS that was severe enough to require surgery. Jerry told me that he was afraid the surgery would not be successful and he would no longer be able to hold a croquet mallet. Later, of course, we all bore witness to his courage and determination as he did battle with cancerous moles, causing the regular removal of large amounts of flesh from his body. Again, he never complained.

|

The man was nothing if not focused. This was followed by a couple of years of now legendary conversations Jerry would have with a few trees in a small grove just off the north end of the court. Some of those trees ceased to grow during and after that period, but no croquet players were going to be in harm's way from this activity. Eventually, he settled into a routine, familiar to all of us, where he would remove himself to an isolated corner of the lawn and bully himself into getting ready for his next opportunity. I generally stayed away from him during these moments, but sometimes the old "Kansas City rules" mentality would compel me to just go over and mess with him.

|

Even during those periods when he climbed to the top of the rankings he never stopped pushing himself to be better. It is common to witness players who, after elevating their game to a certain level, become convinced that they "know it all". Even when they do ask for input about their game, which isn't often, you can tell that it is not done sincerely and that words go unheeded. Jerry was never like this. Long after he passed me in the rankings, even when I took a hiatus from serious competition for a decade, he regularly sought me out for advice and coaching. He would ask me to closely monitor his swing, or his stance. He wanted to know how I felt about certain tactical situations. He was never content to rest on his laurels.

Jerry's last test match for the USA was the Solomon Trophy at Mission Hills in December 2009, when the USA finally defeated Great Britain for the first time. I was privileged to once again play on the USA team and to be Jerry's teammate for this event. It was an emotional moment for both of us and even days later we were struggling to put our feelings into words. I had played in the very first test match against Great Britain in 1985. After the victory I managed to tell him that I had been waiting 25 years for this moment. Jerry, who had played on all six USA MacRobertson Shield teams and nine Solomon Trophy teams, replied that he had been waiting for 15 test matches. There was actually a colorful adjective placed in there that I have redacted.

|

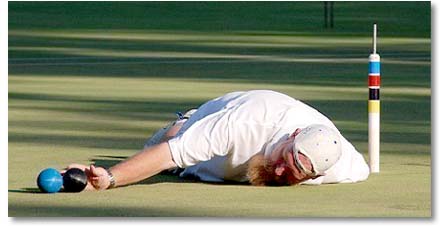

Although the cancer that would end his life already had taken hold, during the U.S. Open Jerry played a splendid tournament. It may have been the best he has ever played. In fact, Stephen Mulliner, who had stayed on after the Solomon to play in the Open, later remarked, "I am so glad that he was part of the first USA team to beat Great Britain last December and that my final game against him, during the ACA US Open immediately afterwards, was to see him win playing at or close to his best. I will remember for a long time the take-off he played from the west boundary to the east to get his rush to hoop 1. He went to 4-back, I missed and he finished with an immaculate triple." In my book, that Mulliner guy is a man of great character.

When Jerry flew to tournaments he would always book a red-eye flight if there was one available. The off hour usually meant that he could unfold his large frame into a row by himself, and he possessed a remarkable ability to sleep soundly on an airplane. I always envied him that. For closer tournaments, when he would drive, he had a habit of departing for the long drive home almost immediately after he had suffered a loss that eliminated him from contention. Although I knew full well that he was anxious to get home to Donna and Zac, I would sometimes give him grief about not sticking around to say a few more goodbyes.

|

Hey! We poked each other in the eye for nearly forty years, OK? As he walked to the parking lot that day I let my gaze linger on him until he was out of sight. Without stopping to consider the conversation we had on the way to the barbeque joint a few days earlier, I remember saying to no one in particular, "That's the last we'll see of Jerry". Man, I wish I had been wrong.

| RELATED LINKS: | |

| • | Obituary from the Santa Rosa Press Democrat |

| • | Read other tributes or post your own in Croquet World's Forum on "Remembering Jerry." |

Thanks to Adrian Wadley, Leo Nikora, Arthur Bagby, Charlie Mayo, and others for the photos