|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| The Game |

|

Croquet Genesis: how croquet clubs get their local start |

||||||||||

|

by Mike Orgill photos courtesy of Bob Alman and SFCC club members layout by Reuben Edwards

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

This article was published in 1993--maybe the height of the seven-lawn tournament and five years before this online magazine was started. When Wayne Rodoni sent me ten years of programs, I looked through them for the best of the articles we published in those volumes, which we intended to be the "ultimate" croquet program, with actual "content" in addition to flights and schedules and meal schedules. This is the best we found. It's absolutely truthful, and it represents precisely how most croquet clubs begin--with no more than tremendous enthusiasm: no equipment, no prepared surface, not even any rules. When I asked Mike Orgill whether it was okay to republish, he replied, "Yes," and " Reading it was sad. What a world we made and lost. “There will always be a SF Open,” the writer wrote. "How untrue."

In the beginning there was no croquet. The colors blue, red, black and yellow lacked special cultish significance. There were no croquet balls. There were no mallets. There were no courts, no tournaments, no handicaps, no four-ball breaks, no triple peels. There was no U.S.C.A.

There were no rule books, although the potential for rules existed, just as land and grass existed, and wood for balls and mallets existed, and steel for the wickets existed.

Then Bob Alman telephoned one gorgeous San Francisco Sunday morning and brought croquet into my world. We must play croquet, he insisted, and against my better judgment he dragged us out to Golden Gate Park, where we played ball and wicket under a grove of stately oaks. I hated it. Bob continued to nag, and we kept playing, My emotions followed the typical croquet cycle: revulsion, attraction, intense competition, obsession.

Croquet filled many sunny weekend days. Long hours of play passed in a wink, wickets were set hither and yon on hard-packed ground, on long grass, on mounds, on the sides of hills. We would have pounded them into asphalt if we could. We fell into a round of wickets made and missed, balls roqueted, arguments and exaltation. It was competition of a sort we hadn't known existed.

Croquet was an ad hoc affair. We made up the the rules, unaware that croquet of such seriousness existed beyond our merry band of eccentrics.

We played in blissful isolation. We knew that people played croquet somewhere in America because croquet sets were sold in toy stores. Croquet sets lay forgotten in dusty attics and suburban garages where people desperate for diversion found them, dusted them off and played a primitive form of croquet, using rules dredged up from half-forgotten childhood summer days But nobody played croquet as we did . Nobody but us loved croquet so utterly.

Bob Alman was the father of croquet in San Francisco. In our croquet world this was absolute truth. But Bob had an ideological blind spot. He championed croquet for the masses. There was no need for flat, protected and manicured lawns or lignum vitae mallets.

Our courts could be anywhere and any size, and our wickets could be coat hangers set in any configuration. We could play on hilltops, hillsides, swales, beside asphalt paths. We played in parks, both public and industrial, vacant lots, and sandy beaches. We dreamed of traveling to Death Valley to play on the packed salt of Badwater. Our equipment cost no more than $50 for a complete set of wickets, balls and mallets, and we could find it anywhere, from K-marts to flea markets.

We played every weekend and our skills increased. By our lights we were playing high-level croquet of a kind not foreseen by the unknown saints who invented the game. We dwelt in a blissful bubble of self-congratulation strong-arming friends to join us in daylong marathons of sublimated aggression. The world could go hang -- until an article about croquet appeared in The New York Times Sunday Magazine. Our mass-cult croquet was due for an ideological counterrevolution.

The image of croquet splashed over a two-page layout transcended everything we had created in our isolated croquet world. A full-page picture showed a white-garbed group playing something called U.S.C.A. Croquet. They held mallets with immense heads and handles that came up to their waists. The balls at their feet were as big as grapefruits and lay on grass clipped as short as a putting green. To me it seemed like nirvana.

Bob wasn't having any of it. We played the people's croquet; we didn't need any of these upper crust types.

Such was the authority of our founder's word that we let the matter slide. We went back to the parks and lots with the same enthusiasm for our rough and ready game, but the U.S.C.A. seed was planted.

We played until the fall, when I read an article about croquet in the San Francisco Chronicle. Now U.S.C.A. croquet was impossible to ignore. The article mentioned that a person named Tom McDonnell could be contacted for more information, and like an apostate, I phoned McDonnell and was converted over the telephone.

We played until the fall, when I read an article about croquet in the San Francisco Chronicle. Now U.S.C.A. croquet was impossible to ignore. The article mentioned that a person named Tom McDonnell could be contacted for more information, and like an apostate, I phoned McDonnell and was converted over the telephone.

Now the roles were reversed. I persuaded Alman to join the San Francisco Croquet Club. Together we visited Stern Grove, the home court of the SFCC.

Seeing the court for the first time I felt like a child in a room filled with over-sized toys. Everything was so huge: the balls, the mallets, the wickets, the court itself. The game was a mystery, its rules an enigma. Balls were in contact when struck, and then they weren't. There was a mysterious board with four colors describing a seemingly random pattern.

|

| Wayne Rodoni became a Championship player by defeating fellow club member Margaret Chatham on the original court of the SFCC. |

Once we joined the San Francisco Croquet Club our backyard croquet playing days were over. On finals day of the 1983 Western Regional at Stern Grove, Alman and I went across the street and set up a course on the grounds of the San Francisco Water Works. We played, Alman won, but it wasn't the same. We ended the day staring over the Stern Grove hedges at the trophy presentation ceremony like peasants with our noses pressed up against the ballroom window.

So we played the "real" game, honing our skills, such as they were.

Croquet in America was different then. There was no play as fine as you will see in the 1994 San Francisco Open. Everybody was struggling, although to us everybody else seemed so much better and unreachable.

But Alman and I had one advantage. We came into U.S.C.A. croquet with the intensely competitive experience of backyard croquet behind us. We needed no instruction or inspiration about the glories of croquet. We were rock-solid converts to that religion.

But Alman and I had one advantage. We came into U.S.C.A. croquet with the intensely competitive experience of backyard croquet behind us. We needed no instruction or inspiration about the glories of croquet. We were rock-solid converts to that religion.

Alman and I were fortunate to be present at the creation of croquet in the Bay Area. Tom and Jane McDonnell planted the seed of U.S.C.A. croquet (and by extension, world croquet) in the Bay Area. They helped bring about the establishment of both Sonoma Cutrer and Meadowood as croquet centers. The San Francisco Croquet Club would not have existed without them. The McDonnell's made the weekly trek down to Stern Grove from Santa Rosa every weekend to keep croquet's flame alive.

|

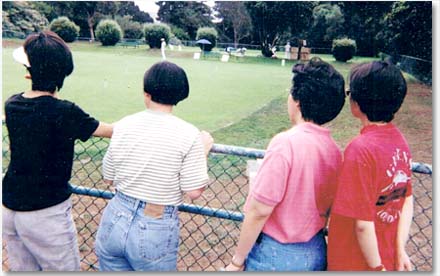

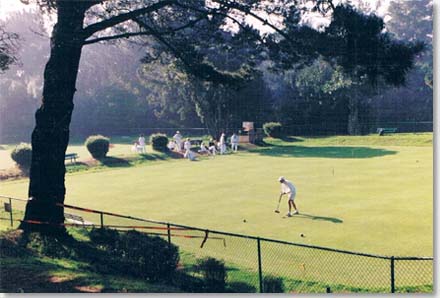

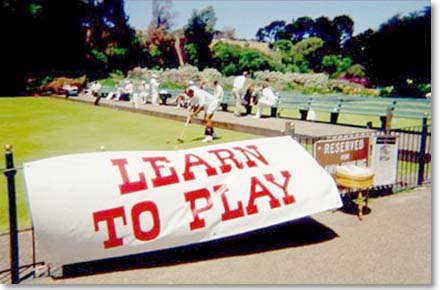

| Members often opened the gate and invited curious onlookers to come to a Saturday "Introduction to Croquet" on the lawns. |

The McDonnell's showed us that there was much more to croquet than the few people playing in the San Francisco Croquet Club. The Arizona Croquet Club, which had among its members the top players in the west, hosted a yearly tournament, the Arizona Open. Competing there in 1984 was a revelation. The tournament was played on courts better than San Francisco's, where people played croquet as if they understood what they were doing. Arizona was the home of Jim Bast, croquet's newest star, and other fine players.

The Arizonans were gruff and taciturn, like gunfighters who would reveal their martial secrets only to those who were sufficiently courageous and sufficiently skilled in hand-eye coordination But they were not unfriendly; they invited us into their homes and opened their game to us. Their tournament was run as if it were as venerable as the British Open; in our naivete we did not realize it was only two or three years old. If we had realized how unevolved everything was in American croquet our next brainstorm would have seemed less outrageous.

The Arizonans were gruff and taciturn, like gunfighters who would reveal their martial secrets only to those who were sufficiently courageous and sufficiently skilled in hand-eye coordination But they were not unfriendly; they invited us into their homes and opened their game to us. Their tournament was run as if it were as venerable as the British Open; in our naivete we did not realize it was only two or three years old. If we had realized how unevolved everything was in American croquet our next brainstorm would have seemed less outrageous.

My memory of the birth of the San Francisco Open is like all memories of important events recalled years later. A series of disconnected images serve to string together a narrative of what must have happened. I remember standing on the court at Stern Grove saying "Why can't we have our own tournament? What's stopping us?" Club members were skeptical; our club tournaments were casual affairs. How could we hope to match the organizational brilliance and connections the Arizona Club possessed?

One person ran with my idea. I remember Hans Peterson, and the white-hot enthusiasm and organizational skill he brought to the work of the first San Francisco Open. Hans and I were co-tournament directors, and he would call me many times a day with suggestions and marching orders. We gathering together a mailing list and solicited players. Paul Curtain designed the tournament logo; it is still the icon of the San Francisco Open. There were pins to order, lunches and a tournament dinner to organize, volunteers to strong-arm. We had to draw up a schedule (double elimination, of course - it was de rigueur).

One person ran with my idea. I remember Hans Peterson, and the white-hot enthusiasm and organizational skill he brought to the work of the first San Francisco Open. Hans and I were co-tournament directors, and he would call me many times a day with suggestions and marching orders. We gathering together a mailing list and solicited players. Paul Curtain designed the tournament logo; it is still the icon of the San Francisco Open. There were pins to order, lunches and a tournament dinner to organize, volunteers to strong-arm. We had to draw up a schedule (double elimination, of course - it was de rigueur).

The tournament entries were mailed to me, and for weeks I was anxious that nobody would sign up. But twenty-six players applied, more than I thought would come. And thirteen were from out of town. The first San Francisco Open was a bona fide national tournament.

|

The tournament succeeded. Miraculously, the schedule ran without a hitch. Sal Esquivel, one of our own, took first over favorites David Collins and C. B. Smith. Television and radio coverage was good for such a new event, and the publicity brought us new members.

I have a group portrait taken at the first San Francisco Open. A telescope back into time, the photograph is like those President's Cup group portraits of forgotten croquet heroes in Pritchard's History of Croquet.

|

Everybody is amazingly young. Many still play croquet. There is John Taylor, keeper of the equipment, rules expert, and natural referee; Jane McDonnell, the link to the founding of the club; Ed Breuer, now on the SFCC board of directors; Vangie Peterson, a founder of the Oakland Croquet Club; Sal Esquivel, the young Turk; Bob Alman, now SFCC president; Mike and Susan Hanner, founders of croquet in Oregon; Garth Eliassen, now the National Croquet Calendar editor; Tremaine Arkley, then at the start of an illustrious croquet career.

|

| Photographed by Mike Orgill with captions by Bob Alman, the original court of the SFCC was used for the second issue of Croquet Magazine. |

The courts of the San Francisco Open are a part of its fame--or its notoriety. The first Open had barely adequate courts, but they helped establish the tournament's legend. There were two half courts on the Sloat Boulevard lawn. One, the "hill court", featured golf holes, little hills and wicked sloping corners. The other was reasonably flat, but sloping boundaries along one side rewarded only the most desperate, and lucky, attack. These were courts they only a zero could master, and no zeroes played in the 1985 Open.

In 1986 the 19th Avenue courts were added to the Open. These old bowling lawns had been neglected, but they had good boundaries and a lot of potential. A lawn at Moscone Park in the Marina was also used that year, and in the 1987 tournament. The 19th Avenue north lawn was seeded in the same year and debuted in the 1987 tournament.The home courts of the SFCC were established, and the hill court was never used again.

|

| The view from busy Highway One above the court attracted prospective members. |

The San Francisco Open became a major tournament with the availability of the Golden Gate bowling greens in 1988. These lawns, which were laid down more than eighty years ago, are of excellent quality and have made the tournament attractive to some of the best players in the world. In 1990 all three Golden Gate bowling greens were used for the first time. This year the lawn bowling greens in Oakland will be tournament venues, making 1994 the first eight-lawn San Francisco Open.

The San Francisco Open became a major tournament with the availability of the Golden Gate bowling greens in 1988. These lawns, which were laid down more than eighty years ago, are of excellent quality and have made the tournament attractive to some of the best players in the world. In 1990 all three Golden Gate bowling greens were used for the first time. This year the lawn bowling greens in Oakland will be tournament venues, making 1994 the first eight-lawn San Francisco Open.

The players who have traveled all over the United States and the world to play in San Francisco have made the Open a major American tournament. The Open is an opportunity for players from all over the country--and the world--to face each other, to make new friends, to test new opponents.

|

| Fliers and an invitation to play were always prominent at the San Francisco Open, shown here on the fence to the bowling green we called the North Lawn. |

A tournament is measured by the players it attracts. Reid Fleming has made his mark in the Open. Arguably the best American strategist, Fleming has won the Open more than anyone else, three straight times in singles (most recently in 1989) and three straight times in doubles (with Wayne Rodoni from 1990 to 1993). Counting second and third place finishes, Fleming owns eight SFCC Open trophies.

Four foreign players have won the Open. Australia's Neil Spooner became the first by winning just after he emigrated to the United States to become director of croquet at Sonoma Cutrer.

Few who saw the final game will forget Barrie Chambers' courageous victory in 1990. The Australian triumphed despite a painful back injury and grimaced his way through the wickets on his way to victory over Wayne Rodoni. Tony Stephens, the Open's most loyal foreign supporter, turned the tables on Chambers in 1991, and there has never been a more popular Open singles champion.

Few who saw the final game will forget Barrie Chambers' courageous victory in 1990. The Australian triumphed despite a painful back injury and grimaced his way through the wickets on his way to victory over Wayne Rodoni. Tony Stephens, the Open's most loyal foreign supporter, turned the tables on Chambers in 1991, and there has never been a more popular Open singles champion.

In 1993 two titans of world croquet faced off in the final: Robert Fulford, the world's top-ranked player, and Reg Bamford. As Bamford steeled himself for a long shot someone cried, "Stop, thief!" and the spectators gave chase. Doug Grimsley and Barry Grindlesperger tackled the miscreant, and Grindlesperger (a retired L.A. policeman) applied a professional restraint. Bamford showed his aplomb when, after waiting twenty minutes for the excitement to abate, he calmly roqueted Fulford's excellent leave and went on to win the game.

| SIDEBAR BY THE EDITOR |

|

To avoid changing or adding to any of Mike's original, the editor has chosen this means to comment:

|

Last year the National Croquet Calendar ranked American tournaments in terms of competitiveness. The San Francisco Open came out on top, above the Arizona Open, above the Nationals. While the newsletter used strictly mathematical criteria in its ranking, it could also be said that the Open is at the top for another reason. It's organizers love croquet, and to show that love, they nurture croquet in a beautiful city and among uniquely interesting people.

You attend the San Francisco Open for a reunion of like souls. The tournament is a world of friends, the faces you always expect to see. And life's evanescence hits like an icy breeze when you remember that there are some, like Peyton Ballenger, that you will never see again. You remember the moments of brilliance, the crushing disappointments in your play and the play of others, the triumphs, the come-from-behinds, the fatal mistakes, the gossip, the feuds, the camaraderie, the rules disputes, the sportsmanship, the inevitable loss, the unrelenting will to win.

|

| The late C.B. Smith and the late John Taylor are obviously very pleased about something. |

One thing is certain: As long as the San Francisco Croquet Club exists there will be a San Francisco Open. As long as croquet is loved in the Bay Area, there will be people willing to work hard to ensure that the Open survives. And there will always be at least two people with short mallets and wire wickets who will keep the spark alive until the next wave of enthusiasm comes along.

Mike's prediction took a hard right, to Oakland, which has an incomparably better climate than San Francisco for "summer games," and where many champions still play on the bowling greens at Lake Merritt at the Oakland Croquet Club, which hosted the National Championship for Association Croquet in the late nineties. Reuben Edwards is now the mastermind of Bay Area croquet, and uses the two lawns of the SFCC now mostly for corporate games, which are also also done in Oakland

Mike Orgill in those ancient days partnered with Bob Alman, Hans Peterson, Wayne Rodoni, John Taylor, Ed Breuer, Karen Collingwood, Elaine Fong and others in creating and perfecting the San Francisco Croquet Club, and inventing the San Francisco Open, which was ended in the year 2000, having achieved its organizers' purpose, Alman said, after 16 years, to create "a perfect tournament." Orgill was the long-time president of the Sonoma-Cutrer Croquet Club and lives nearby with his wife Helen, having survived several big California fires. He was inducted last year into the Croquet Foundation of America's Hall of Fame.