|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| The Game |

|

Painting the boundaries but keeping the string, because... |

|

by Bob Alman photos by Johnny Mitchell and Marie Sweetzer layout by Reuben Edwards Posted July 4, 2015

|

This article isn't about criticizing the rules or even proposing changes. It's about the culture of the game as it is played throughout the world. On other continents, more than 90 percent of courts use painted boundaries, while in North America, those percentages are virtually reversed, with estimates for stringed boundaries now ranging from 75 percent to 90 percent. But although the percentage of conversion from string to paint is still low, movement towards paint is now significant, sparked by newly painted boundaries on the courts of some of the largest and most prestigious croquet venues in the country--beginning with the National Croquet Center in West Palm Beach, the USCA headquarters facility.

The string bias in tradition and in the rules

Fundamentalists of the American Church of Croquet will say, quite rightly, that Jesus and USCA founder Jack Osborn never played croquet with painted boundaries, so neither should we. (Islamic fundamentalists might similarly declare that because Mohammed and his army were never observed using the drive-up window at MacDonalds to order Happy Meals to go, neither should you, or anyone, ever, or else!)

It's not just American originalists who will righteously cleave to string as "the only way," but also the entire country of Canada, without exception, and for a very good reason. Most of those clubs share with bowlers. So according to Louis Nel, even the biggest club in Canada, with four courts--Bayview, in Ontario near Toronto, which does not share with bowlers--is keeping string "in order to preserve uniformity in Canadian croquet." Also, Nel notes, "They shift their courts weekly in various directions to avoid wear patterns."

Throughout the world, in every country with a national croquet association, there are equally good reasons for retaining string boundaries at certain times and places--not necessarily because of sharing with another sport; the purchase, maintenance, and operation of even a simple system is a stretch for small clubs with their own volunteers caring for the lawns; and if the lawns are maintained by a governmental jurisdiction, getting regular boundary painting organized, managed, scheduled and coordinated with club activities could be awkward and maybe even not worth it--especially if there are no liability issues.

|

| Even in the midday heat of summer, the courts of the National Croquet Center are sometimes busy with players braving both the sun and a likelihood of thunderstorms in the afternoon. This "before" photo from the upstairs ballroom shows the lines definitely degraded as the watering of the lawn contributes to their fading. |

Nevertheless, painted lawns have been preferred everywhere for a very long time--except in North America.

|

| The "after" photo reveals refreshed white-lining, as well as the threat of more line-fading rain on the horizon. Rain or no, the typical interval between boundary paintings around the world is about two weeks. Both photos by Marie Sweetzer. |

The pros and cons extend beyond mere tradition

|

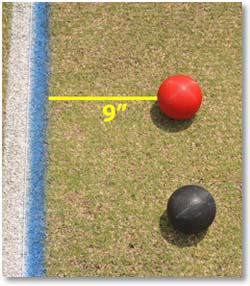

| Conversion to paint is no trivial matter when American rules are played, calling for delicate play with a 9-inch boundary margin. |

Ben can convincingly show you how getting rid of the string actually does change the game. There is no American Rules player in America whose ball has not been "saved by the string" on a boundary attack. But is that a significant factor? USCA president Johnny Mitchell, who supported the shift to paint at the NCC proposed by David McCoy and Bill Mead on the grounds of safety alone, believes all the players can adjust to paint when they are asked to. Also "I don't think that consistency relating to the boundary line is an issue. Further, we [the USCA] cannot require a venue to purchase striping machines."

|

| However, in American rules the ball is not called "out" unless more than half of it is over the boundary line, so the margin is actually almost eleven inches. The narrowness of such a call sometimes requires the judgment of a referee, but players usually find a way to agree on the precise location of that narrow line. |

| A UNIVERSE OF EASY CHOICES OF MARKERS, METHODS AND PAINTS |

|

Such a huge variety of machines and methods is now available that anyone responsible for lining courts anywhere in the world--from the smallest club to the biggest venue--can find all their major requirements satisfied in one of the machines and technologies you can find and examine on the internet. Look for exactly what fits your grounds keeping requirements at this excellent Australian website, detailing, comparing and contrasting all the factors that could possibly apply in our situation; and then search for availability and comparable pricing wherever you live.

|

Mead told me, "Until the American rules include string as an agency, it should not be allowed. We all have seen string affect the path of a ball, keeping it in play when it would have gone out of bounds.....String is an outside agency in my reading of the rules; therefore it should not be allowed to change the path of a ball."

The shift in America begins in 2012

On December 4 of 2012, Stuart Lawrence made a posting on the Nottingham Board titled "Painted lines debut in USCA national championship event." The event was the USCA Seniors and Masters National Championships, under American Rules. Lawrence noted, "In over twenty years, I had never played in a North American tournament with painted lines before this year's Selection Eights, also held at the NCC in November."

|

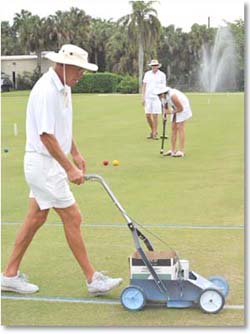

| National Croquet Center operations manager Bill Mead started making boundary lines on the 17 courts of the Center in 2012 with a four-wheeler already on the site, bought for refreshing the lines in the parking lot. |

The editor of the global, independent magazine for the sport responded on the Nottingham the same day: "Actually, the painted lines at the NCC are a MAJOR milestone, and the NCC example WILL be followed elsewhere in America. Injuries are possible with string, but not so much from painted lines...."

My posting continued, "Painted lines will be used for the NCC singles championships (also played in American rules), and my impression is that incoming American Rules tournaments (like the Palm Beach Invitational and the Beach Club) will also use choose the painted lines.

"Operations manager Bill Mead (Archie Peck's replacement) is improving his ability to paint straight lines, using a formula which apparently doesn't kill the grass. Orange painted lines are the ONLY boundary markings on the Harpo Marx lawn (the dry retention area) in the back of the NCC, permanently set up for 9-wicket croquet."

|

| The four-wheeler has the most common kind of mechanism for easily and quickly starting and stopping the release of paint. |

|

| Four times on each court, the release of paint is stopped to allow for re-aligning the four-wheeler to the 90-degree turn at the corners. |

Bill Mead, operations manager and club pro, had adapted for painting the Back Nine a four-wheel machine already in the maintenance shed which the Center had bought to refresh the parking lot lines. When Mead and David McCoy decided to thoroughly explore options for painting the regulation lawns as well, that was the machine he used, and at first, as I recall, the lines were distinctly wavey and irregular. But by the time of the fall events in 2012, they were straighter, and by now--2015--they are very straight, indeed. Mead is still using the four-wheeler, but thinks it's time to shift to the three-wheel system now more conventional for painting turf.

Conversion to paint is easier than at first imagined

The experience of Martin French of England is fairly typical. He reported a couple of years ago, "Having recently had to start doing our own white-lining after we moved our local club to a golf course, we examined the practical pros and cons of each type of machine." The club paid a couple of hundreds pounds for the machine and an estimated 20 pounds a season per lawn, with each lining lasting about two weeks. "The lines are surprisingly easy to get straight, by following a stretched cord, and if you re-mark it before it's disappeared, subsequent coats are quick and simple."

French adds that like many clubs, around the planet, "We use white lines for the full-size lawns and cord to sub-divide a lawn for coaching or novice games."

|

| Mead pushes his machine from the side to avoid stepping on the fresh paint, keeping the arrow on his machine pointed at the guide string he's put down around the court to keep the line straight. He's refreshing his white boundaries today with a thin blue line to avoid confusing the players. The best colors, he's found, are white, deep blue, and deep red. |

And yet, Hawkins notes: "One of the few big clubs in England using string is Bowdon. String does have some advantages to a groundsman. The boundaries can be extended or shrunk easily to avoid wear, and it has no chemical effect on the grass. My club in Liverpool occupies an area previously used for grass tennis courts 20 years ago. Their old boundaries still show through in the autumn; the grass is greener and more vigorous, and straight lines of worm casts appear where the service lines had been. That's the effect of chalk altering the acidity of the soil over time, and something which I'm still having to deal with.

"I've tried using chalk dust--it's extremely cheap--mixed with water. And I've tried a product used in athletics which is a mix of white paint and weed killer. It burns a permanent boundary which doesn't need refreshing. Ever. But I'm currently using the standard paint commonplace in tennis and croquet. It's largely rainproof and gives a dazzling line even from 35 yards away."

And to nail down the point, "I'm no fan of string boundaries. My ground is bumpy and my line marker has a broken wheel bodged back on with clips and bits of coat-hanger. But I can still draw a straight white paint line down the edge of a croquet lawn. For me, this is a matter of pride, marking the point where a field of grass becomes an area of sports turf. String is for initial measuring, but paint signifies permanence.

And to nail down the point, "I'm no fan of string boundaries. My ground is bumpy and my line marker has a broken wheel bodged back on with clips and bits of coat-hanger. But I can still draw a straight white paint line down the edge of a croquet lawn. For me, this is a matter of pride, marking the point where a field of grass becomes an area of sports turf. String is for initial measuring, but paint signifies permanence.

"I despair of some clubs I visit (and some of them major venues), where they paint their lines with kinks and bends. The larger the area, the more tiresome it becomes to put down lengths of guide-string, draw the lines, and then wind up balls of wet painty string. There's a temptation just to overpaint what's there, which tends to magnify any irregularities and give you a crooked line."

But, "This isn't an issue for Surbiton, with their deluxe laser-guided whiteliner. A laser is placed at the far corner of the lawn, and, no matter how erratically you walk, a sensor on the unit causes the paint applicator to hold its course. If only I could afford that sort of equipment!"

The vote for paint is equally conclusive "down under"

Both Liz Fleming of Queensland and David Ross of the Victorian Croquet Association report at least 90 percent painted boundaries in Australia. Ross emailed me that 90 percent of the clubs in all 12 regions of the Victoria Croquet Association paint their court boundaries, and that includes all twelve courts at the Victorian Croquet Center in a suburb of Melbourne. Ross found that one club still uses aluminium strips and another plastic boundary settings. And he notes, " When using the smaller 'B' courts when pressure of numbers on social days, plastic 'strings' --the kind used for clotheslines--are used to divide the full courts. With either wooden or 100 mm plastic irrigation pipes as court dividers between, there is minimal risk of tripping/falling."

The other 12-court facility, half a world away in West Palm Beach, has also switched out the PVC piping once used as ballstops in favor of lightweight irrigation pipes that yield whenever a player accidentally encounters one. For painting the boundaries at the Victoria Centre, Ross reports, "a simple marking machine developed by one of our Victorian croquet players is used, (cost A$250), and a four litre can of paint costs $16.50 and gives three markings for three courts per can."

How might the USCA official rules be changed?

Here's what the current edition of the USCA official book on rules says, in the introductory section on "standard" elements used for courts, settings, and aids.

"THE STANDARD COURT

The standard court is a rectangle, measuring 35 by 28 yards (105 by 84 feet). Its boundaries shall be marked clearly, the inside edge of the definitive border being the actual boundary. Nylon string (#18) stapled or otherwise affixed to the ground is recommended for use as the boundary lines."

Nowhere in the current USCA rules, last revised less than a decade ago, is painted boundaries mentioned. That's how much the culture has changed in just a few years. And the official rules still "recommend" string explicitly, although a demonstrably safer alternative is now available to them.

|

| Bob Van Tassel is playing Association Croquet, so he places the ball his ball on a boundary margin exactly three feet from the line. In Association Croquet, any ball that touches the line is out. |

Soon after the NCC made the switch to paint, the Beach Club followed suit, and then the 5-court PGA courts a few miles north in Palm Beach Gardens, Westhampton, on Long Island, and one increasingly influential one-lawn club also uses paint for a very good reason. Matt Griffin has turned his back-yard court in a Kansas City suburb into an activity focus for many events at his private facility, which can handle groups of up to 150 people--so he doesn't need all the income-producing traffic on his lawns bringing liability issues with them.

The same consideration might have motivated at least four of the new mostly country club venues in the mountains of Western North Carolina to choose paint, according to Jeff Soo: Sapphire Valley, Highlands, Burlingame, and Highlands Falls.

When the USCA was founded in late 70's, the only lawns available for play were adapted from "found" surfaces or from tennis courts or bowling lawns. As the association developed, in the 80s and 90s, there were more purpose-build croquet courts, but they needed to be re-configured frequently for different levels of play, especially if they were one-lawn facilities. So no one even thought of painting the croquet lawns. But now, with an abundance of multi-court croquet facilities, painted boundaries, even for USCA rules, makes more sense.

But even as painted boundaries slowly spread across the US, croquet in North America is still mostly bounded by string--and by tradition.

|

THE IDEAL THREE-WHEELER

The lawn photo supplied by Liz shows the old plastic permanent settings in the ground that most Queensland clubs have gotten rid of, along with the newly painted line to the right. Besides being entirely too permanent and immovable, the inset plastic boundaries are easily covered up with clippings and growing grass, creating a more-or-less permanent depression in the turf they mark. Aluminum or metal settings stapled to the ground are sometimes--increasingly rarely--used to mark boundaries. |